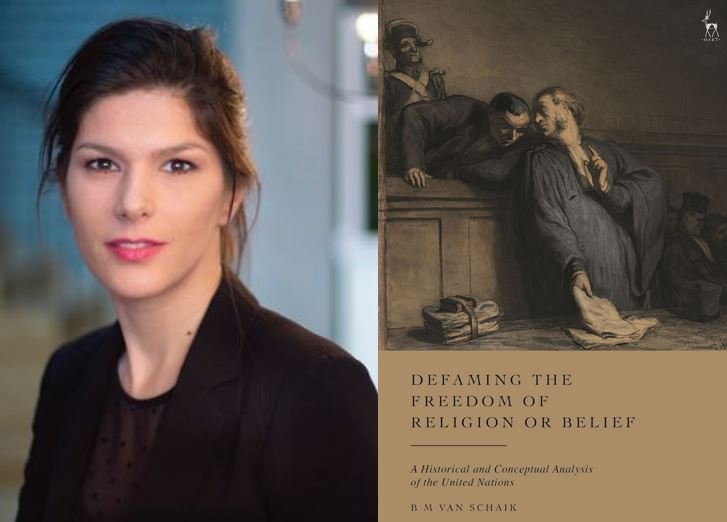

In a provocative new book, Mirjam van Schaik argues that the real problem today is not “defaming religion” but “defaming freedom of religion or belief”.

by Massimo Introvigne

In an era when the phrase “freedom of religion or belief” is invoked with both reverence and suspicion, Mirjam (BM) van Schaik’s Defaming the Freedom of Religion or Belief: A Historical and Conceptual Analysis of the United Nations (Oxford: Hart/Bloomsbury, 2025) arrives as a timely and intellectually rigorous intervention. This is not a polemic, nor a manifesto—it is a cultivated excavation of the legal, philosophical, and political sediment that has accumulated around one of the most contested rights in the international human rights canon. Van Schaik, a Dutch constitutional scholar with a flair for historical nuance, offers a work as precise as provocative.

Van Schaik opens with a deft dissection of the evolution from “tolerance” to “freedom.” Tolerance, she argues, was a virtue of restraint—an aristocratic indulgence that allowed heretics to breathe, but not to speak. It was never meant to confer dignity or equality. The shift to “freedom of religion or belief” marked a conceptual revolution: not merely the right to worship but to disbelieve. Including “or belief” is no semantic flourish—it is a legal and philosophical expansion that enfolds atheists, agnostics, and adherents of non-theistic traditions into the protective canopy of international law.

