The “cult” rhetoric obscures what happened in Jonestown, the Solar Temple, Heaven’s Gate, and Kanungu—and why.

by Massimo Introvigne*

*A paper presented at the Occult Convention IV, Parma, September 6, 2025.

Article 4 of 5. Read article 1, article 2, and article 3.

The tragedy at Jonestown on November 18, 1978, remains one of the most devastating episodes of mass death in modern history. Over 900 members of the Peoples Temple died in a coordinated act of murder-suicide in the Guyanese jungle. To understand this event, we must examine the ideological, political, and esoteric dimensions of the movement led by Jim Jones.

The Peoples Temple was founded in Indiana in the 1950s by James Warren “Jim” Jones, a charismatic preacher who blended Pentecostal enthusiasm with socialist ideals. Inspired by Marxism and the civil rights movement, Jones promoted racial integration, communal living, and economic equality. His teachings attracted a diverse following, including many African Americans, seniors, and economically marginalized individuals.

Jones moved the Temple to California in the 1960s, where it expanded its political influence. He built connections with politicians, journalists, and activists, portraying the Temple as an example of progressive religion. Critics, however, claimed that beneath this public image, the organization was highly controlled, characterized by surveillance and authoritarian practices.

In 1977, amid media attention and legal probes, Jones relocated his followers to a secluded compound in Guyana. Jonestown was intended as a utopian socialist society, aiming to escape capitalist exploitation and racial discrimination. Members surrendered their assets, severed family ties, and adopted communal work.

Life in Jonestown was difficult. Food was limited, medical facilities were few, and dissent was harshly suppressed. As Jones’ health declined, his sermons turned more paranoid and apocalyptic, warning of CIA plots, fascist takeovers, and nuclear destruction. The community was cut off from the outside world, both physically and ideologically.

In November 1978, U.S. Congressman Leo Ryan went to Jonestown to look into reports of abuse, possibly exaggerated by anti-cult circles. Several Temple members wanted to leave with him. As Ryan and his team got ready to leave, they were ambushed at the airstrip. Ryan, three journalists, and a defector were killed.

That evening, Jones convened the community and delivered his final speech. He framed the impending mass suicide as an act of “revolutionary suicide,” a protest against an inhumane world. Cyanide-laced Flavor-Aid (misidentified in popular culture as Kool-Aid) was distributed, and over 900 people died, including more than 300 children.

The term “revolutionary suicide” was borrowed from Black Panther leader Huey Newton, who used it to describe resistance against systemic oppression. Jones reinterpreted it to justify mass death, claiming that life under fascism was not worth living.

Scholars such as John R. Hall and David Chidester contend that Jonestown should be viewed in the context of American religious innovation, leftist politics, and apocalyptic esotericism. The Temple was more than just a religious organization; it served as a political experiment, a communal utopia, and a hub of ideological extremism.

Importantly, many members did not choose to die. Evidence suggests that some were coerced, others murdered. The event defies simple categorization and challenges our understanding of agency, belief, and leadership.

The Order of the Solar Temple (Ordre du Temple Solaire, OTS) was an esoteric group that became infamous in the 1990s following a series of ritual suicides and murders across Switzerland, Canada, and France. The deaths of more than seventy members from 1994 to 1997 shocked the global community and sparked critical questions about the connections between Western esoteric traditions, charismatic leadership, and apocalyptic ideals.

Luc Jouret and Joseph Di Mambro founded the OTS, which integrated various esoteric traditions, such as neo-Templarism, Rosicrucianism, gnosticism, and ceremonial magic. Its members believed in a spiritual elite meant to lead humanity through cosmic transformation.

The group’s mythology focused on the Knights Templar, suppressed in the 14th century, and their alleged continuation as keepers of ancient knowledge. The OTS asserted that they continued this lineage, aiming to establish a new spiritual order.

Di Mambro, seen as the spiritual leader, conducted complex rituals. Jouret, a trained homeopath and public speaker, acted as the charismatic representative of the movement.

