The story of an extinct group, also called the “Three Periods of Pudu,” is taught to those in charge of fighting “cults” in China. But why is it still relevant?

by Massimo Introvigne

In November 2021, the story of a new religious movement that no longer exists, Greater China Buddhism (大中华佛国), was included in the material those fighting xie jiao in China should study. The Chinese machinery combating religious groups banned as xie jiao (sometimes translated as “evil cults,” while a better translation would be “heterodox teachings”) cannot be compared to the anti-cult movements in the West, not even to the governmental anti-cult agencies that exist in France and elsewhere. In China, the anti-xie-jiao effort involves tens of thousands of people, who operate in all provinces, cities, and towns.

The story of the Greater China Buddhism is probably regarded as relevant because the group exhibited what in a tradition dating back to Imperial China and the Middle Ages is believed to be a principal and even stereotypical feature of the xie jiao: they are hostile to the government and one may suspect that their ultimate aim is to replace the legitimate authorities with their leaders.

The area around the city of Xiangtan, in the Hunan province, has historically been rich of redemptive societies and salvationist sects. During the reign of the Guangxu Emperor (1875–1908), a landlord of the Xiangtan area called Shi Zengshun (石振顺) establishment a movement called the “Three Periods of Pudu,” a Taoist concept meaning “Universal Salvation.” This was the movement that would later be called “Greater China Buddhism.” Shi claimed that the third or final phase of Universal Salvation was coming, and produced a new sacred scripture called “15 Chapters on the History of Pudu in Its Third Phase” (三期普渡历史大概十五章).

Shi Zengshun also claimed to be a living Buddha, and gathered thousands of followers in Hunan and nearby provinces. Upon his death, Shi Zengshun was succeeded by his son Shi Huaizhen (石怀珍), who was in turn succeeded by his own son, Shi Dingwu (石顶武).

It was with Shi Dingwu (1924–1953) that the story of Greater China Buddhism starts interacting with larger political events. Shi Dingwu was a skilled organizer, and managed to gather some 30,000 followers, expanding the movement to several Chinese provinces. According to Chinese historians, he also closely aligned himself with the Kuomintang and opposed the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). In fact, CCP sources claim that leading figures of the Kuomintang army and intelligence services became members of the “Three Periods of Pudu.”

Be it for political reasons or because of his charisma, Shi Dingwu managed to build an impressive organization, with magnificent headquarters in Paitou Township, near Xiangtan, and other “palaces” in Changsha and Zhuzhou, also in Hunan province, and elsewhere. The Kuomintang registered the “Three Periods of Pudu” as a charitable organization, but Shi had more grandiose projects.

Shi proclaimed himself the new emperor of China, which was both a mystical title, signaling the advent of the third period of Universal Salvation, and a political one. Shi reigned from his imperial palace in Paitou Township, with his queen and three concubines, organized a government with ministers and departments, raised an imperial flag, proclaimed himself the head of “Greater China Buddhism,” the new name of his movement, and organized an army under the command of his follower Zhang Qifang (张启方).

