Without the Taiping Rebellion, the subsequent history of China would have been different. It also explains features of the CCP policy on religion.

by Massimo Introvigne

Part 5 of 5. Read part 1, part 2, part 3, and part 4.

On July 30, 1864, the Qing forces who had entered Nanjing learned where the Taiping Heavenly King and self-proclaimed younger brother of Jesus Christ, Hong Xiuquan (1814–1864), had been buried—in the bare ground, as his religion’s funeral customs prescribed. They exhumed the body and beheaded it. Then the remains were burned, and the ashes blasted out of a cannon.

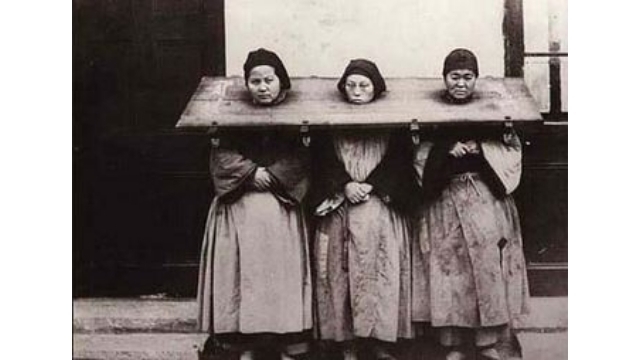

The Qing wanted to avoid any possible Taiping pilgrimage or veneration of the remains of their Heavenly King, but they did not plan to leave any Taiping alive. Tens of thousands were slaughtered, and in subsequent months and years the Hakka ethnic minority, to which Hong belonged and which had supported him, was the victim of a retaliation that approached genocide, with at least one million killed. Villages who had sided with the Taiping were burned to the ground, often with all their inhabitants.

Nobody knows how many died in the Taiping Rebellion and the massacres that followed it. The fact that historians offer a conservative estimate of 30 million and a maximum of 70 million, two very different figures, just shows how much we still do not know.

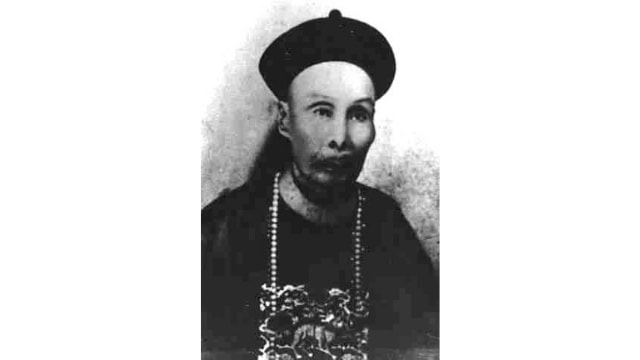

The story of the Taiping did not exactly end in 1864. In different provinces, surviving Taiping generals still fought the Qing army until 1871. Not all were killed. Some escaped to Indochina, and established small enclaves in Vietnam, Thailand, and Laos. One who had been with the Taiping as a young man, Liu Yongfu (1837–1917), valiantly fought against the French in Vietnam, then decided to help Taiwan resist the Japanese, and in 1895 became the second President of the short-lived Republic of Formosa.

While Liu’s memory is still honored in Taiwan, it is unclear whether these post-Taiping military men still believed in the Taiping religion, or were just warlords willing to fight the Qing, the Japanese, and the Westerners.

Historians have recognized that the Taiping Rebellion was a crucial event for China, and should be given much more weight in world’s history than it usually happens. Its death toll, be it 30 or 70 million or somewhere in the middle, makes it one of the deadliest religious wars, and civil wars, in human history.

It was also the beginning of the end of the Qing and of Imperial China. Although victory eventually eluded the Taiping, they had come very close to capturing Beijing and Shanghai, and would have done so without Western support for the Qing and their own internecine struggles. This proved to many that the Empire was, in Chairman Mao’s terms, a paper tiger, and overcoming it was possible. The cruelty and scale of the repression also made the Qing even more unpopular than they were before.

Without the Taiping, we can hardly understand the fall of the millennia-old Chinese Empire in 1912, and even the Communist Long March and eventual victory in the civil war. Both nationalists and Communists explicitly stated that they were inspired by the Taiping, and that the Heavenly Kingdom had proved that even ragged peasants, when motivated by a powerful ideology, can defeat a regular army.

