Since 2020, Tai Ji Men has been barred from their sacred land with arbitrary rulings. What significance does this seized, unattended land show for scholars of religion?

by Márk Nemes*

*A paper presented at the webinar “Entering the 30th Year of the Tai Ji Men Human Rights Case,” co-organized by CESNUR and Human Rights Without Frontiers on December 10, 2025, UN Human Rights Day, and in preparation for entering the 30th year of the Tai Ji Men case.

This paper highlights an aspect of the Tai Ji Men Case that, so far, has been under-researched and underexposed, besides the elements most of us are already well acquainted with.

We all know of the 1996 state crackdowns on many spiritual minorities of Taiwan, including Tai Ji Men. We are aware that the accused were later exonerated of all charges by the Taiwanese Supreme Court in 2007. We are also aware that the Supreme Court explicitly stated that there was no basis for the claims of tax evasion and that the gifting practice known as “red envelopes” should be considered non-taxable gifts. At the same time, we are familiar with the ulterior activity of the Taiwanese National Taxation Bureau, which issued tax bills for the years between 1991 and 1996, before the conclusion of the broader legal procedure. Although these bills were challenged in court alongside the criminal case, this legal situation created a technical loophole that eventually led to the Administrative Court’s 2006 decision against Tai Ji Men, before the Supreme Court’s Criminal Division issued its conclusive verdict. Even though the Criminal Division cleared Tai Ji Men of all charges, the Administrative Court’s 2006 verdict remained in effect, unamended. Based on this procedural technicality, tax authorities, while agreeing to correct the bills to zero for all other contested years, enforced an unjust bill for 1992. Thus, in 2020, they seized, unsuccessfully auctioned off, and then nationalized 50 plots of sacred land and bamboo forest belonging to Tai Ji Men. These plots were intended for a self-cultivation and educational facility and were planned to serve as a spiritual center for the movement in Taiwan.

As a scholar of religion, I am not particularly well-versed in legal matters, and my opinion on this matter should not be considered authoritative. Nevertheless, in matters of religious and spiritual practice, I do have a doctoral degree, which gives my opinion some weight. I have taken up this vocation with the intention of identifying observable parallels across diverse cultural environments with the aim of shedding light on human nature itself. As such, in reviewing the Tai Ji Men Case for this seminar, I have encountered a novel possibility that could be of interest to scholars of religion as well. My idea was to test whether the seized sacred land of Tai Ji Men could be considered a cross-cultural parallel to classical antiquity’s “temenoi”—sacred groves dedicated to worship, sacrifice, and mystical experiences. In classical antiquity, these sacred groves were spheres where spiritual advancement, communion with transcendent beings, and higher consciousness could be achieved. The term’s name derives from the Greek words “temno” or “temnein,” meaning “to cut” or “to separate.” It refers to the act of cutting something out of the mundane world and land, separating it from the profane, and creating taboos by outlining something that should be considered untouchable and unchangeable, as its power precedes even those who found it.

