“Religion, Secularism, and Love” by Ting Guo is about the political use of the world’s oldest control tool.

by Massimo Introvigne

“Roses are red, loyalty is too. Obedience is sweet, and dissent makes you blue.” If Valentine’s cards were written by the Chinese Communist Party, they might look something like this. Ting Guo’s “Religion, Secularism, and Love as a Political Discourse in Modern China” (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2025) is a book that unmasks the governments’ most seductive trick: turning love into politics, intimacy into ideology, affection into obedience. Ting Guo, an Assistant Professor of Cultural and Religious Studies at Chinese University of Hong Kong, brings a feminist (and queer) twist to a political history of love in China, yet it exposes the easiness of its manipulation.

Guo’s study is not about romance—it is about how “love” has been conscripted across centuries of Chinese history, from Confucian filial piety to Maoist devotion, and now to Xi Jinping’s paternal authoritarianism. The result is a genealogy of intimacy in chains, a reminder that in China, love has never been innocent.

In imperial China, love was never private. Confucianism enshrined filial piety as the highest virtue, and this familial devotion was seamlessly extended to the emperor. To love one’s parents was to love the sovereign; to disobey either was to betray the natural order. The family became the prototype of authoritarian governance, with loyalty dressed up as affection.

This was the first sleight of hand: turning love into duty, intimacy into hierarchy. The emperor was father, the people his children. Love was not a choice but an obligation.

By the early 20th century, love was rebranded as “bo’ai”—universal love. Sun Yat-sen invoked it as a theological-political force, mobilizing bodies for nationalist salvation. Love was no longer about family but about the nation. To love China was to sacrifice for it.

Here, Guo shows how love became a rallying cry for collective struggle. Love was the fuel for revolution, a banner under which obedience could be demanded.

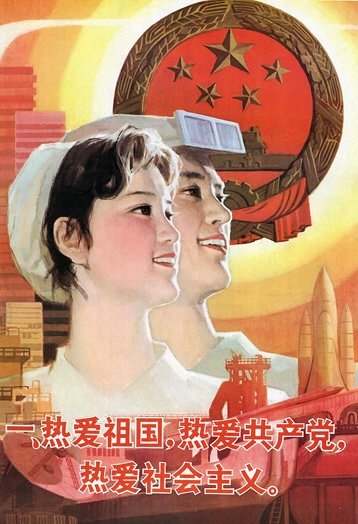

Under Mao, love reached its most authoritarian form. Citizens were told to love the Chairman as the ultimate beloved. The “Little Red Book” was not just scripture but a love letter. To love Mao was to love China, and to love China was to obey the Communist Party.

This was political religion at its most intimate: the leader as lover, the Party as family, the revolution as romance. Love was spiritual salvation, but salvation meant submission.

Today, Guo argues, authoritarian traditionalism reinvents Confucian “parental governance.” Xi Jinping’s China casts the Party as benevolent father, demanding filial devotion from its children-citizens. Campaigns for “harmonious society” and “family values” are less about compassion than about compliance.

Love is no longer private; it is a political duty. Citizens are told that obedience is affection, that loyalty is intimacy, that dissent is betrayal of the family. Authoritarianism is disguised as tenderness.

What Guo makes clear is that love in Chinese political discourse is engineered, appropriated, and deployed to justify control. The rhetoric of love masks coercion: “We love you, therefore obey us.”

This is not unique to China, but China has perfected the art. Love becomes a velvet glove over an iron fist. Citizens are seduced into obedience, told that tyranny is affection, that surveillance is care, that repression is protection.

Guo’s book is a warning. Authoritarian regimes everywhere have learned the trick: to dress control in the language of care, to disguise coercion as compassion. When rulers speak of love, beware.

Because in China, love has long been the language of control. And in today’s world, the authoritarian alchemy of love is spreading.

The book is about how authoritarianism seduces. Guo unmasks China’s, and the Party’s, greatest trick: making tyranny feel like family.

It is a book that should be read not with roses in hand but with sharp suspicion. In China, love is never just love—it is politics in disguise.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.