Judicial Day embodies the very meaning of democracy. Why, then, does Taiwan choose to erode democracy on a global scale by persisting in its unfair treatment of Tai Ji Men?

by Marco Respinti*

*A paper presented at the 2026 Judicial Day Forum, “State Obligations under the Two International Human Rights Covenants—Taking the Tai Ji Men Fabricated Case as an Example,” National Taiwan University, Taipei, January 11, 2026.

The anniversary, celebrated every year on January 11 by the Republic of China since 1943, stands as a marker of civilization. Known as Judicial Day, it commemorates the moment when the ROC, through the abolition of the privileges granted to citizens of the United States and the United Kingdom in China under the so‑called Unequal Treaties, entered an era of legal clarity. In essence, the ROC reduced to a minimum—approaching zero—the possibility that arbitrary power could trample upon the inalienable rights of its citizens, thereby establishing “[…] a system based on the principles of justice, equality, and the protection of individual rights. It is a day to celebrate the resilience of the Taiwanese people in their pursuit of a legal system that reflects their values and aspirations.”

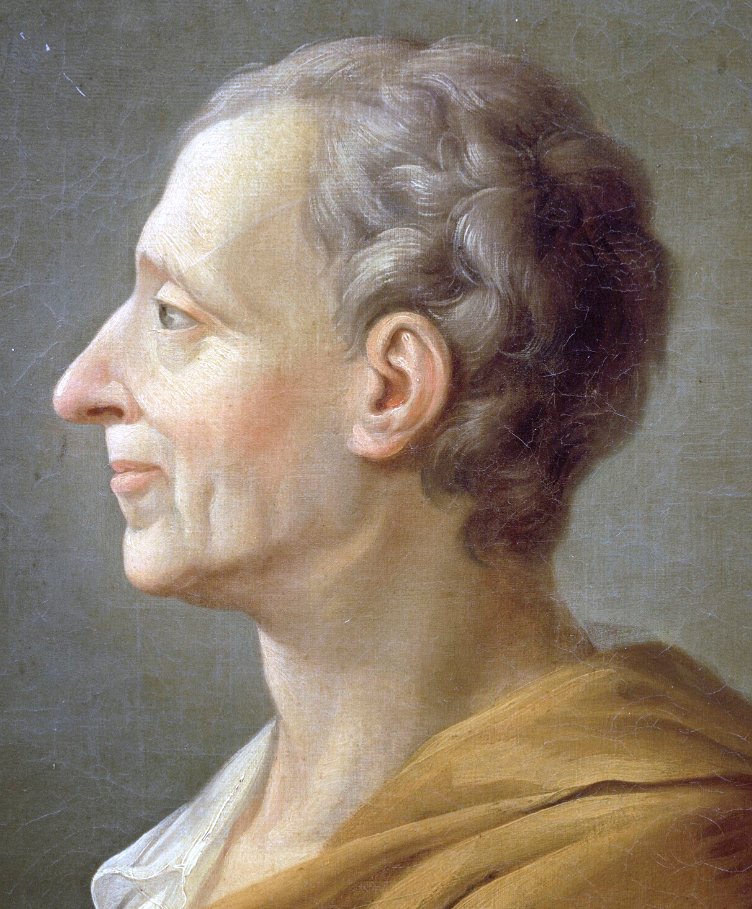

This major achievement, visible before the eyes of the world and of history, is not without precedent. It recalls the long efforts undertaken by humanity across the centuries to secure justice beyond despotism and equality before the law. Scholars have documented this fundamental struggle, beginning with the Babylonian king Hammurabi in the eighteenth century BC; continuing through Ancient Greece in the fifth and fourth centuries BC and the Roman classical period; extending throughout the European Middle Ages; and receiving decisive codification in England in 1215 with the “Magna Carta,” followed by further intellectual elaboration in 1748 by Charles‑Louis de Secondat, baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (1689–1755), author of “De l’esprit des lois,” in English “The Spirit of the Laws.”