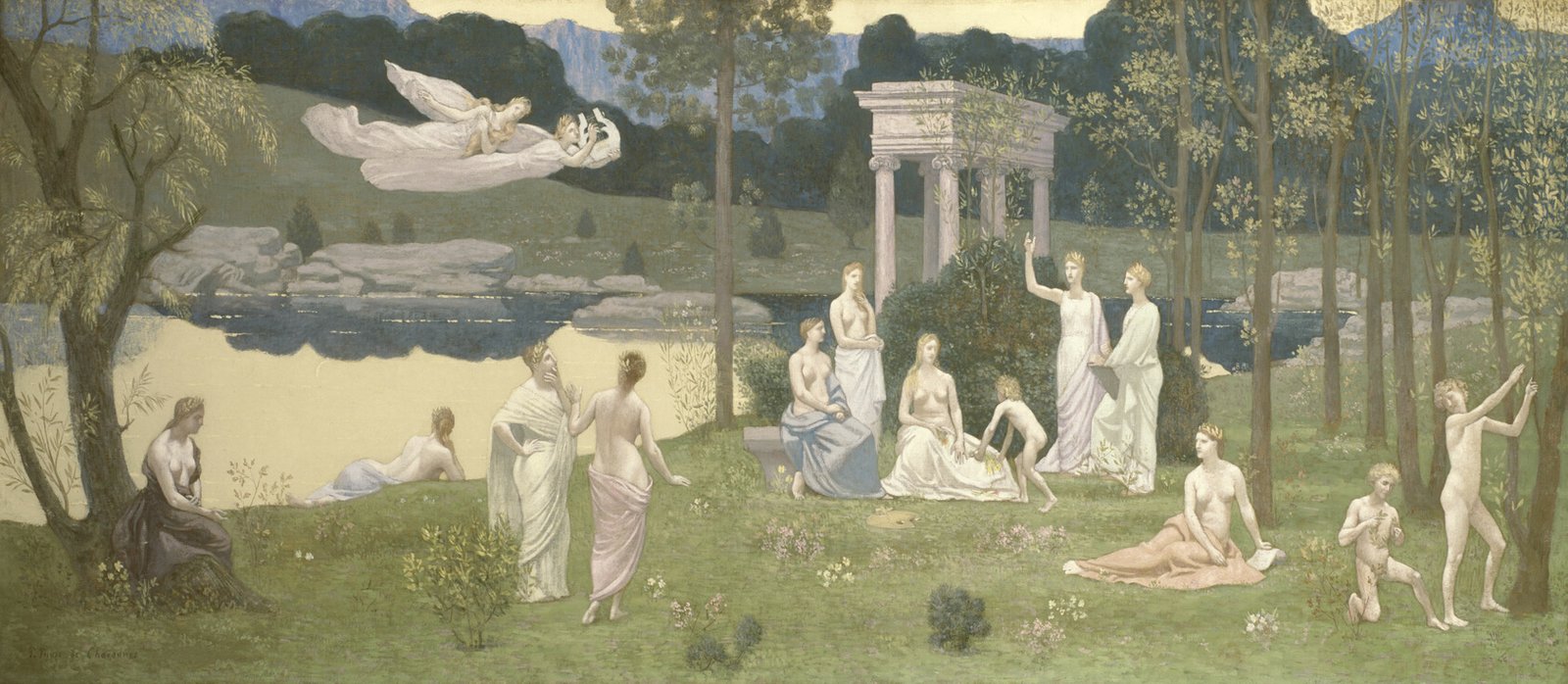

“Temenoi” served as enclosed spaces reserved for the gods, such as Asclepius or Apollo, associated with healing and premonition. Such enclaves were also populated by satyrs and dryads, embodying something even more ancient than the gods themselves. For this reason, entry and exit from such primal sources of power were strictly regulated and ritualized. “Temenoi” were open only to a dedicated, ritually purified priesthood. The groves were also closed to the public for most of the year, opening only for specific celebrations and feasts. These periods served as liminal times, during which the spheres of the sacred and the profane blurred into one another. In regular times, these spheres were also physically separated from the mundane world by sensory markers. Bush-hedges, fences, stone columns, and decorated gates with seals, bells, and guarding statues surrounded their perimeters. Besides these, most “temenoi” already had a unique spatiality, one that highlighted the place’s significance and invoked a sense of awe in visitors, even before the construction of visible markers. Such groves were hidden in the depths of valleys or were located in difficult-to-reach mountainous areas, or on the perimeters of dense forests, or caressed by rivers or other bodies of water.

