Who is afraid of the church founded in 1926? Religious competitors, apostate and schismatic ex-members, and those who fear its social influence.

by Rosita Šorytė*

*A paper presented at the CESNUR 2025 conference, Cape Town, South Africa, November 18, 2025

It is a privilege to join you today in celebrating the centenary of La Luz del Mundo—a church that, despite formidable opposition, has endured, grown, and inspired millions. Yet, few religious movements have faced the sustained, multifaceted opposition that La Luz del Mundo has endured.

I will not comment on the legal situation of the church’s Apostle, who is currently incarcerated on charges of sexual abuse, although millions of members believe in his innocence. What concerns me—and what should concern all of us—is the slander directed at ordinary members of the church. These are people who are not accused of any crime, yet they are vilified in the media, ostracized in their communities, and treated as if their faith were a stain rather than a source of strength.

Even the Apostle’s elderly mother, a woman revered within the church for her piety and charitable work, has been arrested on vague charges. The stories fueling this wave of hostility often come from a handful of apostate ex-members—individuals who, for reasons personal or political, have chosen to rewrite the church’s history. And what a history it is: a century marked not only by phenomenal growth but by massive charitable endeavors, educational initiatives, and social upliftment in Mexico and beyond.

Who are the enemies of La Luz del Mundo? Why such venom? Why this unprecedented hostility?

Traditionally, members of the church point to their old adversary, the Catholic Church. And yes, there is history there. But I suspect the answer is more complex. Since our theme today is the centenary, we may revisit the church’s origins and the early resistance faced by its founder, Aarón, to understand today’s opposition.

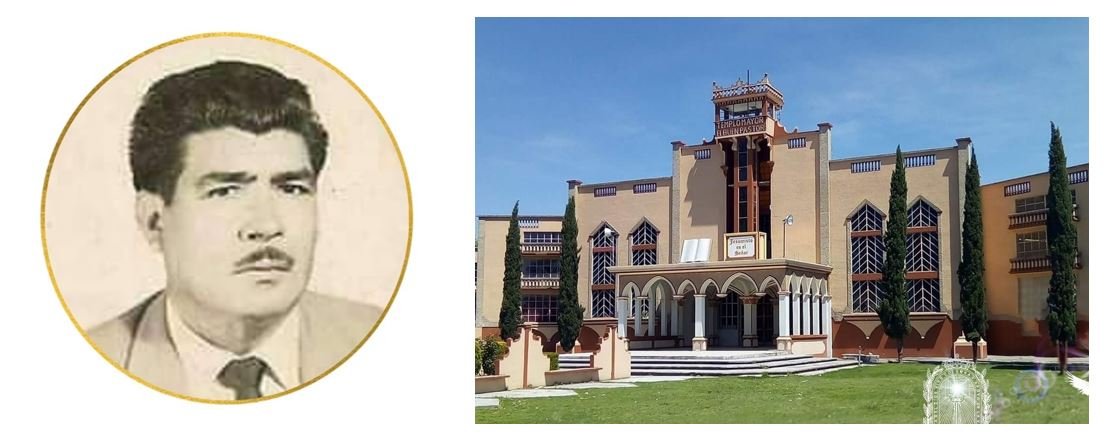

La Luz del Mundo was born during the Mexican Revolution—a time of upheaval, idealism, and ideological realignment. Most religious institutions in Mexico, including the Catholic Church and many Protestant denominations, clung to conservatism. Aarón’s church, by contrast, embraced modernization and the revolutionary ideals of social justice. It was Protestant, but unlike most Protestant churches in Mexico, it was not an American import. It was founded by a moreno Mexican, Eusebio Joaquín González, later known as Aarón, rather than by foreign missionaries.

This made it a target. Catholics saw it as heretical. Mainline Protestants saw it as competition. And both spread a lie that still haunts the church: that La Luz del Mundo was a political creation, a puppet of anticlerical President Plutarco Elías Calles, designed to harass the Catholic Church.

No scholar who has studied the church believes this theory. During the presidencies of Calles and Cárdenas, Aarón and his followers were poor—painfully so. While other Protestant groups received confiscated Catholic churches, La Luz del Mundo received nothing. If anything, the authorities looked suspiciously at Aarón’s ragtag congregation, occasionally harassing them. The idea, repeated today, that Aarón was guilty of immorality but protected because of his connection with President Calles, is absurd.

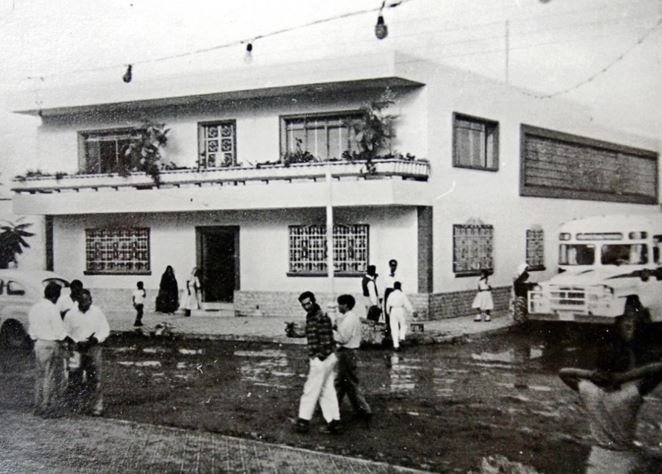

It is doubtful that Calles even knew of La Luz del Mundo during his time in office. Later, some local politicians in Guadalajara did speak favorably of the early church—not to win votes, but because they saw its impact. Members in their Hermosa Provincia settlement avoided alcohol, promoted education, and lifted themselves out of poverty. They were, in short, model citizens.

