While Jains seek spiritual liberation at the end of life, Buddhist self-immolation and Muslim suicidal bombing are different forms of politico-religious actions.

by Massimo Introvigne*

*A paper presented at the Occult Convention IV, Parma, September 6, 2025.

Article 3 of 5. Read article 1 and article 2.

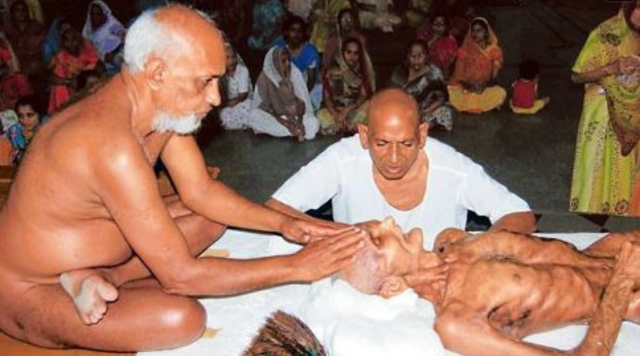

In Jainism, Sallekhana is a sacred ritual involving a voluntary fast to death. It is not regarded as suicide by Jains but is often labeled as such by outsiders. Both monks and laypeople approaching the end of life practice it, embodying core Jain values of non-violence (ahimsa), detachment, and karmic purification. The practice involves gradually reducing food and water intake while meditating, praying, and reflecting spiritually. Its goal is to diminish the body and passions, shed karmic ties, and prepare the soul for liberation (moksha).

This regulated process requires full awareness, public declaration, and spiritual guidance. Jain texts describe the ritual, where participants renounce solids, then liquids, and all sustenance, seeking forgiveness and reflecting on their actions. The process can last weeks or months and is ideally overseen by a Jain monk.

Sallekhana is not viewed as suicide by Jains because it is not motivated by passion, despair, or violence. Jain philosophy distinguishes between death from karmic entanglement and death embraced as spiritual liberation, considering it the culmination of a life lived ethically.

Legally, Sallekhana faced challenges; in 2015, the Rajasthan High Court banned it, equating it with suicide under Indian law. The Jain community protested, asserting it is protected under Article 25 of the Indian Constitution, which guarantees freedom of religion or belief. The Supreme Court lifted the ban later that year, recognizing it as a legitimate religious practice.

This practice prompts meaningful discussions about religious freedom and the sanctity of life, questioning Western views of suicide that often suggest psychological distress. In Jainism, death can be a deliberate, ethical, and even joyful act of transcendence. Sallekhana challenges secular legal systems by framing death as a sacred act. It is not a rejection of life but the culmination of spiritual discipline. This practice raises questions about autonomy, religious liberty, and the state’s role in regulating rituals. It demonstrates how ritual suicide can be rooted in a philosophy of nonviolence and spiritual purification, rather than protest or despair.

Self-immolation, which involves setting oneself on fire, is a highly striking and symbolically powerful form of protest. It also exists outside of religious contexts, such as Czech student Jan Palach, who set himself on fire and died in 1969 to protest the Soviet invasion of his country in 1968. It has been employed in Buddhist traditions to convey spiritual dedication, political opposition, and moral anger. Although Buddhism usually discourages suicide, self-immolation has become a ritualized act in specific historical and cultural contexts.

