The Tai Ji Men case and the persecution of the New Testament Church: how state control over religion has evolved—but not disappeared.

by Massimo Introvigne*

*Introduction to the session “Freedom of Religion Issues in Taiwan and the Tai Ji Men Case” of the CESNUR 2025 international conference, Cape Town, South Africa, November 19, 2025.

The Tai Ji Men case is one of Taiwan’s most enduring and perplexing human rights sagas. Before we delve into its details, I would like to offer a framing perspective. Not by starting with Tai Ji Men itself, but by looking back—back to a different time, a different spiritual movement, and a different kind of persecution. Sometimes, to understand the present, we must first revisit the past.

Let us travel to the 1970s, to a quiet hillside near Kaohsiung, where a Pentecostal Christian community known as the New Testament Church built its spiritual home: Mount Zion. Founded by the charismatic Hong Kong actress Mui Yee and later led by Elijah Hong, this movement was deeply millennialist, fervently communal, and—most importantly—politically nonconforming. That last trait, as history teaches us, is often the most dangerous.

During Taiwan’s Martial Law period (1949–1987), the Constitution’s promise of religious freedom was more decorative than functional. The ruling Kuomintang (KMT) regime viewed independent religious groups with suspicion. The New Testament Church, along with Yiguandao, Soka Gakkai, and several other groups, found itself in the crosshairs of a government that equated spiritual autonomy with political subversion.

In 1974, the government arbitrarily declared invalid the household registration certificates of residents of Mount Zion. Checkpoints were erected. Raids followed. Members were arrested. By 1980, the Supreme Administrative Court ruled that the registration certificates were, in fact, valid. But the damage had been done. Homes had been demolished. Property looted. Families scattered. The sanctuary—both physical and spiritual—had been desecrated.

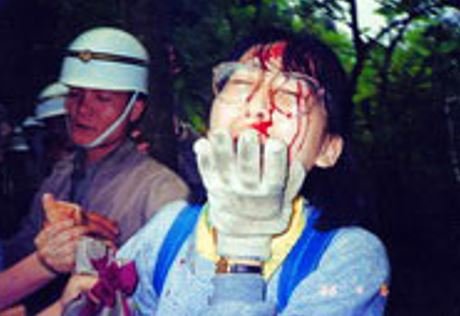

And it didn’t end there. In 1985, the reorganized communities of the New Testament Church were again attacked by police. This time, the violence was brutal. Beatings led to kidney bleeding, deafness, and even death. Only in 1987, under pressure from American Protestants and the U.S. government, was the church allowed to return to Mount Zion. Today, they preserve their story in a museum—a testament to resilience, but also a reminder of what unchecked state power can do to faith.

Why did I begin a session on Tai Ji Men with this tale of Christian persecution from decades ago? Because, while the times have changed, the underlying logic of repression has not.

Tai Ji Men is not a religion, but it teaches a spiritual path. And like Mount Zion, it is independent. It does not serve political agendas. It does not flatter power. And that, it seems, is still a problem.

The Tai Ji Men case began in 1996, nearly a decade after Martial Law was lifted. Taiwan was transitioning to democracy. The air was supposed to be freer. But old habits die hard. That year, a politically motivated crackdown targeted several religious and spiritual groups. Tai Ji Men was among them. Its leader, his wife, and two disciples were arrested. The Supreme Court eventually ruled in 2007 that Tai Ji Men had committed no crime. Case closed? Not quite.

Despite the ruling, the National Taxation Bureau continued to pursue fabricated tax claims. In 2020, it even seized and auctioned off sacred land belonging to Tai Ji Men. For nearly thirty years, the movement has been harassed through ill-founded tax bills. No physical beatings. No demolished homes. But a different kind of violence—bureaucratic, relentless, and corrosive.

So what connects Mount Zion and Tai Ji Men?

First, the idea that spiritual movements must align with the state, or suffer the consequences. During Martial Law, this meant overt violence. Today, it means legal harassment, reputational damage, and economic strangulation. The tools have changed. The mindset has not.

Second, both cases reveal a troubling elasticity in the application of law. In Mount Zion’s case, the government ignored the validity of household registrations until the courts intervened—too late. In Tai Ji Men’s case, the Supreme Court’s acquittal was ignored by the tax authorities, who continued their campaign as if the ruling had never happened. When law becomes optional, justice becomes elusive.

Third, both movements were punished not for what they did, but for what they represented: autonomy, conscience, and the refusal to be co-opted. In authoritarian systems, and sometimes even in post-authoritarian ones, these are dangerous virtues.

The physical violence inflicted on Mount Zion was horrific. Lives were lost. Bodies broken. Tai Ji Men has not suffered that scale of brutality.. But the absence of blood does not mean the absence of harm. To harass a peaceful movement for three decades through unjust tax claims is to inflict a slow, grinding violence—one that erodes trust, dignity, and the very fabric of civil society.

In fact, even in the Tai Ji Men case, physical violence was not absent. The initial arrests were harsh and unjust. Protesters have been mistreated. The state’s hand, while more gloved than in the past, still knows how to squeeze.

The Tai Ji Men case is not an isolated anomaly, but is part of a longer continuum of state-religion relations in Taiwan. A continuum that stretches from the barbed checkpoints of Mount Zion to the auction blocks of Tai Ji Men’s sacred land.

The story of Mount Zion is not just a historical footnote. It is a mirror of unresolved tensions between spiritual freedom and state control. We observe the persistence of a belief that conscience must be managed, autonomy must be punished, and peace must be conditional.

But we also see something else: resilience. The New Testament Church still exists. Tai Ji Men still exists, continues to flourish, and continues to grow. Both have turned suffering into testimony, persecution into perseverance.

And that, perhaps, is the most important lesson. Even in the face of injustice, spiritual movements persist. They adapt. They resist. And they remind us that the human spirit, when rooted in conscience, is not so easily broken.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.