A sweeping report reveals how rights guaranteed on paper falter under administrative habits, as the Tai Ji Men case demonstrates.

by Massimo Introvigne

The United Nations’ Two Covenants—the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR)—serve as essential foundations for human rights advocacy. Ratifying states agree to uphold a set of standards. When they fail to do so, civil society has both the right and the responsibility to hold them accountable to those commitments.

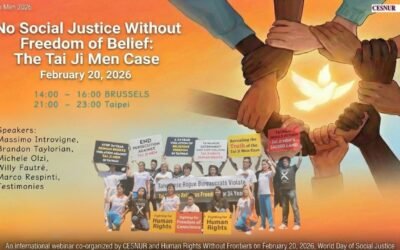

Taiwan, though not a member of the United Nations, voluntarily incorporated the Two Covenants into its domestic law in 2009. It is subject to periodic reviews by independent experts, who receive an official report. In view of the next review in 2026, several Taiwanese NGOs have presented shadow reports, addressing what they see as gaps in the government’s report.

“Bitter Winter” has published one such report, by the Tax and Legal Reform League, the Association of World Citizens (Taiwan), and others, addressing problems with the ICESCR. The same organizations have also prepared a report on the ICCPR, which we are summarizing here.

Taiwan likes to portray itself as a careful steward of the ICCPR. However, the Shadow Report we present suggests that the island’s administrative state has created a parallel legal system where the ICCPR is referenced in a symbolic way while its provisions are often twisted. The report claims that Taiwan’s tax and administrative systems regularly violate the Covenant’s guarantees. It starts with Article 2, which mandates non-discrimination, equality before the law, and effective remedies. The Tai Ji Men case, now in its thirtieth year, serves as the report’s key illustration. It shows how a modern democracy can slip into rights violations not through overt repression but through the slow, relentless pressure of bureaucratic power.

The authors note that Taiwan still lacks a complete anti-discrimination law, a shortfall directly related to Article 2(1). This legislative gap becomes starkly evident in the treatment of Tai Ji Men. The traditional red-envelope gifts from its disciples were taxed as if they were cram-school tuition, with a form of discrimination unique to them among martial arts, qigong, and religious groups. The National Taxation Bureau sent tax bills for six years without investigation or hearings, and without allowing Tai Ji Men to defend itself. The report describes this pattern as inconsistent with Article 2(3)’s requirement for effective remedies. When the Supreme Court later confirmed there was no tax evasion, the NTB first refused to withdraw the bills, then corrected them to zero, but with the exception of the bill for 1992, relying on a technicality. The eventual nationalization of Tai Ji Men’s sacred land in 2020, despite the criminal acquittal and several administrative victories, starkly illustrates unequal treatment and administrative stubbornness.

At the root of this issue lies a deeper structural problem. The Ministry of Finance relies on nearly ten thousand interpretive rulings, many dating back to the Martial Law era (1949–1987). These rulings act as de facto legislation, issued unilaterally without parliamentary oversight, opposing Article 2(2), which requires states to implement rights through proper legislation rather than obscure administrative orders. The Constitutional Court has frequently rejected such interpretations, and the Control Yuan has warned that the sheer number of these rulings creates “unpredictable tax risks” for citizens. Nonetheless, the system continues, supported by a tax bonus scheme that rewards officials for issuing and collecting tax bills. The report calls this a moral hazard that encourages overreach and undermines the impartiality required by Article 26’s guarantee of equal protection.

Even the Taxpayer Rights Protection Act, which is supposed to protect citizens, is described as structurally flawed. Rights-protection officers are appointed by the agencies they oversee, tax judges were approved in bulk despite doubts about their competence, and the statute of limitations is designed to protect the state’s ability to collect taxes rather than the citizen’s right to finality. In such an environment, the promise of Article 2(3)—a timely and effective remedy—becomes mostly theoretical.

The report highlights the “perpetual tax bill” phenomenon. When a court overturns a tax decision, the tax authority simply adjusts the numbers and issues a new bill, restarting litigation. Deadlines are reset, the five-year assessment period is ignored, and the taxpayer is trapped in a continuous loop of appeals. Criminal law allows retrials without time limits when new evidence favors the defendant, but administrative litigation imposes a five-year limit that prevents the correction of wrongful sanctions. Tai Ji Men has been caught in this loop for three decades, winning eighteen administrative decisions and receiving compensation for wrongful imprisonment, yet its property remains nationalized based on one disputed tax year. The report argues that this cycle breaches Article 14’s guarantee of fair proceedings and Article 2(3)’s demand for effective remedies.

The report also criticizes Taiwan’s exit bans as a coercive means of collecting taxes, a practice that violates Article 12 on freedom of movement. Individuals can be barred from leaving the country over relatively small debts, with decisions often made by tax agents without judicial review. This approach contradicts the principle that movement restrictions must be lawful, necessary, and proportionate. Less than five percent of those subjected to such bans actually pay their debts, indicating that this measure is both ineffective and intrusive. The human cost is exemplified by the case of an ordinary citizen who engaged in futures trading stranded abroad for nearly nine years due to an erroneous tax bill, missing significant moments in his children’s lives before finally being cleared.

Concerns about judicial fairness add further complexity. Taiwan’s recusal rules are so narrow that a judge can handle a case multiple times as long as he or she did not sign the previous ruling. In the Tai Ji Men case, one judge presided over the matter thirty-four times across different courts and stages, a situation described in the report as incompatible with Article 14’s requirement for an impartial tribunal. The authors recommend adopting the “appearance of unfairness” standard used in the United States and Japan, where even a reasonable suspicion of bias is sufficient for recusal.

The report also addresses Article 18, which protects freedom of thought, conscience, and religion. It argues that taxation has turned into a way for the state to interfere in spiritual and religious life. Excessive tax exemption requirements exclude many non-profit spiritual groups, violating the principle of tax neutrality. Tai Ji Men’s classification as a cram school after a 1996 political crackdown on religious and spiritual groups distorted its spiritual identity and infringed on the dizi’s (disciples) right to express their beliefs through gifts to their Shifu (Grand Master). The nationalization of its Miaoli land, meant for spiritual development, is compared in the report to seizing a church’s sanctuary.

Freedom of expression and assembly, as protected by Articles 19 and 21, are also at risk. The Ministry of the Interior has imposed broad prohibitions on “political activities” in national parks, allowing authorities wide discretion to limit speech. A volunteer protesting tax injustice was detained for eight hours for holding a sign criticizing an official, an incident that the report labels as state harassment. The Assembly and Parade Act, acknowledged as inconsistent with the ICCPR since 2012, remains unrevised, and some civic groups have faced a total rejection rate for protest permits. Even proposed amendments keep “safe distance” zones and police exclusion powers, indicating a continued unwillingness to give up administrative control over public gatherings.

The report concludes that Taiwan’s tax and administrative systems remain significant areas of human rights concern. The Tai Ji Men case is not just a one-off mistake but a structural issue—a sign of how unchecked administrative power can undermine rights protected under Articles 2, 12, 14, 18, 19, 21, and 26 of the ICCPR. Taiwan has a genuine democracy, but it also faces serious bureaucratic challenges. If the island wants to be a model for the region, it must acknowledge the uncomfortable truth that democracy involves more than just elections. It requires a daily commitment to keeping state power in check, especially when that power claims to be merely following the rules.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.