In October 1994, 53 members of the OTS died in Switzerland and Quebec. Some suffocated themselves with plastic bags. Others were shot, some drugged, and many bodies were arranged in ritualistic patterns. Subsequent deaths occurred in 1995 and 1997, bringing the total to 74.

The suicides were depicted as “transits” to a higher spiritual realm. Members thought they were escaping a corrupt world and entering a divine dimension.

Di Mambro had foreseen his death and that of his daughter, claiming she was the cosmic child meant to guide humanity. Internal conflicts, financial pressure, and outside scrutiny may have hastened the group’s downfall. The group’s suicides weren’t acts of desperation but sacred rites, symbolizing the shift from ordinary life to divine purpose.

The OTS challenges the stereotype of desperate or deluded followers. Many members were educated, middle-aged professionals with stable lives. Their participation shows how esoteric beliefs can reframe death as transcendence.

The case also illustrates how esoteric authority and apocalyptic expectation can produce lethal outcomes, especially when dissent is suppressed and external threats perceived as existential.

Heaven’s Gate was a UFO-based religious group that ended with the mass suicide of 39 members in Rancho Santa Fe, California, in March 1997. The group’s beliefs blended Christian millenarianism, New Age spirituality, and science fiction, forming a unique esoteric framework where suicide was seen as “graduation” to a higher existence.

Founded in the 1970s by Marshall Applewhite (“Do”) and Bonnie Nettles (“Ti”), Heaven’s Gate taught that Earth was on the verge of being “recycled,” and that salvation involved leaving the human body to join extraterrestrial beings in the “Next Level.”

Initially, the group thought physical ascension was possible—that members could be taken aboard a spaceship in their earthly bodies. However, after Ti died in 1985, Do updated the theology: the body was just a “vehicle,” and death was needed to free the soul.

Members lived communally, practiced celibacy (some decided to be castrated), and adhered to strict behavioral codes. They studied Applewhite’s teachings, which were shared via videos and online resources. The group maintained a website and interacted with outsiders, portraying themselves as rational seekers of truth.

In March 1997, the group thought the Hale-Bopp comet was accompanied by a spacecraft sent to collect them. Over several days, members took barbiturates and alcohol, then covered their heads with plastic bags, and assumed coordinated lying positions, waiting to die. They all wore identical clothing, with a travel bag beside each.

Farewell videos recorded before the suicides (the originals of which were bequeathed to my organization, CESNUR, and given personally to me by a surviving member who then also committed suicide) show members expressing joy and anticipation. They did not view their actions as suicide but as a necessary step to reach the Next Level.

In “Heaven’s Gate: America’s UFO Religion,” American scholar Benjamin Zeller argues that the group’s theology was internally coherent and deeply rooted in American religious traditions. Heaven’s Gate drew on apocalyptic Christianity, Gnostic dualism, and New Age cosmology.

Scholars have emphasized the ritualized nature of the deaths. The suicides were carefully planned, symbolically charged, and framed as spiritual liberation.

Heaven’s Gate contests the idea that suicide is always irrational or pathological. Its members were articulate, dedicated, and driven by spiritual beliefs. Their actions illustrate a profound reinterpretation of death as a form of transformation.

The group also illustrates how esoteric belief systems can evolve in response to theological crises. Ti’s death forced a doctrinal shift, and Applewhite’s charisma sustained the movement through uncertainty, although ultimately it destroyed it.