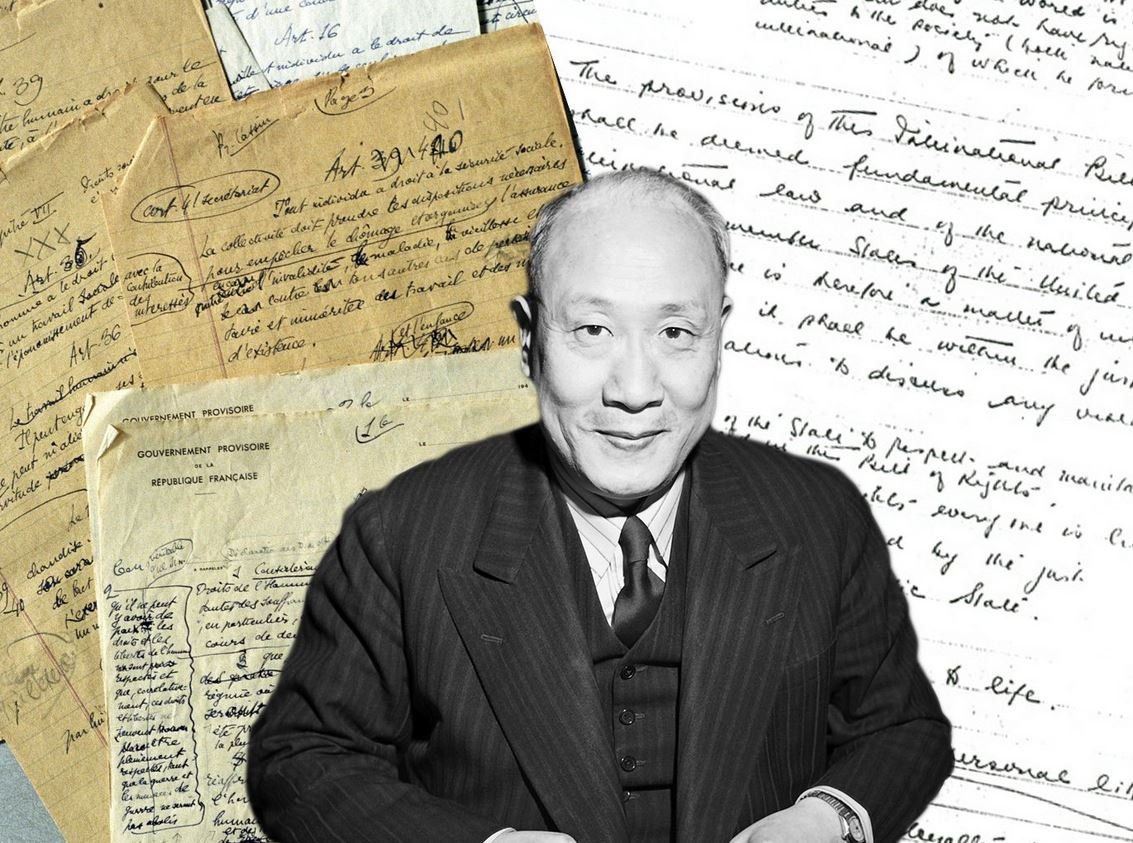

In the book’s second chapter, van Schaik reconstructs the drafting of Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights with the precision of a legal archaeologist. She challenges the notion that the UDHR is a Western imposition, noting that while Eleanor Roosevelt chaired the drafting committee, the intellectual labor was far more cosmopolitan. Chang Peng-Chun of China (later Taiwan), a Confucian scholar, played a pivotal role in broadening the scope of religious freedom. Soviet delegates, notably Aleksandr E. Bogomolov, pushed for the inclusion of atheism. Saudi Arabia’s Jamil M. Baroody, a Christian confidant of King Faisal, fought unsuccessfully to remove the right to “change” religion. This clause clashed with Saudi apostasy laws and led to the kingdom’s abstention in the final vote on December 10, 1948.

Van Schaik’s narrative is rich with detail and political texture. She reminds us that the UDHR’s universality was contested from the start, not only by cultural relativists like the American Anthropological Association but also by the Soviet bloc and states like South Africa, which feared its implications for apartheid. Yet, she argues, the final document was not a Western monolith but a mosaic of global voices.

The third chapter focuses on the legally binding counterpart of the non-binding Article 18 UDHR: Article 18 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). Here, Van Schaik highlights the subtle yet significant change from the right to “change” to the right to “have or adopt” a religion—an edit made by Baroody and backed by states cautious of Western missionary efforts. The ICCPR was adopted unanimously, but its implementation remains inconsistent. China and Cuba never ratified it; Saudi Arabia and other Islamic countries abstained, concerned that, despite Baroody’s success, the phrase “have or adopt” still implicitly included the right to change religion, an opinion shared by scholars, although not unanimously. Interestingly, Japan was among those that ratified the ICCPR but not its Optional Protocol, thus avoiding the jurisdiction of the Human Rights Committee.

Van Schaik laments the omission of the word “change,” arguing that a clear affirmation of the “right to apostasy” would have fortified the covenant’s legal and moral clarity.

In her fourth chapter, van Schaik pivots to the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), whose campaign against “defamation of religion” she views as a troubling inversion of religious liberty. Triggered by cultural flashpoints—from The Satanic Verses to the Danish cartoons—the OIC’s push culminated in UN resolutions that, despite European opposition, condemned religious defamation. Van Schaik sees this as a regression: a shift from protecting believers to protecting beliefs, with chilling implications for free expression.

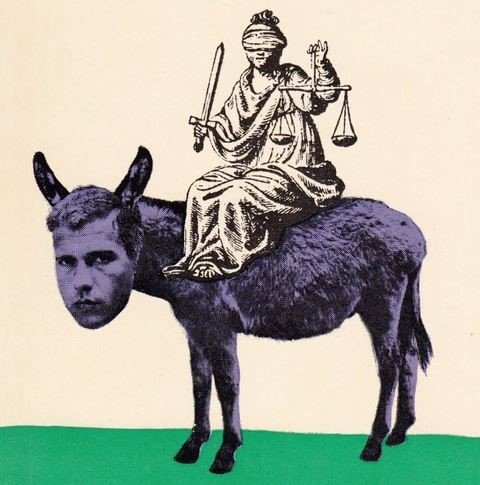

The final chapter offers a Dutch case study in secular maturity. Van Schaik recounts the abolition of blasphemy laws in the Netherlands, tracing their Cold War origins and eventual obsolescence. The 1966–68 “Donkey Trial” of writer Gerard Kornelis van het Reve, who imagined God incarnating as a donkey, is emblematic: provocative, absurd, and ultimately acquitted. Muslims, not Christians, were the last defenders of the blasphemy statutes—but they did not prevail. The laws were repealed in 2014, a move van Schaik applauds as a model for liberal democracies.

Yet here, the reviewer must interject. Van Schaik’s celebration of literary provocation is well-founded, but she skirts the thorny terrain where blasphemy bleeds into hate speech. Not all defamation is art; some is incitement. The line is thin, and Van Schaik might have drawn it more clearly.

Van Schaik’s reconstruction of the genesis of Article 18—both UDHR and ICCPR—is not merely historical but interpretive. She argues convincingly that understanding the drafting process is essential to defending the provision against contemporary distortions. Her central thesis—that “defamation of religious liberty” is more dangerous than “defamation of religion”—is compelling, especially in light of her Dutch context, where public figures have been murdered for criticizing Islam.

However, her focus on Islamic challenges to FoRB risks overlooking subtler erosions in democratic states. France, Japan, South Korea, and Argentina, for instance, engage in what Van Schaik might call “soft defamation”—distinguishing arbitrarily between “religions” and “cults,” and excluding the latter from legal protection. She rightly cites the UN Human Rights Committee’s General Comment No. 22 (1993), which prohibits such distinctions. She mentions the rights of Jehovah’s Witnesses, and—curiously, and against the prevailing opinion of courts of law and scholars—denies that Scientology is a religion, while still affirming its protection under “belief.” This is a legal tightrope, and Van Schaik walks it with grace, if not always with consistency.

While I would have included among those who “defame religious liberty” several non-Islamic and ostensibly democratic state and non-state actors, Defaming the Freedom of Religion or Belief remains a rare achievement: a book that combines legal scholarship with philosophical clarity. It is indispensable for anyone who cares about the fate of religious liberty in a world where belief is both weaponized and policed. Van Schaik has not merely written a book—she has issued a warning, and a call to intellectual arms.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.