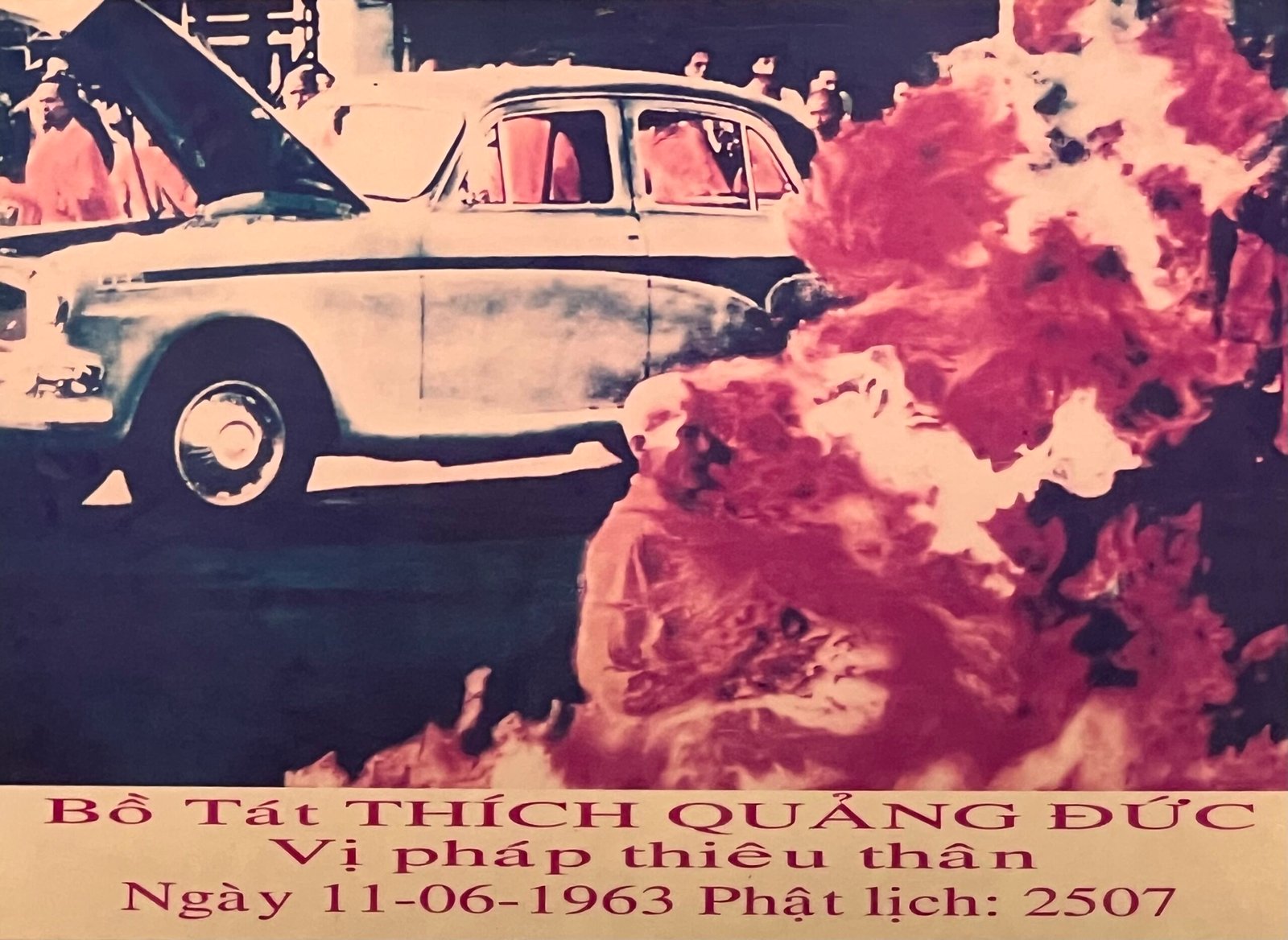

On June 11, 1963, Vietnamese Mahayana monk Thích Quảng Đức sat in the lotus position at a busy intersection in Saigon, poured gasoline over himself, and set himself on fire. He did this as a protest against the South Vietnamese government of President Ngô Đình Diệm, which was accused of persecuting Buddhists to favor the Catholic minority.

The act was carefully organized. Quảng Đức notified other monks of his plan, and the protest was designed to attract maximum attention. Journalists attended, and photos of the burning monk spread worldwide, becoming powerful symbols of defiance.

Quảng Đức’s self-immolation was a deliberate act grounded in Buddhist principles, not an impulsive act of desperation. In Mahayana Buddhism, the bodhisattva ideal emphasizes self-sacrifice for others’ benefit. The “Jātaka Tales,” recounting the Buddha’s previous lives, feature self-immolation stories to save others or show compassion.

