Accusations of human trafficking are weaponized against religious minorities. It is a disturbing trend some courts are resisting.

by María Vardé

A recent acquittal in a human trafficking case has once again exposed one of the darkest aspects of Argentina’s judicial system: the use of discredited and discriminatory categories—such as “cult” or “coercive persuasion”—to criminalize religious communities under the guise of defending human rights.

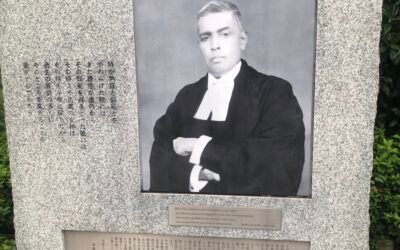

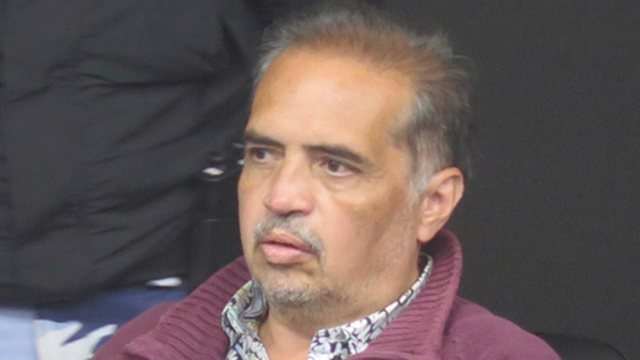

On October 13, 2025, Federal Judge Roberto Falcone, of the Federal Oral Court of Mar del Plata, acquitted evangelical pastor Roberto Tagliabué after three years of pretrial detention. He had been accused of human trafficking for labor exploitation, unlawful deprivation of liberty, and illegal medical practice, using “coercive persuasion” to manipulate the victims. In his ruling, Falcone denounced the lack of evidence and objectivity from the Public Prosecutor’s Office (MPF), pointing out that Prosecutor Laura Mazzaferri and officials from the Prosecutor’s Office for Trafficking and Exploitation of Persons (PROTEX) had constructed a narrative with no factual basis, relying on reports from the National Rescue Program (NRP) that labeled church members as “victims” without even verifying their actual circumstances.

“People came to the place seeking support, and they did so of their own free will. Vulnerability must not be confused with inability to decide,” stated the judge, emphasizing that social vulnerability or problematic drug use does not imply loss of self-determination. “To claim otherwise shows a lack of respect for those one seeks to protect. Vulnerability is not synonymous with a lack of will or inability to consent.”

Falcone also rejected the idea that the pastor’s religious message could be deemed “false,” noting that doing so would amount to “discrediting the religious beliefs of others, which, in the hands of public officials, is incompatible with the respect for freedom of worship enshrined in the National Constitution.” He was categorical in stating that a religious discourse cannot be criminalized for being different when no evidence shows that faith was used as a means of subjugation. The State, he concluded, should not label as victims those who seek spiritual assistance.

Although Falcone has shown in other rulings that he accepts the concept of “coercive persuasion,” the warnings he introduces in this ruling bring him closer to the critiques previously made by other courts in similar cases. In 2022, the Federal Court of Tres de Febrero dismissed charges against members of the movement “Cómo Vivir por Fe” (“How to Live by Faith”), the Argentine branch of the Jesus Christians, and warned of the influence of anti-cult activist Pablo Salum—linked to PROTEX—in the construction of the case. The court held that treating voluntary adherence to a minority faith and its lifestyle as a criminal act introduces a paternalistic concept dangerous to a democratic society.

In 2024, the Federal Oral Court of Paraná went even further: in the case against the International Tabernacle Church, also accused of human trafficking, it ruled that PROTEX and the NRP had committed serious abuses by coercing believers to identify themselves as victims. The ruling documented that those involved were terrorized during and after the raid and subjected to intolerable pressure to admit they had been exploited. It also recommended abandoning the term “cult” in favor of neutral designations such as “new religious movement” and emphasized the lawfulness of voluntary religious work, highlighting the total lack of evidence of trafficking.

