Never choose revenge to right injustice, never seek retaliation under the illusion of correcting wrongs: Tai Ji Men’s spectacular testimony thirty years after.

by Marco Respinti*

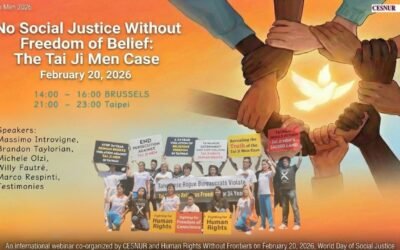

*Conclusions of the webinar “Entering the 30th Year of the Tai Ji Men Human Rights Case,” co-organized by CESNUR and Human Rights Without Frontiers on December 10, 2025, UN Human Rights Day, and in preparation for entering the 30th year of the Tai Ji Men case.

For some years now, we have been denouncing the profound unfairness of what we now justly call the “Tai Ji Men case.” Throughout this rich series of webinars, we have described, analyzed, and exposed the situation of Tai Ji Men, a menpai (similar to a school) of qigong, martial arts, and self-cultivation in the Republic of China (Taiwan). This spiritual movement was treacherously accused by some corrupt bureaucrats of tax fraud and even black magic. It was acquitted of all charges at every level of the Taiwanese judiciary, including the Supreme Court. Yet, incredibly, Tai Ji Men is still suffering the material consequences of such injustice—guilty of innocence and serving a sentence for no crime.

In this way, a case of blatantly denied justice has turned into a colossal case of religious liberty violation, insofar as the Shifu (or Grand Master) and the dizi (disciples) of Tai Ji Men have been prevented from freely carrying out their spiritual activities in accordance with the law of the Republic of China, forcing upon them an enormous burden and causing significant physical and psychological suffering.

We are rapidly approaching the end of 2025. In three weeks, we will celebrate the arrival of the new year 2026, and that new year will mark the 30th anniversary of the beginning of the absurd judicial persecution of Tai Ji Men. Throughout 2026, we will continue to commemorate—with initiatives and public denunciations—the thirty years of ordeal the movement has endured.

Thirty years is an enormous span of time. And yet, after all this time, and despite all the decisive judicial rulings that have completely cleared the movement of any wrongdoing, this absurd case remains open, unresolved, and frozen in a timeless limbo, as if that period of suffering and injustice was never meant to end. It seems that for Tai Ji Men—again, guilty of nothing and acquitted of every charge—time does not exist, and only an endless, unrelenting punishment without release is allowed to be.

But time does exist. It flows relentlessly and consumes everything. Time does not return, and no second chances are granted to time that has been misused. Thus, time stolen from Tai Ji Men through denied justice will never be compensated by any imaginable form of restitution, even if such compensation were to be granted one day, finally. All of this recalls what it is described—with the power of imagination and the force of the pen—in one of the masterpieces of world literature, “The Count of Monte Cristo” by French writer Alexandre Dumas (1802–1870).

Very few people are unfamiliar with this novel. All remember the dramatic journey of Edmond Dantès, a young sailor of exceptional integrity and promise, who becomes the victim of a conspiracy born of jealousy, ambition, and malice. Falsely accused of treason and arrested on the very day of his engagement, Edmond is condemned without trial and imprisoned in the infamous Château d’If, where he endures years of solitude, suffering, and despair. Within the prison, he meets Abbé Faria, a learned and compassionate fellow inmate who becomes his mentor and reveals to him the existence of an immense hidden treasure. After Faria’s death, Edmond manages a miraculous escape, recovers the treasure, and transforms himself into the enigmatic and immensely wealthy Count of Monte Cristo. Armed with new resources, a profound knowledge of human nature, and a clarity forged through suffering, the Count sets out to reward those who remained faithful to him and to bring down, with patient precision, those who betrayed him. His journey becomes not only a quest for justice and reparation, but also a profound exploration of vengeance, morality, and the possibility of forgiveness.

Now, the novel’s core question revolves around the concept of justice. Dumas uses this literary device to explore not only what justice is, but, more profoundly, who has the authority to administer it. While stating plainly that late justice is a form of profound injustice, the French writer struggles between the rival notions of revenge and true justice. Between the lines, we find him asking whether vendetta can really bring about serenity and peace of mind.

