The dissolution order that hit the Family Federation last March violates Japan’s international law obligations.

by Patricia Duval*

*A paper presented at the conference “Resilient Memories in East Asia: Remembrance, Acknowledgment, Reconciliation,” Vytautas Magnus University, Kaunas, Lithuania, October 10–11, 2025.

After World War II, Japan wished to regain prestige amongst the international community when it adopted its new Constitution and committed to protecting fundamental rights, particularly the right of the Japanese people to freedom of religion or belief.

However, Japan has retained a very troubling exception to civil liberties in its Constitution and laws to this day, in the name of “public welfare.”

This vague and open-ended restriction to individual freedoms is not worthy of a democracy but would rather belong in a banana republic or a dictatorship where opposition movements or undesired minorities are labelled as contrary to the public welfare, with the State deciding what constitutes the welfare of citizens.

It is particularly questionable when it comes to freedom of religion or conscience.

Yet, based on this vague and arbitrary notion, the Japanese authorities are now on the verge of dissolving the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification, formerly the Unification Church, a religious corporation that has gathered around 600,000 followers in Japan.

This is why, on October 1st, four United Nations Special Rapporteurs publicly issued a press release to express their concerns about this alarming situation in Japan.

Let us now examine the context of such a situation.

The Japanese members of the Unification Church have been harassed and stigmatized in Japan over the last decades.

They have often been treated as if they were an ethnic minority, accused of being “anti-Japan” because the founders of the Church are a Korean couple, Reverend Moon and his wife, and the Church itself originated in Korea.

Historically, Japanese people have often harboured a sense of superiority over Koreans and tended to look down on them, in the wake of the past colonization of Korea by Japan.

This dynamic contributed to severe rejection by families when one of their members joined the Unification Church, driven by three reasons rooted in ethnic prejudice: (1) the fact that the founders are Korean, (2) the religion’s Korean origins, and (3) the fear that believers might be forced into marriages with Koreans.

This prejudice has been instrumental in leading families to resort to violent “deprogramming” of their kin who had joined the Church.

For nearly half a century, the government has given carte blanche to extreme anti-cult lawyers and consensual religions to organize the “deprogramming” of Unification Church members by force: kidnappings by trickery and illegal confinements by families, followed by imposed indoctrination against the Church’s beliefs by Protestant pastors.

Thousands of parents were abused and talked into subjecting their adult children believers to deprogramming.

Then, those members were pressured by their deprogrammers and lawyers to file financial claims against the Church to prove their real intention to abandon the faith and to be released from confinement.

This resulted in several civil litigations against the Church over the last four decades, led by politically motivated lawyers, the National Network of Lawyers against Spiritual Sales, who had pledged to eliminate the Unification Church due to its fight against atheistic Communism in Eastern Asia.

