A father of five, once rooted in Jewish Orthodox life, describes the quiet collapse of certainty that led him to AROPL.

by A. Sahara Alexander

The Ahmadi Religion of Peace and Light is one of those movements that grows in the seams of the global religious landscape, where traditional categories fail to predict who will be drawn in. Emerging from a millenarian strand of Shia Islam in the late 1990s, it has become a universalist faith, centered on the claim that its leader, Abdullah Hashem Aba Al‑Sadiq, is the promised Mahdi who will restore a Divine Just State, with members in dozens of countries and a communal headquarters in Crewe, England. “Bitter Winter” has followed its evolution in the last few years, documenting both the pressures its members face and the movement’s surprising ability to attract followers from places where one would not expect to find them.

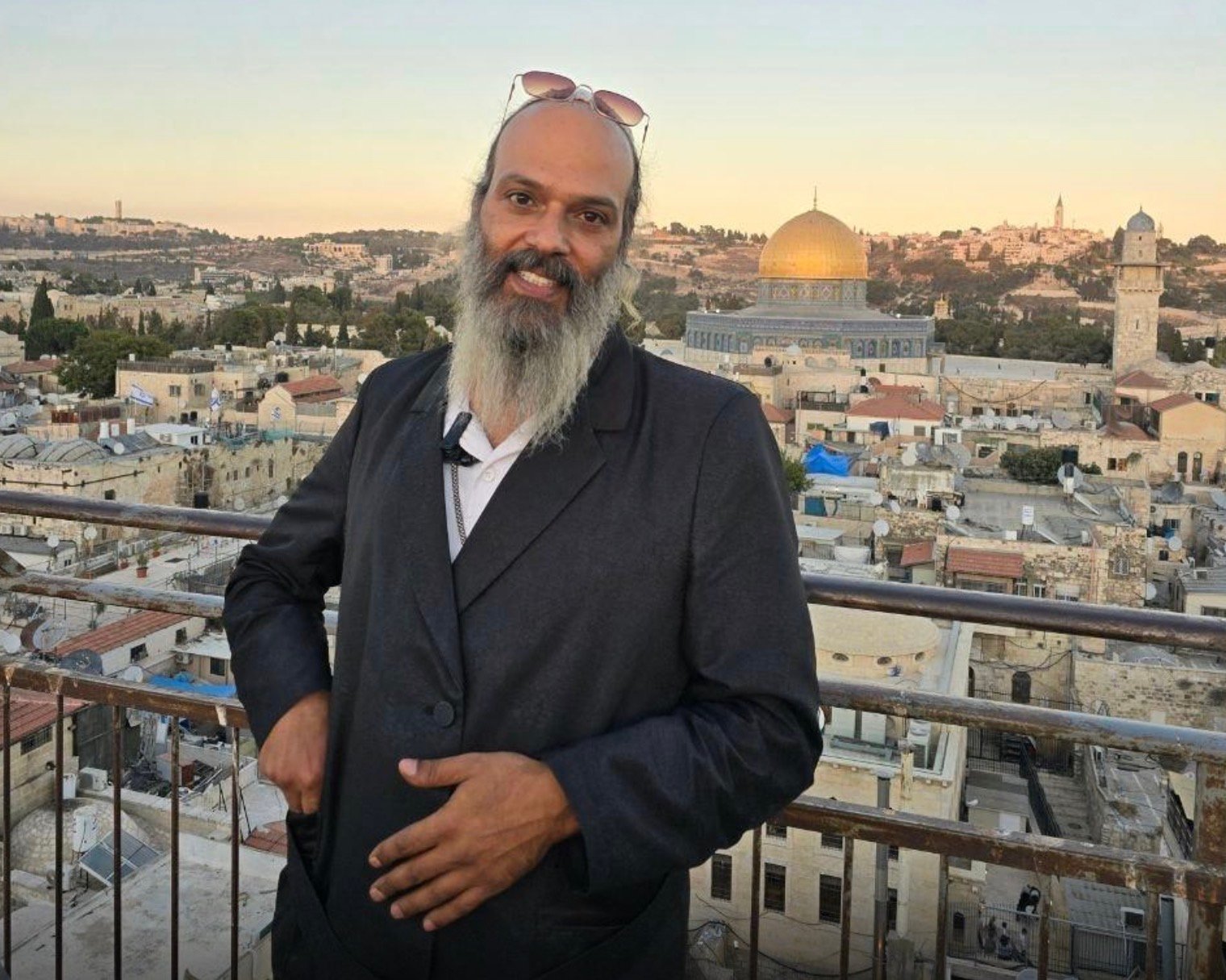

One of those places is the Orthodox Jewish world of Jerusalem, where Aharon Danin spent more than two decades living a life structured by Hasidic study and communal discipline. He spoke to us from Webb House, the AROPL centre in Crewe. When we spoke, he described a long, uneven journey from religious certainty to religious exhaustion, and then to a new conviction he did not anticipate.

Bitter Winter: For readers who don’t know you, could you start with a brief introduction?

Aharon: I’m forty‑eight, Israeli, married, a father of five. I grew up in a traditional Jewish family—my grandfather was a well‑known rabbi in the Ashdod area—and for the past twenty‑four years I lived as an Orthodox Jew. Most of that time was in Jerusalem, inside a Hasidic community. For a few years, I lived on a kibbutz, and later I trained as a mediator through the Chief Rabbinate. My life was very much inside the religious world.

BW: Did you grow up with that level of observance, or did it come later?

