Hong Xiuquan, who led the Taiping Rebellion, may appear as the quintessential xie jiao leader. Yet, he was praised by Mao, and is still publicly honored in China.

by Massimo Introvigne

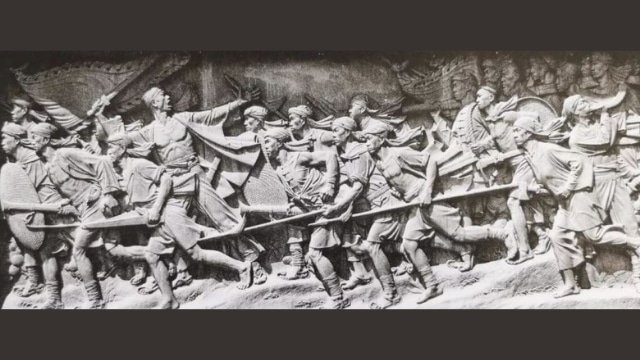

On September 30, 1949, the day before he started his 27-year term as the first Premier of Communist China, Zhou Enlai (1898–1976) led the 3,000 delegates of the First Conference of Chinese Political Consultation to Tiananmen Square, where they broke ground for the Monument to the People’s Heroes, which will become the main national monument to the revolutions of China. Ironically, in 1989, it will also become the main rallying point of students protesting for democracy.

After Zhou Enlai, at the 1949 ceremony, Mao Zedong (1893–1976) himself spoke. He described the eight bas-reliefs to be constructed for the monument, honoring eight Chinese revolutions. The second was to celebrate the Jintian Uprising of 1851, when the leader of a new religious movement called Hong Xiuquan (1814–1864) started what will become the Taiping Rebellion. Mao praised Hong as an early revolutionary leader, although he considered his revolution “unfinished.”

In the following years, Mao personally ordered to celebrate Hong and the Taiping through monuments, museums, novels, and theatrical plays, soon to be supplemented by television series.

This was, to say the least, strange. As we will see in this series of articles, Hong proclaimed himself “the younger brother of Jesus Christ,” had associates who channeled Jesus himself and God the Father, and raised an army to replace the emperor and install himself as the “Heavenly King” of China. This led to a civil war where at least 30 million, but perhaps as many at 70 million, Chinese died.

While for several years his followers were commanded to avoid sexual relations, including between husband and wives, and those caught transgressing this rule were publicly beheaded, Hong taught that the highest honor for a female follower was to sleep with him. He took eighty-eight wives, and enacted regulations on how they should serve, massage, clean, and sexually service him. In case of transgressions of these rules, no matter how small, the women were beaten. They should look cheerful and praise Hong as the blows fell. If they didn’t, or repeated the offenses, they were beheaded.

It would seem that for the Chinese rhetoric on the evil of the xie jiao, the “heterodox teachings” that the CCP presents as “evil cults,” and even for Western anti-cultists, Hong should be regarded as a stereotypical “cult leader,” almost too good to be true. Who better than Hong could serve as an example that “cult leaders” manipulate and abuse followers, particularly women, and lead them and others to their death?

Yet, none of this is happening. Hong is notable for his absence in the contemporary Chinese discourse on the xie jiao. Although Chinese students are also told that he made some mistakes, he is praised in Mao’s terms as a proto-Communist rebel who, even without the help of Marxist theory, came close to organize a national revolution in China.

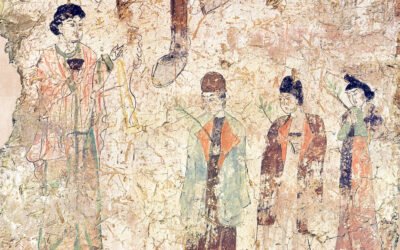

As Western scholars have noted, Mao’s appreciation for Hong and the Taiping was inspired by Friedrich Engels’ (1820–1895) analysis of the radical Anabaptists of Münster and their leader Jan Bockelson (1509–1536), who also proclaimed himself king. His antics in the German city of Münster, including the fact that he took seventeen wives while imposing a puritan moral on his followers, may indeed be compared to Hong’s. Engels and Marxist philosopher Karl Kautsky (1854–1938), who has been identified as another of Mao’s references in his assessment of Hong, dismissed tales of Bockelson’s extreme cruelty and immorality as slander produced by his opponents, and read what happened in Münster as an early Communist experiment.

Lost on Mao and Zhou Enlai was the fact that Karl Marx (1818–1883) himself had been a contemporary of the Taiping Rebellion, and had written about it, although in obscure newspaper articles that have been republished only recently. On June 14, 1853, Marx published the article “Revolution in China and Europe” in the New York Daily Tribune. There, he seemed to appreciate what he called the “peasant rebellion” of the Taiping, although in classical Marxist terms he believed that China lacked the economic pre-condition for a proletarian revolution to succeed, and such a revolution would most likely be successful in Western Europe. As scholars of Marx know, he did not regard Russia or China as particularly promising for the possibility that a Communist Party will seize the power, something he connected with the existence of a full-blown capitalist economy, found only in the West.

Marx continued to follow the information published by the Western media about the Taiping and, by 1862, he had changed his mind about the movement. On July 7, 1862, Marx published an article titled “Chinesisches” (Chinese Affairs) in Vienna’s Die Presse. Unlike in 1853, and unlike the CCP, Marx recognized that the Taiping movement had “primarily a religious character,” and compared it to Spiritualism in Europe and the United States. This time, he depicted the Taiping as cruel religious fanatics and criminals (the word “cultists” was no longer fashionable). “Doubtless the Taiping impersonates the devil in the manner in which he has been represented in Chinese phantasy, Marx concluded. But only in China was such a sort of devil possible. It is the consequence of a fossil form of social life.”

While the CCP has lionized the Taiping, as Marx did in 1853 (but no longer in 1862), as progressive, if primitive, rebels, Chinese nationalists have also assessed Hong positively, another paradox, considering that they also campaigned against “superstitious” religion and xie jiao, and continued to do so in Taiwan until at least the 1990s. Sun Yat-Sen (1866–1925), the first leader of the Kuomintang and the first president of the Republic of China, not only called the Taiping leader a “patriotic hero,” but referred to himself as “Hong Xiuquan the second,” although he also criticized the lack of democracy in Hong’s Heavenly Kingdom.

Later, Chiang Kai-Shek (1887–1975) reminisced that his grandfather has been a sympathizer, and perhaps even a member, of the Taiping, and called their rebellion “a great moment in our history,” although he was also a great admirer of the military strategies of Zeng Guofan (1811–1872), the imperial general who finally exterminated the movement. Unlike Mao, Sun and Chiang were not interested in Hong’s alleged proto-Communism, but they regarded him as a Han Chinese who had led a revolt against the “foreign” Manchu dynasty.

The mystery remains. Based on their normal assessment of “cults” and xie jiao, the CCP—and perhaps also the earlier Kuomintang in China and Taiwan—should have regarded Hong as a madman and the leader of a “destructive cult,” just as many in America regard Jim Jones (1931–1978), of the Jonestown mass suicides and homicides fame. There are no monuments to Jim Jones in the United States. There are monuments honoring Hong in China, right in the center of Tiananmen Square.

How was this possible? The Taiping Rebellion is a key event in Chinese history, which cannot be ignored by those willing to understand contemporary China. We will further explore it in the next articles of the series.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.