While Chairman Mao’s assessment of the Taiping always remained positive, and he explained their ultimate defeat with lack of Marxist awareness of their own class struggle, the Heavenly Kingdom also taught him a lesson, that the mightiest empires can be defeated, or come close to defeat, when uprisings are motivated by millennial dreams.

Mao chose to downplay the religious element of the Taiping Rebellion—and inspired Kim Il-sung (1912–1994) to do the same for the Donghak Revolution in Korea (1894–95), another religious uprising interpreted by Marxists as a primitive peasant form of class struggle. But Mao was not unaware of the religious roots of the Taiping Rebellion. He saw the same revolutionary potential in a non-Christian salvationist new religion, Yiguandao, of which in the 1950s 820,000 leaders and organizers, and 13 million followers, according to official statistics, were arrested in a gigantic purge personally supervised by Chairman Mao.

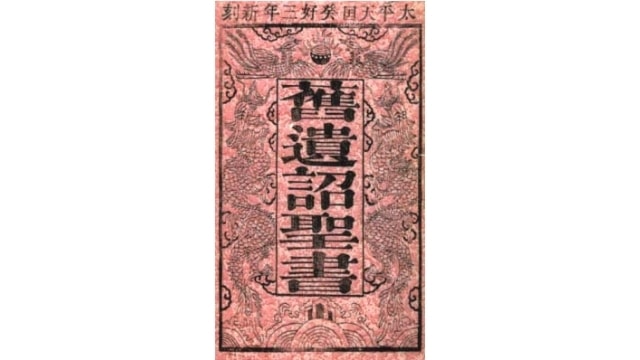

While never mentioning the Taiping when discussing “bad” religious movements, xie jiao, the CCP memorized the lesson that, if allowed to grow, millenarian Christian groups may overcome the government. This explains the CCP’s implacable persecution of The Church of Almighty God, a group which claims that its (female) leader is a divine incarnation who will usher the Millennium in.

There are still Marxist scholars who believe that the Taiping were proto-Communists, at least in the form of what British Marxist historian Eric Hosbawm (1917–2012) called “primitive rebels,” and this interpretation is mandatory in China. It is taught in school textbooks and a good dozen of museums, historical parks, and memorial halls the CCP has devoted to the Taiping in China, bracketing Hong’s peccadillos and remembering him as a revolutionary hero rather than a “cult leader.” While “cult” leaders whose sins pale in comparison with Hong’s are jailed and executed, Hong is celebrated with monuments, museums, TV series, and CCP-approved novels. It was Mao’s choice, and it was based on what he believed was Marxist orthodoxy embodied in Engels’ study of millennialist Protestant movements in early modern Germany.

However, this interpretation cannot hold. Most recent scholars of the Taiping agree it was a new religious movement, indeed the largest of the 19th century on a worldwide scale, and should be understood in religious terms. It is part of the history of millenarian movements, although with an extraordinary number of casualties (but some 100,000 Donghak victims were not a small number either, considering Korea’s size with respect to China).

In its important 2016 book Taiping Theology, historian Carl Kilcourse has argued that another interpretation we should part company with is the Christian missionary argument that the Taiping religion was not part of Christianity, but a “syncretistic” new religion. While Kilcourse also claims that Confucianism played in the Taiping experience a more important role than Hong was prepared to acknowledge, he concludes that Confucianism was used as a tool to interpret and localize Christianity.

Kilcourse criticizes “essentialist” definitions of Christianity that would exclude from the Christian field precisely its localized expressions outside (and sometimes inside) Europe and North America, which produced its most interesting developments in the last centuries.

The Taiping persuaded Chinese Evangelicals that they should distance themselves from “heretic” religious movements led by prophetic or messianic figures, lest they may be involved in their bloody repression. They did it by narrowing their definition of Christianity so to exclude the Taiping and other Christian new religions. The impulse continues to this day among Chinese Christians both in China and abroad, leading to Evangelical accusations that The Church of Almighty God and similar groups who divinize their leaders are not “really” Christian.

It all depends on how you define Christianity, but we may see this as yet another long-term consequence of the tragedy of the Taiping.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.