“If” the Pope goes to Kiev, he may put together, and perhaps bring some order, to what some see as contradictory statements on the war.

by Massimo Introvigne*

*Translation of an op-ed published in the Italian daily “Il Mattino” on April 3, 2022.

What will happen if the Pope goes to Kiev? Of course in this question, for the time being, the operative word is “if.” Francis has said that the option to travel to the Ukrainian capital is “on the table.” That doesn’t mean a decision has already been made.

But “if” the Pope goes to Kiev, what would be the reasons for his visit? What would change in the Catholic Church’s position on the war? And what might change in the war itself?

It must be remembered that in the first weeks of the war Francis called for peace and spoke about the conflict in heartfelt tones. He expressed a suffering that it would indeed be ungenerous not to consider sincere. However, he did not condemn the Russian aggression unequivocally. Both in the United States and in Ukraine and Eastern Europe (less so in Italy), he received some criticism for this.

The Pope was not insensitive either to this criticism or to the tragic increase in the number of civilians, including children, killed by Russian bombings in Ukraine. On March 20, the tone changed. Francis recalled at the Angelus that “missiles and bombs have fallen on civilians, the elderly, children, and pregnant mothers,” and denounced “the violent aggression against Ukraine, a senseless massacre where slaughter and atrocities are repeated every day.”

Everyone understands that if there is a “violent aggression against Ukraine” there is an aggressor, and it is not the Ukrainians. The explicit reference to Putin and Russia was still missing, but this is part of the tradition of the Catholic Church, which did not even call Hitler and Stalin by name when it denounced their ideologies and crimes. Italian politicians such as Matteo Salvini and Silvio Berlusconi also condemn the war without ever mentioning Putin, but what for these politicians is tactics for Francis and the Catholic Church is tradition and strategy.

However, on March 24, speaking off the cuff to Catholic women, the Pope said he was “ashamed” when he read that “a group of states have committed to spend two percent of their GDP to buy weapons, as a response to what ‘is now’: this is madness,” adding, “The real response is not more weapons, more sanctions, more politico-military alliances, but another approach, a different way of governing the world.”

The risks in which Francis runs when he improvises without a prepared text are well known, and they are not only related to the Italian language (where he made some mistakes in this speech—and significantly no official English translation has been published by the Vatican). In Italy, everyone thought of a Papal support for former Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte (who in fact had been the first to commit to raise military expenses to two percent of GDP when he was in office) in his polemic against current Prime Minister Mario Draghi on the weapons’ budget, and generally the Pope’s words delighted the pro-Russian front.

Then, on March 25, Francis consecrated Russia and Ukraine to the Immaculate Heart of Mary in reference to the message that, according to Catholic believers, Our Lady in 1917 entrusted to three shepherd children in Fatima, Portugal. In that message, consecration was requested to deal with the risk of “Russia spreading errors throughout the world.” Russia, not Ukraine or the United States. Not everyone in the media is familiar with the uninterrupted dialogue between the Popes of the 20th and 21st centuries, all of whom took them very seriously, and the revelations of Fatima. But for those who did know, the reference was clear.

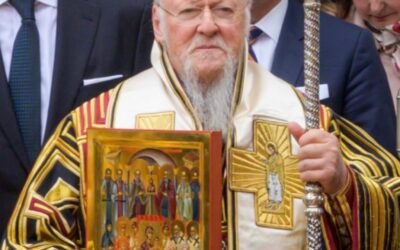

Now, the announcement of a possible visit to Kiev follows that of a forthcoming meeting with the Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church Kirill, one of Putin’s staunchest supporters: a meeting that had been planned for some time but seemed to have been cancelled.

Is there great confusion in the Vatican? I don’t think so. The Pope, speaking of other issues, has repeatedly reiterated that the “Catechism of the Catholic Church” promulgated by John Paul II remains the normative reference text for Catholics, which he too, as a “son of the Church”, obeys. Despite attacks by German bishops who would like to abandon a text that no longer persuades them on moral issues, renouncing the Catechism is not on the Vatican’s agenda.

Francis has entrusted Cardinal Secretary of State Pietro Parolin with the task of patiently explaining that the Catechism, on the one hand, in number 2315, harshly condemns the spending of States on armaments, and on the other, in number 2308, affirms that, until desirable international agreements convince all countries to renounce weapons of war, a State attacked by another has the right and indeed the duty to use them. There is no contradiction between the two theses.

Moreover, the Church also teaches that countries have the right to defend themselves against terrorism, and today al-Qa’ida and ISIS have real armies and weapons of war. If only these groups had weapons of war, and not those fighting them, we would all be at the mercy of terrorists.

It is true that the Catechism in number 2309—and Parolin recalled this—also states that recourse to arms is justified only when there are “serious prospects of success.” But this does not mean that it is unlawful to resist an enemy that appears to be much stronger in its military might, otherwise Christendom would have had to surrender many times to the Turks, and the world to Hitler. Nor does “success” mean total victory and destruction of the adversary. It also means winning on the ground more favorable conditions in a negotiation for peace, which without effective resistance would not have been a negotiation but an unconditional surrender.

“If” the Pope goes to Kiev, he will certainly be aware that his photograph with Zelenskyy will make a mighty contribution to the Ukrainian cause no matter what he says, even if later, we do not know when and where, he will also have his photograph taken with Patriarch Kirill. But if he goes to Kiev, he will go to say again what—with some confusion when he happens to speak off the cuff —he and the Church have been saying for some weeks.

That peace remains the polar star of any Christian discourse on conflicts, that this time there has been an aggression and resistance is legitimate, but the purpose of resistance is to arrive at balanced peace negotiations, where no one surrenders and everyone sacrifices something. A talk to Zelenskyy, of course, but so that he also means Putin.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.