Nepal imports technology from China—which is where data end up.

by Tenzin Dalha

The digital authoritarianism perfected in Tibet over the past decade has become a troubling blueprint for surveillance expansion across Asia, with Nepal emerging as a critical case study in how Chinese technology exports facilitate cross‑border monitoring of Tibetan communities while simultaneously undermining the sovereignty and democratic freedoms of recipient nations. The transformation of Tibet into what human‑rights advocates describe as an open‑air prison—characterized by “nets in the sky and traps on the ground”—represents not merely a domestic Chinese human‑rights crisis but a technological export model that threatens fundamental freedoms far beyond China’s borders.

Nepal has become a particularly significant node in this expanding surveillance network, representing both the geographic and political intersection where Chinese technological influence meets vulnerable Tibetan refugee populations. Recent developments in Nepal illustrate how Chinese surveillance technology serves dual purposes: advancing Beijing’s geopolitical interests while enabling the monitoring and suppression of Tibetan communities that China considers threatening to its political narratives. The Nepali government’s increasing adoption of Chinese surveillance infrastructure, driven by Belt and Road Initiative investments and deepening bilateral security cooperation, has created conditions in which Tibetan refugees in Nepal face unprecedented levels of monitoring and control.

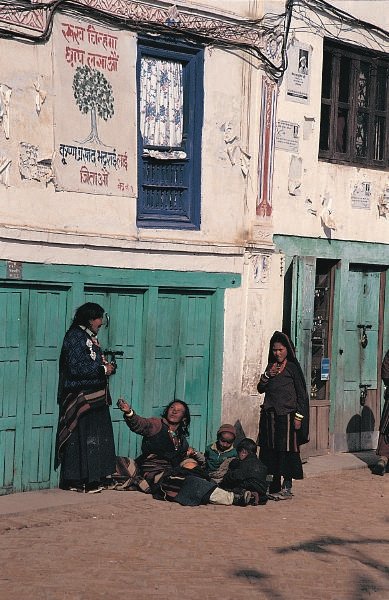

Reports from Kathmandu and other Nepali cities with significant Tibetan populations indicate that Chinese‑manufactured surveillance cameras have been installed in areas with high concentrations of Tibetan residents, particularly around monasteries, cultural centers, and refugee settlements. These installations coincide with Nepal’s broader security‑cooperation agreements with China, which have progressively constrained the activities of Tibetan communities in Nepal. The technological infrastructure enables real‑time monitoring of Tibetan gatherings, religious ceremonies, and political activities, with credible concerns that this data flows back to Chinese security agencies either directly or through information‑sharing agreements between the two governments.

The implications extend far beyond the immediate surveillance of Tibetan populations. Nepal’s adoption of Chinese surveillance technology represents a fundamental shift in the balance between state power and individual liberty within Nepali society itself. The same cameras and facial‑recognition systems installed ostensibly for public security can be—and increasingly are —deployed to monitor political dissent, track the movements of activists and journalists, and create comprehensive databases of citizens’ daily activities. The lack of robust data‑protection frameworks, transparency requirements, and independent oversight mechanisms in Nepal means that this surveillance infrastructure operates with minimal accountability or legal constraint.

China’s export of surveillance systems to governments worldwide, including Nepal, creates significant national‑security vulnerabilities for recipient states. These concerns are not theoretical but rooted in the fundamental architecture of Chinese technology companies and their relationship to the Chinese Communist Party. Chinese firms operating in the technology sector lack the independence from state control that characterizes companies in democratic systems. Under Chinese law, companies must cooperate with state intelligence agencies when requested, meaning that any data collected by Chinese surveillance systems is potentially accessible to Beijing. For Nepal, this creates a troubling scenario in which sensitive information about Nepali citizens, government operations, and security arrangements could be compromised.

The architecture of digital dependency that China constructs through these technology exports creates long‑term strategic vulnerabilities. This dependency gives China leverage over recipient nations, influencing their foreign‑policy decisions, economic relationships, and domestic political choices. Nepal’s position between India and China makes this dependency particularly consequential, potentially affecting regional security dynamics and forcing Nepal into difficult choices regarding its traditional policy of balancing relations between its two giant neighbors.

The global response to Chinese surveillance‑technology exports has been inconsistent and inadequate. While the United States has imposed restrictions on companies like Huawei and encouraged allies including Australia, Great Britain, New Zealand, and Canada to adopt similar measures, many developing nations continue to embrace Chinese technology due to its affordability and the infrastructure financing provided through Belt and Road Initiative projects. This creates a bifurcated global technological landscape in which democratic nations increasingly exclude Chinese surveillance technology while authoritarian and developing nations integrate it deeply into their national infrastructure.