A meta-analysis conducted in 2024 by forensic psychologist Sandra Victoria Abudi on the nine women labeled as “victims” in the Buenos Aires Yoga School case confirmed a disturbing pattern. The official report by the Technical Assistance and Forensic Investigation Directorate of the MPF (DATIP) ignored the clinical evidence and the interviewees’ own statements, imposing a narrative of generalized victimization grounded in discredited authors such as Margaret Singer. Abudi—co-author of “The Forensic Practice Manual for Psychology Professionals” (Paidós, 2021)—found DATIP’s work irregular and lacking scientific foundation, and noted that, for those women, the only traumatic event had been the state intervention itself.

The ethics and performance of PROTEX have been also questioned in other cases, where interviews conducted by dependent agencies violated basic guarantees of impartiality and non-revictimization. A ruling by Federal Criminal Oral Court No. 8 directly criticized PROTEX co-directors Marcelo Colombo and María Alejandra Mángano for their lack of gender perspective and their role in constructing a case based on induced testimonies and questionable expert reports. The ruling further noted a “discrepancy between the normative ‘ought to be’ and what actually occurred throughout the process.” In this and other cases, alleged victims rejected state assistance and expressed dissatisfaction with the procedures supposedly meant to protect them.

Academic critiques have also emerged, highlighting the paternalistic outlook of PROTEX’s leaders, which consider women as incapable of making their own decisions. This ideological framework—which equates vulnerability with moral or legal incapacity—is precisely what the courts have begun to dismantle.

Despite these judicial warnings, PROTEX has effectively expanded its mandate. Backed by extensive media and institutional dissemination under the banner of anti-trafficking efforts, the agency increasingly targets religious groups, sustains cases even when the alleged victims deny exploitation, and goes so far as to attribute unfavorable verdicts to judges’ supposed “lack of modernization.”

Moreover, while their conduct faces severe criticism from an increasing number of oral courts, Mazzaferri, Colombo, and other PROTEX agents continue to actively promote training sessions on “coercive organizations” and “cults” at universities and public institutions. The situation has become paradoxical: those lecturing on human rights are the same officials accused of violating them in the exercise of their duties. The contrast is striking—what the courts reject as discriminatory and unlawful reappears as institutional “training” and official communication.

The concept of “coercive persuasion,” de facto turned into a procedural dogma, is nothing other than the old, already discredited “brainwashing” theory promoted by anti-cult activism. Its adoption by PROTEX and by rescue and victim-assistance agencies reveals the institutional penetration of a discourse that pathologizes faith and turns spiritual dissent into a crime. In practice, the Argentine State has assumed the power to decide which beliefs are “reasonable,” who may teach spirituality, and who must be “rescued” from their own spiritual practice.

The result is the systematic creation of “involuntary victims”—people whose autonomy is denied in the name of their protection—and “cult leaders”: religious or community figures persecuted for promoting non-hegemonic ways of life.

These proceedings violate fundamental rights: freedom of religion, equality before the law, the presumption of innocence, and the right not to be subjected to institutional coercion. In the name of fighting human trafficking, acts of symbolic and material violence have been committed: raids, unfounded arrests, confiscations of property, and, above all, the destruction of legitimate communities.

The anti-cult crusade in Argentina can no longer be presented as a humanitarian policy; it is an institutional doctrine that, even as it is criticized in the courts, reproduces itself through official “training” programs—violating the very freedoms it claims to defend.

Maria Vardé graduated in Anthropological Sciences at the University of Buenos Aires and is currently a researcher at the Instituto de Ciencias Antropológicas, Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad de Buenos Aires (Institute of Anthropological Sciences, Faculty of Philosophy and Humanities, University of Buenos Aires). She has written and lectured on archeology, spirituality, and freedom of religion or belief.