Tai Ji Men is the living testimony that friendship can be a problem-solving tool at both domestic and international levels. A 12th-century Cistercian monk taught it already.

by Marco Respinti*

*A paper presented at the webinar “Friendship, Peace, and the Tai Ji Men Case,” co-organized by CESNUR and Human Rights Without Frontiers on July 30, 2022, United Nations International Day of Friendship.

“Friend” may well be the most uttered word ever, in all languages and throughout the whole human history. Some may object that “love” is used even more often. But in fact love and friendship are connected, and many who use the word “love” really mean “friendship.” In 2011 the BBC affirmed that the most used word internationally is the acronym “OK,” added by the American parlance to the English language. (In his recent and noteworthy book on America, journalist Federico Rampini, both a US and an Italian citizen, noted that American is a parlance of the English language). But as the BBC itself added, the acronym “OK” is less than 200 years old and cannot really compete with the historical word “friend.” Other words that may claim to be the most uttered ones by humans are “God,” “liberty,” “mum.” But “God” and “liberty” are complicated words, with different meanings and variations according to the intention of their utterers, the disposition of their audiences, the common understanding of these concepts in different societies. As for the word “mum,” statistics are difficult because it overlaps with the first wails of babies—a tender and precious detail that unfortunately invalidates any count.

You may wonder why I am indulging on these bizarre speculations, which may seem far away from today’s topic. The reason is to call your attention on the possible record as the most uttered words in history held by the words “friend” and “friendship.” They may also be the most misunderstood and abused words ever. Many who use the word “friend” do not really believe it indicates a real friendship.

A real friendship is a relationship between two or more people based on affection. While friendship is a form of love, it is different from the love that unites spouses and romantic partners, or parents and children. It is also different from the love we have for our house, country, flag, customs, or traditions. I would not venture further on statistics and try to determine which among these forms of love is more common. My point is that “friendship” is different from all of them.

Friendship implies a kinship different from romantic love or social love. Friendship is not premised on the existence of blood bonds, as in families, nor a shared past and a common destiny, as in nations. Parenthetically, the family bond also extends to adopted children. Recently, I have been told of an Italian mum and her adopted child from China. When the adopted child behaves similarly to the mother, the latter says, “Of course, it’s in your DNA.” Sometimes the adopted straight-hair girl tells her mother: “When I grow up, my hair will become curly as mum’s.” “Blood bonds” in a family are not made of hemoglobin only.

The specific kinship implied by friendship requires a supplement of sentiment. Therefore, friendship is a more difficult relationship than others. Calling someone a “friend” implies a certain amount of effort, by a voluntary act of will and reason. It implies recognizing value in another person who is not a blood relative and may not even be a citizen of our country nor belong to our culture or linguistic group. By definition, we never call “friend” a relative because this would be redundant, pleonastic, and inappropriate. A friend may be somebody whom others in our social group would regard as an enemy. And it may happen that a present friend was a former foe.