For Tibetan communities, this technological expansion represents an extension of the surveillance state beyond Tibet’s borders, creating what activists describe as transnational repression facilitated by technology. Tibetans in Nepal and other countries with Chinese surveillance infrastructure face the reality that their movements, communications, and activities may be monitored by the same systems that control their relatives in Tibet. This creates chilling effects on political organizing, cultural‑preservation efforts, and even private communications, as individuals fear that their activities abroad could have consequences for family members in Tibet.

Empirical Evidence: The Case of Tashi

The operational reality of this surveillance network is powerfully illustrated through firsthand testimony documenting the experiences of individuals subjected to its mechanisms. Tashi— whose name has been changed to protect his identity and security—recounted his experience serving as a travel guide during a visit to Nepal that included stops at Boudhanath Stupa and several prominent Tibetan monasteries. His case provides crucial empirical evidence of how transnational surveillance functions in practice and the consequences faced by those monitored through these systems.

Upon returning to Tibet, Tashi was summoned by the Public Security Bureau for interrogation regarding his travel experiences. Officials questioned him extensively about his activities in Nepal, with particular emphasis on whether he had visited any monasteries or engaged with exile Tibetan communities. Cognizant of the potential repercussions, Tashi denied visiting these religiously significant sites, calculating that such a denial would protect him from punishment. This strategic response reflects the internalized understanding among Tibetans that certain activities—even when conducted legally in foreign jurisdictions—are considered violations of Chinese political requirements and are therefore subject to sanction.

To Tashi’s profound shock, Public Security Bureau officials confronted him with comprehensive documentation of his movements throughout Nepal. They presented detailed records, including precise timings of his visits to specific locations, photographs documenting his presence at various monasteries and religious sites, and possibly information about individuals with whom he had interacted. The specificity and completeness of this surveillance data fundamentally undermined his defensive strategy and demonstrated the technological sophistication of the monitoring systems deployed against him.

The consequences were immediate and severe. Officials confiscated Tashi’s travel‑guide license and passport, effectively ending his ability to work in tourism or travel internationally. He was subsequently subjected to prolonged interrogation sessions designed to extract detailed information about his contacts in Nepal, his activities at unauthorized religious sites, and his interactions with exile Tibetan communities. His case exemplifies a broader pattern experienced by numerous Tibetan travelers who discover, upon their return, that their movements abroad have been comprehensively monitored and documented—with activities that would be considered entirely legitimate religious practice in any other context transformed into evidence of political unreliability or suspected separatist sympathies.

Urgent Need for International Response

The situation demands urgent attention from the international community, civil‑society organizations, and democratic governments. The failure to restrict imports of Chinese surveillance technology means accepting a future in which the model of digital authoritarianism perfected in Tibet becomes normalized globally.

International mechanisms for technology governance must be strengthened to establish clear standards for surveillance‑technology exports, including transparency requirements, human‑rights impact assessments, and prohibitions on technologies specifically designed to facilitate repression. Democratic nations with advanced technology sectors should provide viable alternatives to Chinese surveillance systems, offering competitive pricing and financing arrangements that make rights‑respecting technology feasible for developing nations. Civil society organizations must continue documenting the human‑rights impacts of Chinese surveillance technology, generating public awareness and political pressure for policy change.

For Nepal specifically, civil society must advocate for robust data‑protection legislation and independent oversight of surveillance systems, as well as full transparency regarding agreements with China on technology imports and information sharing. The Nepali government should conduct comprehensive security reviewsof existing Chinese technology infrastructure and consider diversifying technology partnerships to reduce dependency on any single supplier. International organizations should support capacity‑building for Nepali institutions, enabling them to assess and manage technology‑security risks independently.

Conclusion

The warning I articulated at the Geneva Forum in 2019 remains acutely relevant today: Tibet’s all‑encompassing surveillance regime offers a troubling preview of what could spread globally if democratic societies fail to place firm limits on the import and deployment of Chinese surveillance technologies. For Nepal and other countries within China’s expanding sphere of influence, this future is no longer hypothetical—it is already unfolding. The surveillance cameras monitoring Tibetan communities in Kathmandu do not merely endanger one vulnerable population; they signal a broader transnational threat, illustrating how technology can be weaponized to erode freedom, dignity, and sovereignty beyond national borders. Confronting this challenge demands sustained international cooperation, principled and rights‑based policy decisions, and a clear recognition that technology governance is inseparable from the defense of human rights and democratic values in an increasingly interconnected world.

Tenzin Dalha is a research fellow at The Tibet Policy Institute, Central Tibetan Administration, studying social media and their implications and impacts on Tibetan communities both in Tibet and exile. His research interest also extends to exploring Chinese cyber-security policy.