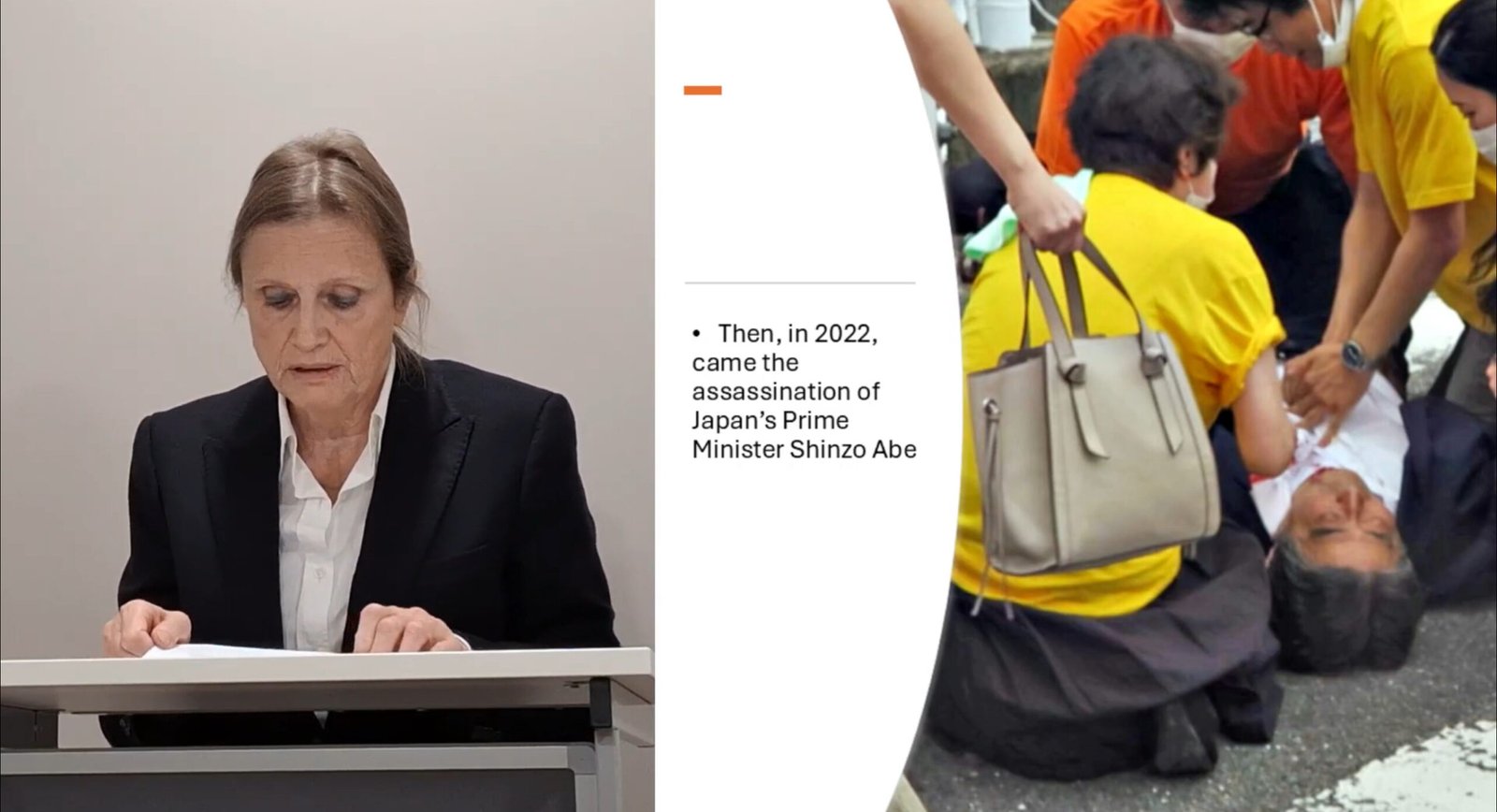

Then came the assassination of Japan’s Prime Minister, which was seen as a timely opportunity by these lawyers.

In 2022, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was shot dead by a man who held a grudge against the Church due to his mother’s past donations some twenty years before. He reportedly targeted Abe because he supported some Church humanitarian activities.

After the murderer’s arrest, a media blitz started against the Unification Church, initiated by the Lawyers’ Network.

At a press conference held by the Network in July 2022 in response to the assassination, the lawyers, one after another, vehemently condemned the Unification Church. They stated that “Abe’s assassin and his mother [were] 100% the victims, and the cult 100% the perpetrator.” They described the Church as “anti-social” and “a great evil.”

The lawyers and the media who were out to get the Church pinned an anti-Japan tag on it, due to its Korean origin.

Then, the sentiment that “a Korean-originated religion caused the assassination of Japan’s former Prime Minister” ignited anti-Korean hate sentiment amongst Japanese people. What had previously been confined to family-level hate emotions expanded into State-level sentiments.

The media frenzy pressured the Japanese Government to sever all ties with the Church, and, under the accusations from the Lawyers’ Network, making them responsible for the situation, Government officials initiated a dissolution procedure against the religious corporation.

This is how the Ministry, which oversees religious matters, in October 2023, filed a request for dissolution at the Tokyo District Court and maintained the following: “From around 1980 to 2023, Unification Church believers caused significant damage to many people by making them donate by restricting their free decision and preventing their normal judgment [accusation of brainwashing], which resulted in disrupting the peaceful lives of many people, including family members.”