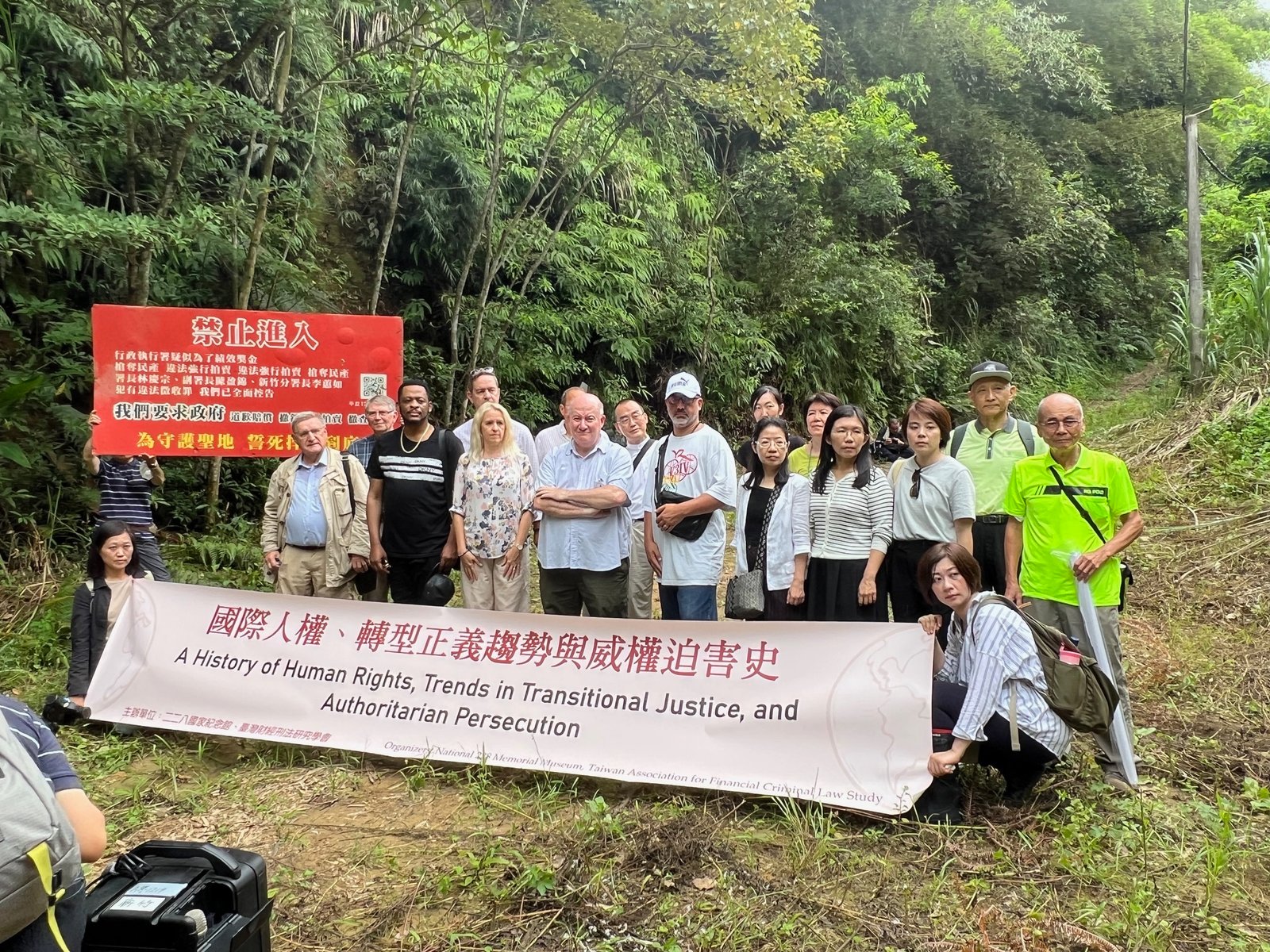

The pristine mountainous area of Miaoli, where the sacred land of the Tai Ji Men is located with 67 interconnected plots, fits this description in several respects. The environment immediately captures the visitor’s spirit: it is a tropical broadleaf forest with rivers flowing through it, surrounded by even larger bamboo forests, from which the dizi used to gather materials for their famous dragons used in dances.

