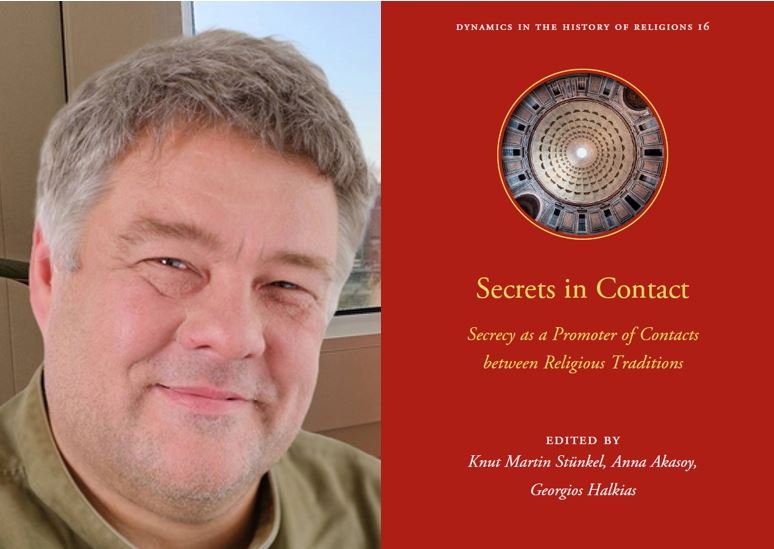

A welcome antidote to modern “secretophobia,” even if its final chapter stumbles into the very polemics the rest of the book transcends.

by Massimo Introvigne

“Secrets in Contact: Secrecy as a Promoter of Contacts between Religious Traditions,” edited by Knut Martin Stünkel, Anna Akasoy, and Georgios Halkias (Leiden: Brill, 2026), is a notable academic volume that challenges a pervasive yet often unexamined prejudice. For years, both public discourse and scholarship have been influenced by what Rosita Šorytė has termed “secretophobia”: the reflexive suspicion that secrecy in religion is inherently sinister, serving as a veil for abuse, manipulation, or separatism. In contrast, this book demonstrates that secrets do not merely divide; they also connect, travel, translate, and create bridges between traditions.

The editors open the volume on a methodological note. In the introduction, Philipp Reichling and Knut Martin Stünkel argue that studying secrecy means accepting an “epistemological and ethical double-bind”: one must analyze what is, by definition, hidden. They distinguish between “mystery”—that which is essentially unknowable—and “secret”—that which is not known to most people. This distinction allows them to propose a taxonomy of how secrets function within and between religious communities. Against the sociological orthodoxy shaped by Georg Simmel, who saw secrecy primarily as a tool of boundary-making, they show that secrets can also serve as interfaces, points of contact, and even invitations. Their example of the ecumenical and esoteric circle at the Franconian court of Sulzbach is emblematic: secrecy did not isolate that community; it united it.

In the first chapter, Knut Martin Stünkel examines the concept of the “blank space,” describing a secret as a frame without an image—a non-determined space that invites interpretation. In the “Gospel of Thomas,” the “secret sayings” of Jesus are recorded, yet still require interpretation; the secret lies not in hidden content but in the challenge of perceiving the obvious. Herodotus similarly employs a language of secrecy, leaving things unspoken, to foster familiarity between Greek and Egyptian religious worlds. Here, secrecy functions as a communicative strategy, providing a space where different traditions can project their meanings onto one another.

Chapter 2, authored by Beate Ego, addresses the Hekhalot literature of early Jewish mysticism, in which secrecy operates not only as a literary device but also as a spiritual technology. The ascent through the divine throne halls necessitates ethical purity and mastery of powerful names. Scholars such as Leopold Zunz and Peter Schäfer have observed the tension between esotericism and exotericism in these texts: the divine form remains hidden, the holy name is described as a “great secret,” yet the hidden Torah is intended for all Israel. In this context, secrecy serves both to elevate mystics above ordinary rabbis and to offer consolation to a suffering community through the promise of divine intimacy.

The theme of contact is explicitly addressed in Peter Wick’s chapter, which examines Jewish and Christian interactions with Hellenistic mystery cults. Wick demonstrates that early Judaism and Christianity did not oppose the mysteries but instead selectively incorporated elements from them. Paul’s theology of participation in Christ’s death and resurrection parallels mystery cult initiation, and Mark’s Gospel employs “mysterion” to signify an unspeakable revelation accessible only to insiders. Early Christianity, therefore, was integrated into a complex network of ritual and symbolic exchange.

In chapter 4, Kathy Ehrensperger provides a nuanced analysis of Paul’s use of “mysterion” in Romans 11. Paul employs the term not to conceal content but to address the arrogance of gentile Christ-followers. The “mysterion” functions as a tool for inclusion, emphasizing that God’s mercy extends to all Israel, regardless of their status “in Christ.” However, the “blank space” Paul leaves—specifically, the question of how “all Israel will be saved”—subsequently became a focal point for exclusionary Christian interpretations. Thus, a secret intended to foster unity was later reinterpreted as a source of division.