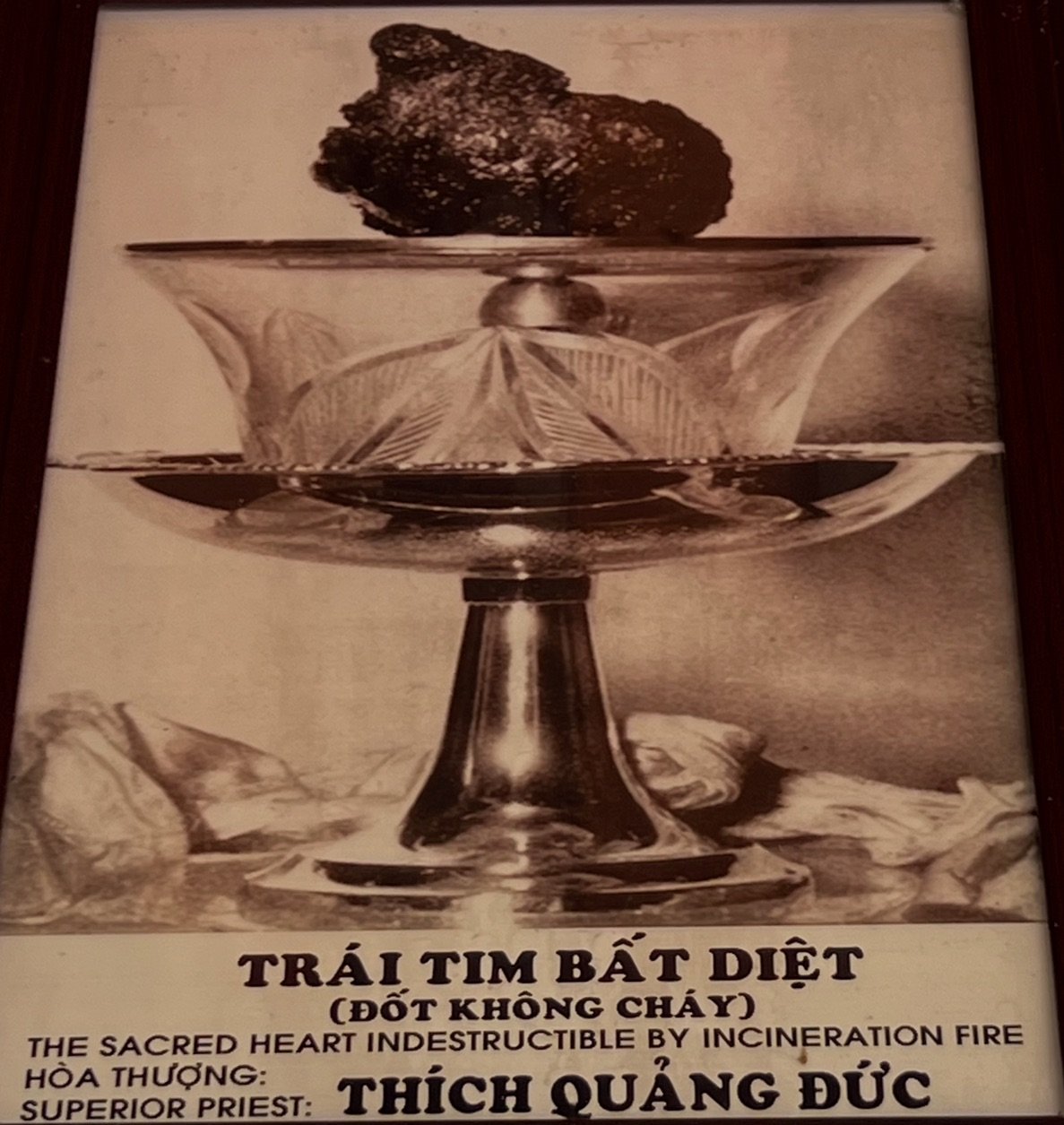

The monk’s body was cremated afterward, but his heart is said to have remained intact, becoming a revered relic. His actions inspired additional protests and played a role in the eventual collapse of Diệm’s regime.

Since 2009, more than 160 Tibetans—monks, nuns, and laypeople—have set themselves on fire in protest against Chinese rule. These incidents mainly occurred in the Tibetan Autonomous Region and nearby provinces with large Tibetan populations, like Sichuan and Qinghai.

Tibetan self-immolation is a recent development that is not traditional in Tibetan Buddhism. It has arisen as a form of protest amid the sociopolitical crisis in Tibet, especially after the 2008 uprisings and the increased Chinese repression.

The motivations for these actions are intricate. Protesters typically demand the return of the Dalai Lama, religious liberties, and Tibetan self-governance. Farewell notes and recordings show a blend of spiritual faith and political urgency. Although the Dalai Lama has stated he does not support self-immolation, he has acknowledged the bravery and intentions of those who choose to do it.

Tibetan self-immolation is a form of Buddhist nationalism that combines religious identity with political resistance. It is viewed not as suicide but as a sacrificial act meant to attract international attention to Tibetan suffering.

From a doctrinal perspective, self-immolation questions Buddhist principles of nonviolence and the sacredness of life. However, in Mahayana traditions, the motive behind the action—such as compassion, protest, or awakening—can turn it into a spiritual act.