Another question subtly permeates every page of the novel. Since justice is a supreme good, Dumas conveys through Dantès, and since justice must ultimately be done, who then should enforce and deliver it when justice is delayed?

This question also resonates profoundly with Tai Ji Men, thirty years after the injustice that struck it and continues to affect it. Who should carry out justice when justice is constantly denied? In other words, wouldn’t it be better to accelerate justice, if and when it is delayed, even by means that may sometimes be unlawful, but which, in the end, are intended to right wrongs? In Dumas’ novel, Dantès constantly asks himself this question and repeatedly takes justice into his own hands to remedy its failings.

Dantès acts, in other words, as a substitute for God. This is a decisive point that once again connects the events of Dumas’ novel to the case of Tai Ji Men, which remains fundamentally a case of religious freedom denied to the detriment of a spiritual community. In short, if earthly justice fails to do its duty, and if God seems indifferent to the suffering of so many, should Tai Ji Men, thirty years later, not take matters into its own hands and become the agent of its own justice?

This question is a recurring classic throughout human history, arising whenever an individual or a group of people suffers an injustice and, at some point, decides that enough is enough, seeking to force reality to conform. Such force, of course, is always violent, so that what initially may have been a legitimate claim is transformed into a criminal act—into yet another injustice.

The long and terrible ordeal to which Dantès is subjected in “The Count of Monte Cristo”—years of indescribable suffering and wounds that will never fully heal—is an allegory of the human temptation to self-justice. Dantès does indeed execute justice himself; he builds his plans on resentment and carries out his revenge. Yet, in the end, he realizes that his moral and spiritual situation has only worsened. Revenge does not repair the injustice, and not even the ruin or death of his enemies can undo the pain he has endured. He comes then to understand, in the most extreme way, that serenity is not simply the arithmetic sum of material satisfaction and personal vindication, but a completely different way of seeing the world, oneself, and other human beings.

Tai Ji Men has superbly understood what Dantès comes to realize only at the end. Tai Ji Men understood it from the very beginning. It has never chosen revenge as a way to repair an injustice, never sought retaliation under the illusion of correcting wrongs, never disguised a new injustice under the superficial guise of justice in the vain hope of acting as arbiter of good, substituting itself for God. It has never done so, does not do so, and will never do so, because it knows that evil can produce only more evil, that another wrong cannot correct one wrong, and that two wrongs can never add up to a good.

Thirty years after the onset of the hardships that bashed this group of innocent people, Tai Ji Men has demonstrated an exemplary capacity for endurance and an equally exemplary generosity of spirit, refusing to be consumed by hatred and responding to the wrongs suffered with acts of goodness. The countless charitable and beneficial activities that Tai Ji Men has promoted during these thirty long years of suffering testify to this, and they constitute evidence of great value.

It is rare to see those affected by injustice resist the temptation to indulge in vengeance and instead turn to the sources of benevolence.

For this reason, it is essential to remind the world of the thirty years of suffering endured by Tai Ji Men: for they have also been thirty years of freely given good, extended to all. And while we hope that not a single day of the Tai Ji Men’s suffering is wasted, we are confident—indeed, certain—that many more days will be devoted by Tai Ji Men to acts of goodness, for the benefit of this wounded world.

Marco Respinti is an Italian professional journalist, member of the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), author, translator, and lecturer. He has contributed and contributes to several journals and magazines both in print and online, both in Italy and abroad. Author of books and chapter in books, he has translated and/or edited works by, among others, Edmund Burke, Charles Dickens, T.S. Eliot, Russell Kirk, J.R.R. Tolkien, Régine Pernoud and Gustave Thibon. A Senior fellow at the Russell Kirk Center for Cultural Renewal (a non-partisan, non-profit U.S. educational organization based in Mecosta, Michigan), he is also a founding member as well as a member of the Advisory Council of the Center for European Renewal (a non-profit, non-partisan pan-European educational organization based in The Hague, The Netherlands). A member of the Advisory Council of the European Federation for Freedom of Belief, in December 2022, the Universal Peace Federation bestowed on him, among others, the title of Ambassador of Peace. From February 2018 to December 2022, he has been the Editor-in-Chief of International Family News. He serves as Director-in-Charge of the academic publication The Journal of CESNUR and Bitter Winter: A Magazine on Religious Liberty and Human Rights.