The September 2022 rules are hailed as progressive and liberal. But they are unlikely to improve the situation of those arrested for “separatism” or religion-related offenses.

by Hu Zimo

On September 9, 2022 the Supreme People’s Court, the Supreme People’s Procuratorate, the Ministry of Public Security, and the Ministry of State Security enacted new “Provisions on Several Measures Concerning Release on Bail Pending Trial.”

They have been hailed by legal scholars as a significant improvement with respect to the previous regulations on bail, which dated back to 1999. The latter were very restrictive. Release on bail might be granted if the prosecutor was seeking a jail penalty of less than six months, if defendants were regarded as not dangerous, or if they were disabled or pregnant women. “Might” was the operative word, as the discretional power of the authorities was total. However, in recent years, more prisoners awaiting trial were released on bail, particularly after a campaign was started to make prisons less crowded during the COVID-19 epidemic.

The new rules state that the prisoners “should” be released on bail if the conditions occur. However, it is unclear what recourses they may have if this does not happen.

On the other hands, conditions for being released on bail remain strict. Defendants should not enter places or associate with persons connected with the crime they are accused of. They should also not engage in:

“(1) Activities that may lead them to commit crimes again;

(2) Activities that may have a negative impact on national security, public security and social order;

(3) Activities related to the suspected crime;

(4) Activities that may hinder litigation;

(5) Other specific activities that may hinder the execution of release on bail pending further investigation.”

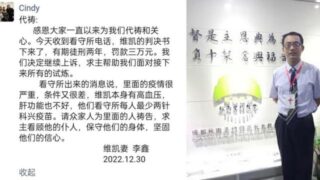

Several cases of defendants accused of being members of a xie jiao or of having engaged in illegal religious activities who were denied bail under the old rules were reported to Bitter Winter. The rationale was that, unless they signed a statement renouncing their faith, if released on bail they would likely continue to engage in the same activities they were being prosecuted for.

This situation is unlikely to change with the new rules. Unless defendants surrender to the pressure and renounce their faith, the authorities may argue that it would be impossible for them “not” to associate with people or engage in activities connected with their “crimes” once released. The same applies to political dissidents or Uyghurs, Tibetans, and others accused of “separatism.”

The new rules do broaden the possibilities of being released on bail. But not for everybody.