Yet the rumors persisted. As the church grew, so did its internal tensions. Schisms are the shadow side of success.

The largest schism came in 1942, led by José María González, once Aarón’s close ally. González claimed divine revelation had led him to found a new church called El Buen Pastor, The Good Shepherd. The breaking point was Aarón’s birthday celebration. González believed Christians should not celebrate birthdays. Scholars, however, point to personality clashes as the real cause.

El Buen Pastor, with its own Santa Cena and temple in San Pedro Totoltepec, is today a miniature version of La Luz del Mundo, with around 11,000 members. But in 1942, it was a severe blow. Aarón lost 25% of his followers, including most in Mexico City.

Worse, the schismatics had better media and political connections. They insisted on false rumors of immorality and persuaded the authorities to shut down the Luz del Mundo temple—though it was soon reopened. Unfortunately, their accusations echo to this day. This incident confirmed that La Luz del Mundo, guided by Aarón, was persecuted rather than protected by the media and politicians.

So, as it often happens with new religious movements, we had two categories of opponents spreading slander and falsehoods: religious rivals—Catholic and Protestant—and schismatic and apostate ex-members. But there is a third, more elusive force.

Through its educational and charitable work, La Luz del Mundo has empowered millions—especially women and the poor—to live autonomous lives, challenge societal norms, and think for themselves. This is dangerous—not to the devotees but to those who prefer a compliant populace. There are always political and social forces that fear independence. They operate in shadows, and identifying them would require resources and research. But their fingerprints are there.

Sometimes, political leaders are criticized not for what they do wrong but for what they do right. They educate their citizens, improve the economy, and promote civic engagement—yet they are accused of undermining stability because they challenge a certain status quo. La Luz del Mundo does the same—spiritually and socially.

Yet history teaches us that these opposing forces are powerful but not invincible. They may destroy individuals but not ideas. Many predicted the church’s collapse after the Apostle’s arrest in 2019. It did not happen. Even critics grudgingly admit that La Luz del Mundo continues to grow.

It does so because of its human and social capital. I have studied its charitable work: hospitals, schools, and aid programs serving members and non-members. Whatever one may think of the accused leaders, nothing can erase the good done by thousands of volunteers. They have helped women, immigrants, the sick, and the elderly. Tens of thousands remain grateful. That gratitude is not easily undone.

Resilience is the quiet strength of endangered nations, as we see today in Ukraine. In religion, it is the serene strength of faith. La Luz del Mundo has both. It has survived poverty, persecution, schism, and slander. It has built temples, schools, and communities. It has lifted people out of despair and into dignity.

As we mark a century of La Luz del Mundo, we remember that opposition is not new. It began with Aarón. It came from religious rivals, schismatics, and shadowy forces. But the church endured, grew, and continues to serve.

I believe that this resilience, this commitment to service, and this deep-rooted faith will carry La Luz del Mundo far beyond the present crisis. As a church, it offers its members a community that is a testament to the enduring power of belief.

Rosita Šorytė was born on September 2, 1965 in Lithuania. In 1988, she graduated from the University of Vilnius in French Language and Literature. In 1994, she got her diploma in international relations from the Institut International d’Administration Publique in Paris.

In 1992, Rosita Šorytė joined the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Lithuania. She has been posted to the Permanent Mission of Lithuania to UNESCO (Paris, 1994-1996), to the Permanent Mission of Lithuania to the Council of Europe (Strasbourg, 1996-1998), and was Minister Counselor at the Permanent Mission of Lithuania to the United Nations in 2014-2017, where she had already worked in 2003-2006. In 2011, she worked as the representative of the Lithuanian Chairmanship of the OSCE (Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe) at the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (Warsaw). In 2013, she chaired the European Union Working Group on Humanitarian Aid on behalf of the Lithuanian pro tempore presidency of the European Union. As a diplomat, she specialized in disarmament, humanitarian aid and peacekeeping issues, with a special interest in the Middle East and religious persecution and discrimination in the area. She also served in elections observation missions in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Belarus, Burundi, and Senegal.

Her personal interests, outside of international relations and humanitarian aid, include spirituality, world religions, and art. She takes a special interest in refugees escaping their countries due to religious persecution and is co-founder and President of ORLIR, the International Observatory of Religious Liberty of Refugees. She is the author, inter alia, of “Religious Persecution, Refugees, and Right of Asylum,” The Journal of CESNUR, 2(1), 2018, 78–99.

Languages (fluent): Lithuanian, English, French, Russian.