Before the seizure of the land in 2020, Dr. Hong planned to construct a large assembly hall on this interconnected network of plots, along with supplementary educational and spiritual-cultivational structures. The plans were laid out to manifest something that the land had already been ready for: it was the perfect place to create a “temenos” for the Tai Ji Men. A sacred grove where the dizi may retreat and elevate their consciousness. A place where they could gather, discuss, study, and even retreat and recharge, far from the noise of the outside world. It is also worth noting that, in Tai Ji Men’s view, this land possesses an excellent magnetic field and feng shui, which can support disciples in their spiritual practice and advancement. In conclusion, the land was already prepared to serve as a spiritual home for the dizi.

It is also worth noting that in Taiwan, each religious group typically has sacred spaces that serve as symbols of the organization. These locations showcase spiritual and communal narratives and serve as banners under which followers and practitioners may gather for significant events. They also serve as signaling posts, communicating that the movement that built it is alive and ready to face any power that dares to storm the walls of these spiritual fortresses. Once such a sacred space is built, a prominent and decorated gate is usually erected at the boundary of the land, marking the conclusion of “temnéndus,” the process of ritually cutting out a sacred land from the profane world. The separation of these two spheres at this point is signaled by a physical object, which can be seen by anyone who passes by, not just the followers themselves. In this understanding, the sacred land innately holds spiritual power. The structures built on it only highlight and enhance these traits, and the act of enclosing the land seals the power within, accumulating and directing it for ritual purposes.

At one point, Tai Ji Men had one such land. Tragically, before the act of “temnéndus” could even begin, this land was unjustly nationalized. As such, the construction was halted, and the plans were largely lost in the turmoil of the following decade. Today, these planned buildings are still unbuilt, the sacred space is still “intemnéndus”—non-separated, part of the mundane world.

Still, the mountain calls to the Tai Ji Men. They visit the available plots of land, but coming here invokes a sense of sadness, which, for some dizi, is too much to bear. Being here reminds them of past, undealt-with bitter memories. At the same time, returning to the land of the unbuilt “temenos” gives the dizi a sense of home and belonging. They still gather bamboo from the remaining plots, and they still fulfill their duties to the land that holds a promise: a future central space, a sacred grove, and a spiritual retreat for the Tai Ji Men.

The act of returning here is similar to what Carl Gustav Jung suggests about one’s own, internalized temenos: here, the dizi may still conduct “work”—engage with the subconscious, achieve higher consciousness, commune with greater truths, and practice self-cultivation.

In the end, the land destined for Tai Ji Men still exists. It calls for the dizi, and they answer. They practice Qigong under Dr. Hong’s guidance. They advocate for good consciousness and a better tomorrow. However, their unbuilt center, the unseparated “temenos,” is a reminder that this movement was unjustly charged, harmed, and reparations are still unconcluded. Every religion has the right to designate places as spiritual homes. Miaoli could be one such place for the Tai Ji Men in Taiwan. Just as the “temenoi” of classical antiquity, these places shall be kept intact and unharmed by secular powers. At the same time, they shall be kept open to anyone who is anointed to indulge in the esoteric mysteries of self-cultivation and awakening consciousness.

Márk Nemes is a historian and a graduate in the academic study of religions. He received his doctorate in philosophy at the University of Szeged’s PhD program in 2025 and works as a researcher at the Hungarian Academy of Arts’ Research Institute of Art Theory and Methodology. As an awardee of the Hungarian National Eötvös Scholarship, he served as a visiting researcher at CESNUR from 2023 to 2024. For the past 10 years, he has focused on researching new, alternative, and emergent forms of religiosity in Hungary, Iceland, the US and most recently, in Italy. Since 2025, he serves as the Deputy Director of CESNUR