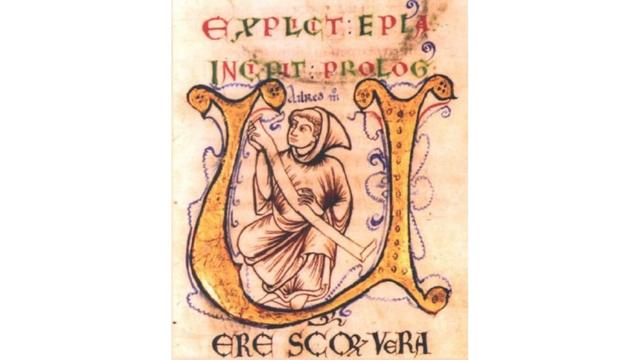

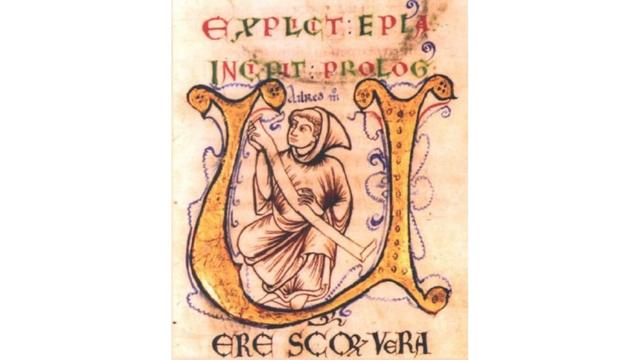

The supplement of sentiment I mentioned is well described by Aelred of Rievaulx (1110–1167), an English Cistercian monk and the abbot of Rievaulx, in North Yorkshire, England. He lived in the 12th century and both Catholics and Anglicans venerate him as a saint. He left us around 180 manuscripts. One of these is called “De spirituali amicitia,” “On Spiritual Friendship.” Probably Aelred completed it around the year 1160. The nature of this text is very peculiar. It deals with spiritual friendship, as its title plainly says. However, the tract is useful to raise a fundamental question for all human beings, of all traditions and cultures: can friendship exist without a strong spiritual bond?

Aelred answers in the negative. A Christian monk, he illustrates his topic in religious terms. For him, friendship is a form of imitation of Christ, i.e., a form of the only worthy goal in a Christian life. His argument, without diluting it, can be broadened to a general approach suitable also for non-Christians.

Aelred’s point is that friendship is sustained by spiritual kinship between two or more people. This kinship is their dedication to each other in the name of truth, sincerity, respect, and mutual help towards life’s primary goals. These goals include becoming better human beings and improving the world, together and at the same time one by one. Outside of these essential goals, there is no real friendship.

When we conceive and practice friendship in its proper meaning, we advance on the path of a global renovation. Another element in the title of today’s webinar is peace. Peace is friendship among nations. It follows the same dynamics, only on a larger scale. Just as friendship is a mutual dedication to become better persons, peace is the mutual dedication among nations, not only to avoid the horrors of war but also to build a more humane society for all. International organizations, supranational entities, and world forums often fail because they lack a soul. In other words, they lack that deep spiritual kinship that is essential to consider other fellow human beings according to their dignity and call them friends, thus avoiding war and injustice.

The third element of today’s webinar, after friendship and peace, is Tai Ji Men. Among many different cultural paths and spiritual ways, Tai Ji Men is well positioned to understand that friendship is so serious a bond that it needs not be wasted superficially. That friends are spiritual allies without whom all is lost. That friendship implies also fraternal correction, advice, and at times even bold disagreement based on moral honesty for the sake of a superior good. Tai Ji Men dizi understand what monk Aelred told us about a friendship based on the imitation of the best model one can devise in life. They understand what it means to become better human beings and to improve the world one by one and together. Our webinars and seminars are full of testimonies speaking for this simple and grand truth. The multiple international initiatives promoted by Tai Ji Men Shifu and dizi for world peace as friendship among the nations testify this all too well. They tell governments of the need of cultivating basic spiritual ties if they want to achieve true harmony and concord among their peoples.

Tai Ji Men is not only about the peaceful activity of Tai Ji Men. Tai Ji Men is also, since a quarter of a century and more, the “Tai Ji Men case.” Shifu and dizi suffered and still suffer injustice, privation, violations, violence, calumny, and tyranny. They experience un-friendship, the contrary of friendship, and peace has been denied to them for a long time. Let me then leave you with words that Aelred of Rievaulx could have said himself. “You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I say to you, love your enemies, and pray for those who persecute you.” These words are not by Aelred but by Jesus, from the Gospel of Matthew (5: 43–44.) Never let your enemies take your love away from you. Always fight for justice, as you always did and do: that is to say, with the firm calm of those who know they are right, and believe that at last justice will prevail. We are friends enough for those of you who are not Christians to accept my concluding quote of the words of Jesus.