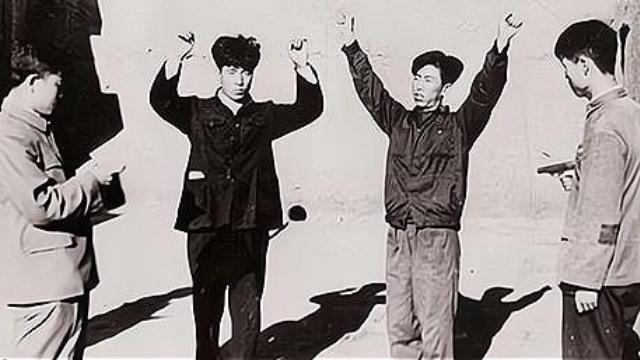

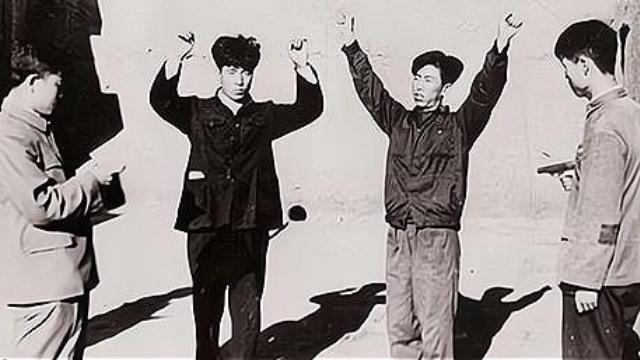

The army of the Greater China Buddhist Kingdom fought along the Kuomintang against the Communists in 1949, before Xiangtan fell to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in August 1949. Then, Shi Dingfu’s followers continued to harass the PLA in Hunan through guerilla warfare, which continued until the winter of 1952, when a PLA military operation led to the capture of the last partisans and of a significant arsenal of weapons. Shi and his queen escaped, and according to CCP sources were about to flee abroad, when they were arrested in June 1953.

In the winter of 1953, Shi Dingwu was executed at a public sentencing meeting attended by more than 10,000 people in Yisuhe town, Xiangtan county, Hunan province. Most followers who had been arrested signed letters of repentance, and were sent home after a period of reeducation.

However, some continued to meet clandestinely, and even managed to survive the Cultural Revolution. Among those who had been allegedly “reeducated” was the former “prime minister” of Shi Dingfu’s Greater China Buddhist Kingdom, Li Pirui (李丕瑞). In 1966, Li claimed he had received a dream asking him to reorganize Greater China Buddhism, but the time was not politically favorable, as it coincided with the beginning of the Cultural Revolution. Nonetheless, Li reorganized a viable network of devotees in Hunan and nearby provinces.

When the Cultural Revolution ended, Li believed the time had come to publicly restore the movement, and he went to Paitou Township where the son of Shi Dingwu, Shi Jinxin (石金鑫), was still living. Li arranged the marriage of Shi Jinxin with Zhong Yuexiang (锺月香), the daughter of an old associate of Shi Dingwu called Zhong Yuanren (钟源仁). The wedding was celebrated on October 25, 1981, and followers kneeled before Shi Jinxin, recognizing him as the new leader of the Greater China Buddhist Kingdom.

On October 21, 1983, Shi Jinxin was officially acknowledged as emperor, and appointed three prime ministers, Li Pirui, Li Zhenren (李臻仁), and Zeng Guangbo (曾广波). He also reorganized the Greater China Buddhist Kingdom army, although it did not have real military capabilities.

Unbeknownst to Shi and Li, the Public Security had already noticed and infiltrated the movement since 1979. On the morning of December 23, 1983, Li Zhenren was arrested by the police in Hongyuan township, Liling county, Hunan province. Subsequently, Li Pirui was arrested in Qingtanqiao village, Huangsha township, and Shi Jinxin was arrested in Liling county. Hundreds of other leaders and members were also arrested.

In 1984, the Zhuzhou City People’s Procuratorate committed 19 leaders of the movement to trial. In May 1985, the Zhuzhou City Intermediate People’s Court sentenced Li Pirui and Li Zhenren to death, and they were executed in the same year. Shi Jinxin, Zeng Guangbo and others escaped the death penalty, as it was believed they had been manipulated by Li Pirui and needed to be reeducated. Although rumors of resurgences of Greater China Buddhism periodically resurface, in fact the movement had been eradicated.

Why is this case included among the matters those fighting xie jiao today are supposed to study? In one way, it is proposed as a successful example of how to destroy a xie jiao by infiltrating it and arresting all the leaders. On the other hand, it is offered as evidence that xie jiao have as their ultimate aims to replace the legitimate political leaders of the country. From the Middle Ages, leaders of groups persecuted as xie jiao (a label first used in the 7th century CE) have always been accused of trying to proclaim themselves emperors—and some did.

Revisiting the story of Greater China Buddhism is both propaganda, aimed at proving that xie jiao are subversive (and slightly ridiculous), and a lesson on how the CCP can successfully fight them. Larger groups have, however, proved to be more resilient. And the way the story is told confirms that violence and executions are still believed by the CCP to be the best tools to deal with the “problem” of illegal religion.