In its claim of “disruption of peaceful lives,” the Ministry relied on thirty-two adverse civil court decisions in cases filed by former members, often after their “deprogramming,” for facts dating from twenty to forty years before. In all those cases, the civil courts found torts based on violation of “social appropriateness” or “social norms,” some vague and unwritten criteria that allowed arbitrary condemnations.

On this basis, the Tokyo District Court ruled on March 25th this year, ordering the dissolution pursuant to Article 81 of the law on religious corporations. Article 81 provides that a court may order dissolution if “in violation of laws and regulations, the religious corporation commits an act which is clearly found to harm public welfare substantially.”

The Court found that the Church violated “social norms” and therefore violated the law, although those “norms” are unwritten and undefined. They do not meet the criterion of predictability for being “prescribed by law” under the requirements for any limitation to freedom of religion or belief laid out at Article 18.3 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which Japan has signed and committed to.

The District Court’s dissolution order has been appealed at the Tokyo High Court and is currently pending review.

Now, let’s examine the concepts of “public welfare” and “social appropriateness” or social norms under international human rights standards.

The UN Human Rights Committee, created by the Covenant to monitor its implementation by State parties, has consistently urged Japan to stop using the notion of public welfare to limit freedom of religion or belief.

Japan ratified the Covenant in 1979 and accepted the Committee’s monitoring authority.

Since 1980—so one year later—the Committee has denounced the inclusion in Japanese law of the concept of public welfare to limit freedom of religion or belief and made the following recurrent demand: “The Committee reiterates its concern that the concept of ‘public welfare’ is vague and open-ended … and urges the State party to refrain from imposing any restriction on the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion unless they fulfil the strict conditions set out in article 18.”

Indeed, Article 18.3 of the Covenant provides: “Freedom to manifest one’s religion or beliefs may be subject only to such limitations as are prescribed by law and are necessary to protect public safety, order, health, or morals or the fundamental rights and freedoms of others.”

So, if protection of public safety or public order can allow limitations, on the contrary, protection of public welfare is not included in the list, which must be strictly interpreted, and does not allow any restriction to this freedom.

It can be concluded that the Japanese authorities have known for forty-five years that they had to review their internal laws to conform to the Covenant. However, they have consistently refused to do so under a fake pretense and violated their international commitments.

They are about to eliminate an entire religion on this illegal basis.

Additionally, the concept of “social appropriateness” or “social norms” opens the door to discrimination and domination by consensual religions—like what happened with the Protestant deprogrammers.

It directly conflicts with the Human Rights Committee’s standards in its Comment N° 22 on article 18: “The terms ‘belief’ and ‘religion’ are to be broadly construed. Article 18 is not limited in its application to traditional religions or to religions and beliefs with institutional characteristics or practices analogous to those of traditional religions. The Committee therefore views with concern any tendency to discriminate against any religion or belief for any reason, including the fact that they are newly established, or represent religious minorities that may be the subject of hostility on the part of a predominant religious community.”

Therefore, in the absence of any statute law violation or crime, public opinion hostility can never be a justification for courts to limit the right to manifest one’s religion or beliefs based on religious practices lacking so-called “social appropriateness” or violating “social norms.”

Yet, this has been the basis for the thirty-two civil tort decisions on which the dissolution order was issued.

This is the reason why four UN top experts in each of their areas of competence, the Special Rapporteurs to the Human Rights Council for freedom of religion or belief, for minority issues, for freedom of association and assembly and freedom of education, have issued a public statement on October 1st to warn Japan not to limit the manifestation of religion or belief unduly, outside the limitations strictly provided at Article 18.3 of the Covenant.

Let’s hope that Japan, through the Tokyo High Court, will review the legal basis of the first instance decision and reconsider the dissolution issue to comply with these requirements.

Patricia Duval is an attorney and a member of the Paris Bar. She has a Master in Public Law from La Sorbonne University, and specializes in international human rights law. She has defended the rights of minorities of religion or belief in domestic and international fora, and before international institutions such as the European Court of Human Rights, the Council of Europe, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, the European Union, and the United Nations. She has also published numerous scholarly articles on freedom of religion or belief.