A: It came later. As a child, I went to religious schools and to synagogue on Shabbat, but Israel is a secular country in many ways, and by sixteen, I wanted to be like everyone else. I lived secularly for a while. After my army service, though, I felt something was missing. I didn’t have a language for it then—just a sense that the world wasn’t enough. I moved to Jerusalem, left my family home, and committed myself to Orthodox practice. I prayed three times a day, studied constantly, and tried to live as someone devoted entirely to God.

BW: What did that commitment look like in daily life?

A: I joined the Breslov Hasidic movement and became part of a community in Jerusalem. It was a very structured life. Men and women were completely separate; I didn’t speak to a woman outside my family for more than two decades. I raised money for the community, spent long hours in the synagogue, and tried to follow every detail of religious law. The idea at the heart of Hasidism is that every generation has its Moses—a spiritual guide who can lead you. I believed that deeply. I spent years looking for that figure.

BW: But at some point, the structure stopped working for you. What shifted?

A: It wasn’t a crisis in one moment. It was years of feeling that I was doing everything I was supposed to do and still not becoming the person I thought I should be. I didn’t feel closer to God. My thoughts weren’t pure, my desires didn’t disappear, and the community around me felt increasingly performative. People were acting religious, but underneath it, there was a lot of greed, a lot of pretending. I believed in my rabbi for more than twenty years, but I barely met him. Nothing moved forward. I felt stuck, and eventually I withdrew. For two years, I barely left the house. I felt broken, like there was no truth anywhere.

BW: How did you move from that withdrawal to exploring other religious ideas?

A: After the recent war in Israel, I isolated myself even more and spent a lot of time online. I started watching religious debates, lectures, and anything that might give me a sense of direction. One day, I saw a rabbi on TikTok speaking about Jesus in a neutral way—not attacking him, just discussing him. That alone was shocking. In my world, you don’t talk about Jesus. You don’t ask questions. If you do, people look at you with suspicion. So, I read the New Testament quietly. I found the teachings beautiful. I had been waiting for the Messiah since I was twenty‑four, and suddenly I was confronted with the idea that maybe he had come and been rejected. That raised questions I couldn’t ignore. Why were we never allowed to talk about this? Why couldn’t we even acknowledge the possibility of a mistake?

BW: Did that open the door to looking beyond Judaism altogether?

A: It opened the door to curiosity. I realized how little I knew about Christianity or Islam. Jews in Israel are very cut off from both. I wanted to break that wall. I prayed for guidance—not for wealth or success, just to make God happy. That was all I wanted.

BW: How did AROPL enter the picture?

A: Through YouTube, of all places. I found a channel discussing religious questions, and in one episode, a man named Abdullah Hashem Aba Al‑Sadiq was speaking. I watched one video, then another, and suddenly it was two in the morning. Something about the way he spoke—calm, logical, inclusive—drew me in. I didn’t feel attacked as a Jew. I didn’t feel pressured. I felt like someone was explaining religion in a way that made sense across traditions. In Israel, Jews and Arabs live with so much suspicion that it’s hard to imagine learning anything about Islam from a Muslim. But hearing it from him felt different. It felt new, almost like hearing a religion for the first time.

BW: What made you take the step from listening online to contacting the movement?

A: Part of it was comparison. The rabbi I followed for years never claimed to be a leader in the prophetic sense. We projected that onto him. But here was someone making a clear claim about spiritual authority. I told myself: you don’t understand everything yet, but your heart is responding. At some point, you have to follow that. Every year, as a Hasidic Jew, I would travel to Ukraine on pilgrimage. This time I decided to travel somewhere else—to meet the man I had been listening to. I contacted the movement’s outreach team. My family didn’t believe I would actually leave. But I did.

BW: What was it like arriving at Webb House in Crewe?

A: Completely unlike anything I had known. I had never had friends who weren’t Jewish. I had barely spoken to Arabs except in shops. Suddenly, I was living with Egyptians, Jordanians, Palestinians—and they treated me like family. Not metaphorically. They cared for me in ways I didn’t expect. It reminded me of the old kibbutzim, where everything was shared, except here people did it by choice, not out of ideology. It felt like a beehive—everyone working, everyone helping, not because they were told to but because they wanted to. I felt at home in a way I hadn’t for years.

Aharon later was featured on “The Mahdi Has Appeared,” AROPL’s satellite television channel broadcasting across the Arabic-speaking world. He appeared alongside a Palestinian host who is also a member of the faith, in what can reasonably be described as a historic moment: an Israeli and a Palestinian sharing the same platform on Arab satellite television, not in confrontation but in peace and coexistence.

Watching Aharon settle into AROPL makes it clear that new religious movements often grow not through dramatic revelations but through the quiet fatigue of every day. His story focuses on the search for clarity after years of feeling spiritually lost. Whether AROPL can provide that clarity to a sizeable number of non-Muslims is a question only time will answer. However, the movement’s ability to attract someone from the heart of Jerusalem’s Orthodox community to a communal house in northern England reflects the restlessness of our time. For now, Aharon expresses the relief of someone who has found a place where his questions feel accepted. This, more than any theological argument, explains why movements like this keep growing in the most surprising parts of the world.

More broadly, it is worth noting that AROPL’s public message leans heavily on the language of peace and reconciliation at a moment when global religious discourse is increasingly defined by polarization and political sorting. Whatever one makes of its theology, the movement has managed to bring together people who, in other settings, might never have exchanged a word. These encounters—fragile, limited, but undeniably real—remain unusual in today’s religious landscape, where old boundaries tend to harden rather than dissolve.

Uses a pseudonym for security reasons.