Chapter 5, authored by Jan Heilmann, extends the exploration of blank spaces by examining the history of the Eucharist. Early Christian communal meals were similar to Greco-Roman banquets and only later evolved into stylized morning rituals. Paul presents the meal as a placeholder for Christ’s absence, whereas John Chrysostom uses “mysterion” to signify Christ’s presence. According to Heilmann, the process of rendering the Eucharist secretive was not a withdrawal from contact but rather a result of interreligious exchange with mystery cults.

The volume subsequently shifts its focus to Asia. Henrik H. Sørensen’s chapter on Daoism and Esoteric Buddhism offers a comprehensive comparative analysis. In East Asia, secrecy, mystery, and magic frequently intersect; the “three mysteries” of Esoteric Buddhism—mind, speech, and body—were adopted by Daoists, who also incorporated the Buddhist reverence for Sanskrit as a divine language. Sørensen demonstrates how secrecy in sound, space, association, action, and scripture contributed to the development of a shared ritual vocabulary between the two traditions. Rather than isolating them, secrecy facilitated mutual appropriation.

This theme is further developed in Friederike Assandri’s chapter on early medieval China, where the Daoist concept of “xuan” (“dark,” “mysterious”) became a shared epistemological space with Buddhism. Buddhist figures such as Zhi Dun and Kumārajīva employed “xuan” to articulate “prajñā,” while Daoists adopted Madhyamaka logic to interpret the “Daode jing.” This interaction resulted in both mutual enrichment and intense competition. In this context, secrecy functioned not as a barrier but as a contested space—a shared mystery upon which each tradition projected its claims.

![Ren Yi (1840–1896), “The Monk Zhidun [314–366] Admiring a Horse.” Credits.](https://bitterwinter.org/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Secrets-3.jpg)

The volume then addresses contemporary contexts. Jens Kreinath’s chapter on Alawite secrecy in Antakya, Türkiye, exemplifies anthropological nuance. Kreinath distinguishes between “concealment” (kitmān) and “dissimulation” (taqiyya), demonstrating how Alawites employ secrecy to preserve identity while promoting interreligious coexistence, particularly with Orthodox Christians. Their secret prayer, transmitted orally, fosters spiritual kinship, while public discretion enables integration into the broader social fabric. Secrecy thus becomes a double-bind: visible to insiders, invisible to outsiders, and essential for survival.

Anna Akasoy’s chapter on Islamophobia and imagined secrecy is one of the book’s most potent. She analyzes how post‑9/11 cultural productions—from Jonathan Horowitz’s installation “19 Suspects” to novels like Amy Waldman’s “The Submission” and Mohsin Hamid’s “The Reluctant Fundamentalist”—construct Muslims as bearers of hidden motives. Here, secrecy is not absolute but projected, a blank space filled by fear. The accusation of taqiyya becomes a trap: an imagined secret that can never be disproven. Akasoy shows how literature and film can counter this dynamic by inviting empathy and exposing the mechanisms of mistrust.

In chapter 10, Daniel Beben investigates the Ismāʿīlīs of Central Asia, whose centuries-long practice of taqiyya resulted in psychological strain. Their response involved the creation of imaginative narratives, such as the “Four Pillars,” which recast prominent Sufi saints as secret Ismāʿīlīs and established an imagined brotherhood of hidden believers. This strategy enabled Ismāʿīlīs to navigate Sunni environments while maintaining their identity. In this context, secrecy functions not as dissimulation but as re-enchantment, providing a means of envisioning a world populated with allies.

Chapter 11, authored by Hildegard Piegeler, presents an abrasive critique of esotericism and its scholars, from the “imaginary tradition” of “hautes sciences” in pre-revolutionary France to modern occultism and Blavatsky’s Theosophy. Piegeler argues that contemporary scholarship on esotericism risks becoming apologetic. She singles out Antoine Faivre, whom she calls a “theologian of esotericism,” Kocku von Stuckrad, and Monika Neugebauer-Wölk as scholars who have tried to immunize esotericism, which she sees as an irrationalist and reactionary project aimed at substituting “belief” (of the worst form) to scientific “knowledge” with the complicity of academic apologists. She is persuaded that “The boundaries between belief, in the sense of assuming the truth of something, and knowledge are much more clear-cut than the scholars that have assembled in the ‘European Society for the study of Western Esotericism’ since 2005 would like to insinuate.”

The tone of this chapter diverges from the rest of the volume, which generally explores secrecy as a dynamic, relational, and productive force. Piegeler’s essay adopts an unnecessary, militant, and polemical stance toward esotericism and its scholars (in itself perhaps a form of “belief”), in contrast to earlier chapters that highlight the generative aspects of secrecy. Nevertheless, as only one of eleven chapters, it does not diminish the volume’s strength.

Overall, and notwithstanding the unfortunate inclusion of Piegeler’s chapter, “Secrets in Contact” serves as a persuasive response to “secretophobia.” The volume demonstrates that secrecy is not inherently pathological but rather a human strategy that can be protective, playful, or transformative. While secrets can create divisions, they also have the capacity to connect traditions, generate shared vocabularies, and establish imaginative spaces for interreligious engagement. While today secrecy is frequently associated with danger, this book underscores that the hidden can also function as a site of encounter.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.