This long history of attempts and struggles—marked by failures and renewals alike—illustrates the substance of a concept that is the very name of justice: the rule of law. Although this is a modern expression in English, its essence is universal and enduring, valid under every sun and rooted in the very core of humanity’s understanding of good governance, which human beings, despite their flaws and sins, have always held dear as a defining mark of true civilization. Whatever name the concept of the rule of law has been given—defined and articulated across different times, places, and civilizations—its meaning remains unchanged. The English expression that has come to serve as its universal designation, “the rule of law,” in fact says it all.

At its heart lies a basic, uncompromising, and inviolable affirmation: that human beings are not to be governed by other human beings and their will or whims, nor by erratic powers, unpredictable force, or arbitrary might, but by objective, clear, intelligible, and, above all, just norms. It is the law that makes kings, not the reverse; and it is obedience to the law—by both governors and governed—that grants legitimacy to governments and rights to the people. In short, this idea is noble and enduring precisely because it represents the secular echo of a divine commandment. Justice is not what human beings decree it to be, but reverent adherence to a pre‑human, transcendent criterion that distinguishes good from evil.

All societies that, at the very least, strive to recognize this principle within their norms of coexistence and make sustained efforts to overcome arbitrariness through equity are genuinely inspired by a profound sense of justice that honors humanity. The ROC chose to walk this path eighty‑three years ago, and it should never forget that choice. For this reason, every step backward along this path is a step backward for civility and civilization itself. Any failure in this domain harms not only Taiwanese society—which would already be grave enough—but the entire world. When, and if, the ROC or any part of its institutional apparatus fails to uphold the rule of law, whether in overt or more veiled forms, it is not only Taiwan that falters; humanity as a whole does. If the ROC does not treat its citizens fairly, equally, and justly, a step backward toward barbarism is taken.

The ROC must therefore honor the rule of law, in the name of all humanity, at every moment of its political life and under all circumstances. This obligation includes the case of Tai Ji Men, a menpai (similar to a school) of qigong, self‑cultivation, and martial arts rooted in esoteric Taoism, which has instead seen its fundamental rights curtailed since 1996. What humanity honors most in the rule of law, whatever name this concept may bear, is its spirit of integrity, accountability, independence, transparency, openness, accessibility, legal certainty, and protection—qualities that are instinctively and universally evoked whenever we invoke and cherish the words “democracy” and “social justice.” It follows that any breach in the rule of law and in its effective implementation in any state of the world constitutes a diminution of democracy. Consequently, any such breach within the ROC diminishes democracy not only in Taiwan itself, but in the world at large.

The drama of democracy diminished in the unresolved case of Tai Ji Men—after all levels of the Taiwanese judiciary, including the Supreme Court, upheld the rule of law by unequivocally clearing the movement of all false, and even fabricated, accusations—remains a stain on the noble and admirable country of Taiwan. It is a stain strictly, exquisitely, and exclusively political in nature. It should therefore be resolved at the political level as soon as possible. What is at stake is full democracy and the profound significance of Judicial Day. The world is once again waiting for the Republic of China to live up to its noble spirit and embody the high‑mindedness it demonstrated to all humanity eighty‑three years ago, when it chose to stand on the right side of history.

Marco Respinti is an Italian professional journalist, member of the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), author, translator, and lecturer. He has contributed and contributes to several journals and magazines both in print and online, both in Italy and abroad. Author of books and chapter in books, he has translated and/or edited works by, among others, Edmund Burke, Charles Dickens, T.S. Eliot, Russell Kirk, J.R.R. Tolkien, Régine Pernoud and Gustave Thibon. A Senior fellow at the Russell Kirk Center for Cultural Renewal (a non-partisan, non-profit U.S. educational organization based in Mecosta, Michigan), he is also a founding member as well as a member of the Advisory Council of the Center for European Renewal (a non-profit, non-partisan pan-European educational organization based in The Hague, The Netherlands). A member of the Advisory Council of the European Federation for Freedom of Belief, in December 2022, the Universal Peace Federation bestowed on him, among others, the title of Ambassador of Peace. From February 2018 to December 2022, he has been the Editor-in-Chief of International Family News. He serves as Director-in-Charge of the academic publication The Journal of CESNUR and Bitter Winter: A Magazine on Religious Liberty and Human Rights.