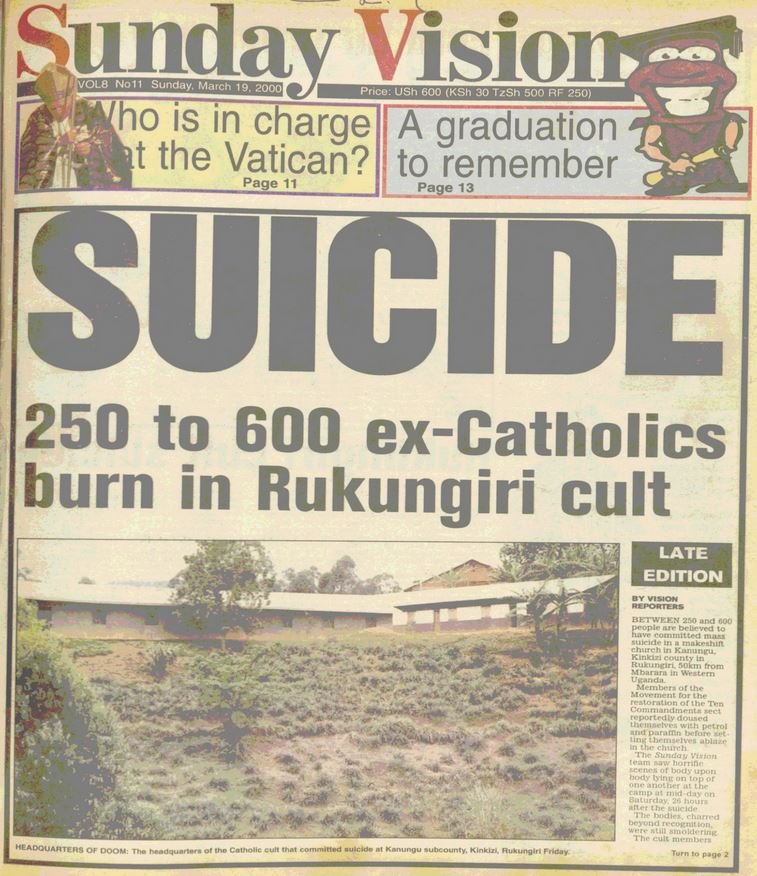

The Movement for the Restoration of the Ten Commandments of God (MRTCG) was a Ugandan religious group that ended with one of the deadliest mass deaths linked to a religious organization in recent times. In March 2000, over 780 people died during a series of coordinated killings and a final blaze at the group’s compound in Kanungu. To understand this tragedy, we must examine the movement’s origins, beliefs, and esoteric reinterpretations of Catholic teachings.

The MRTCG was established in the late 1980s by Credonia Mwerinde and Joseph Kibweteere, who claimed to have visions of the Virgin Mary. The movement arose from a broader environment of Marian apparitions and visionary Catholicism in East Africa, especially after the recognized apparitions at Kibeho, Rwanda.

Kibweteere was a former politician and devout Catholic, while Mwerinde had a more enigmatic background, reportedly claiming to be a reformed prostitute in imitation of Mary Magdalene. Together, they attracted followers disillusioned with the institutional Church, the AIDS epidemic, and political corruption.

The movement incorporated priests and nuns who were later defrocked, including Father Dominic Kataribaabo, a U.S.-educated Ugandan cleric. It was legally registered and operated a boarding school until 1998, when its license was revoked due to concerns about child welfare and politically subversive teachings.

The MRTCG underscored the importance of strictly following the Ten Commandments as the sole route to salvation. Its members believed the world was nearing an apocalypse, and only those who carefully obeyed the commandments would survive. To prevent lying, communication was limited, and sign language was used on specific days.

Sexual activity and soap use were prohibited, the latter seen as a sign of vanity. Members followed fasting routines and adopted monastic lives, engaging in nightly prayers and strict schedules. The movement issued a booklet called “A Timely Message from Heaven: The End of the Present Time,” which new members must study thoroughly.

The group predicted the end of the world on December 31, 1999. When the prophecy failed, internal tensions rose. Leaders reportedly began planning a “final purification,” culminating in the events of March 2000.

On March 17, 2000, hundreds of members gathered in a converted church in Kanungu. After a night of prayer, the building was set ablaze, killing all inside. Subsequent investigations uncovered mass graves at other MRTCG properties, revealing that many victims had been murdered before the fire.

Historian Jean-François Mayer’s research indicates that the deaths were deliberately planned. While some members may have agreed to die, others were clearly victims of murder.

The MRTCG should not be seen just as a fringe group. Its theology was based on conservative Catholicism, Marian devotion, and apocalyptic expectations. It reflected broader concerns in Ugandan society—about disease, corruption, and spiritual decline.

Mayer argues that the movement’s esotericism was selective and syncretic, blending official Catholic teachings with visionary revelations and millenarian urgency.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.