These cases show how Buddhist ethics can be reinterpreted during crises, and how ritual suicide becomes a form of protest when other options are unavailable.

Suicide terrorism remains one of the most debated and misunderstood topics in modern religious conversations. Although mainstream Islamic teachings condemn suicide, radical organizations have reinterpreted the concept of martyrdom (shahada) to legitimize acts of self-sacrifice carried out in the name of jihad.

As mentioned earlier in this series, the Qur’an explicitly prohibits suicide, and traditional Islamic law considers it a grave sin with harsh repercussions in the afterlife.

In Islamic tradition, martyrdom holds a highly esteemed position. Martyrs are assured paradise, and their deaths are regarded as noble sacrifices. This creates a theological tension: although suicide is condemned, dying in battle for the faith is considered a glorified act.

Radical groups exploit this ambiguity. They redefine suicide bombings as acts of martyrdom, claiming that the intention is not self-destruction but the defense of Islam. Mainstream scholars do not support this reinterpretation, but it has gained traction in militant circles.

“The Market of Martyrs,” a book I co-authored with American sociologist Laurence R. Iannaccone, explores how economic models explain suicide terrorism. We suggest that terrorist groups operate as ideological businesses, providing spiritual incentives, social recognition, and a sense of community in return for the ultimate sacrifice.

Suicide bombers are not irrational; they make calculated decisions based on perceived benefits—spiritual, familial, and ideological. Organizations target individuals with strong religious identities and social grievances. They offer narratives of heroism and transcendence. The supply of suicide bombers depends on ideological demand. Charismatic leaders act as “entrepreneurs,” crafting compelling theological justifications.

The book challenges the notion that poverty or mental illness drives suicide terrorism. Many bombers are educated, middle-class, and socially integrated. Their actions are framed as altruistic, aimed at defending the ummah (Muslim community) and achieving divine reward.

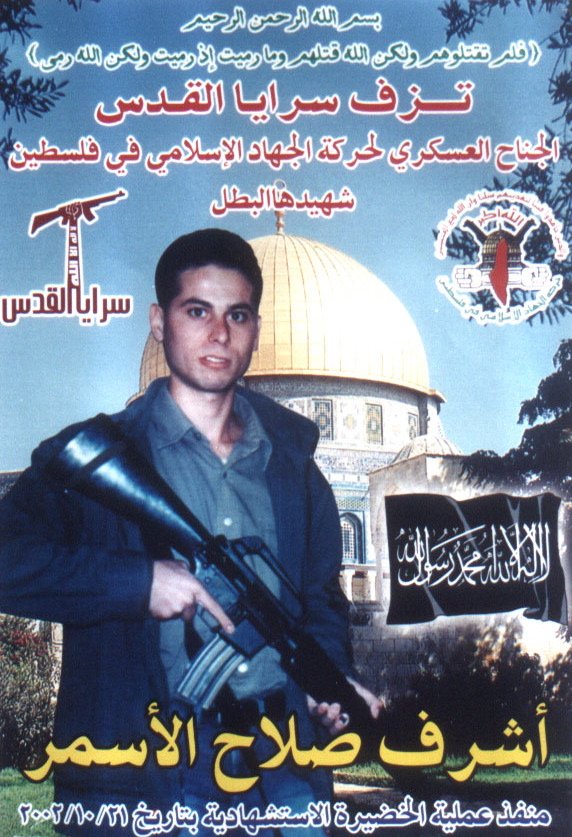

Groups like Hamas and Islamic Jihad have used suicide bombings as tactical weapons against Israeli targets. Martyrs are celebrated with posters, funerals, and financial support for families. Al-Qa’ida and ISIS institutionalized suicide terrorism, training bombers, and glorifying their deaths in propaganda videos. In Nigeria, Boko Haram has deployed female suicide bombers to attack civilian and military targets.

These acts go beyond politics; they are ritualized and embedded within esoteric Islamic eschatology. Key themes include the promise of paradise, sin purification, and defending divine law.

Mainstream Islamic scholars have condemned suicide terrorism as a misinterpretation of Islamic teachings. Fatwas from institutions like Al-Azhar label such acts “haram” (forbidden). They stress that martyrdom should only happen in legitimate self-defense, not through the killing of innocent people.

However, the continued occurrence of suicide terrorism demonstrates how obscure apocalyptic beliefs can take precedence over traditional doctrines. It also illustrates how ritual suicide, in this context, transforms into a weaponized form of religious expression.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.