Some try to persuade us that the French 16th-century astrologer predicted World War III and widespread religious persecution. A look at the “Nostradamologists.”

by Massimo Introvigne

Will the events in Ukraine trigger a World War III? Yes, some prophecy buffs tell us, based on predictions by Michel de Nostredame, the French astrologer still known today by the Latinized name of Nostradamus (1503–1566). Some may even find here an opportunity to make some money. The publicity on Amazon for an old book on Nostradamus’ and other prophecies has been quickly updated to state that “The current and gathering crisis pitting the United States and the European Union against the Russian Federation over Ukraine may have rewound the doomsday clock and started it ticking out… That time is today.”

But did Nostradamus really predict that World War III is now at hand and will start in Ukraine? Those who answer yes point out to several predictions about devastating wars (yet to come) and a conflict between “three kings,” whom they identify in Putin, Biden, and NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg (perhaps because the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, is a “queen,” a woman). Of course, none of these characters is really a king.

The “Prophecies” of Nostradamus are divided into “centuries,” and in the eighth one we find references to “three kings” and also to “three brothers.” That “brothers” and “kings” are the same is already a matter of interpretation. We read in 8:17 that “Par les trois frères le monde mis en trouble. Cité marine saisiront ennemis. Fain, feu, sang, peste, et de tous maux le double,” “Through the three brothers the world will get into trouble. The enemies will take a maritime city. Hunger, fire, blood, plague, and a double dose of all disasters.”

The “maritime city” would be Odessa, Ukraine, taken by the Russians, and the “double dose of all disasters” (including a new outbreak of the “plague,” identified with COVID-19) is interpreted as World War III. Of interest to readers of Bitter Winter, Nostradamus there also predicts widespread, religious persecution that would even compel the Vatican to “move to another place.”

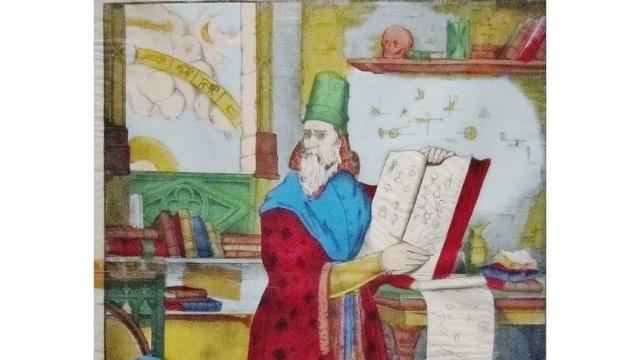

This interpretation, however, points to general problems about Nostradamus. Many have heard his name; few really know anything about him. Michel de Nostredame was an esteemed physician, who became advisor to the French Kings Henry II (1519–1559) and Charles IX (1550–1574). Passionate about astrology, starting in 1555 he published his “Centuries,” each composed of one hundred quatrains, except the seventh, which includes only 42.

In 1559, one of these was read as an exact prediction of the death of King Henry II for the consequences of a wound he received during a jousting match, and the doctor-astrologer became very famous. Even the prediction of his own death “on his return from an embassy, near a bed and a bench (banc)” seemed to come true. Nostradamus died at home on the night of July 1, 1566, he was returning from having represented his city, Salon-de-Provence, in Arles, and although he had no bench in his room, he used a “bench” (banc) to climb on his bed.

Everything else is much more uncertain. He is supposed to have prophesied the French Revolution, World War II, and many other events. But to believe it you should lend faith to this or that “Nostradamologist,” who offers interpretations of the quatrains, which in themselves are rather obscure and open to a plurality of different meanings.

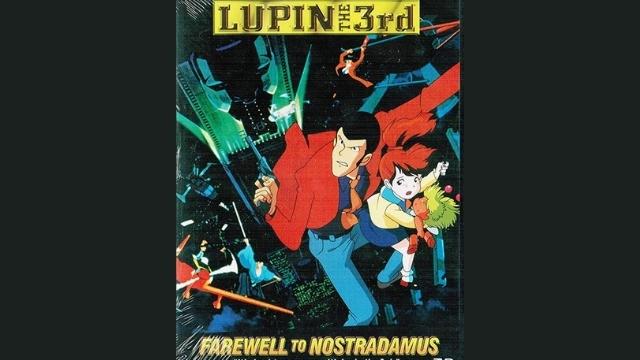

Today there is only an embarrassment of choice. Thousands of Internet sites, hundreds of books, magazines, movies, and even cartoons and comics are dedicated to Nostradamus. The latter come often from Japan, the country where the Nostradamus craze is strongest. The Provençal seer is the subject of a much more copious literary production in Japan than in his native France. There are, by now, many different Nostradamus: and a map is necessary to orient oneself.

First, there is the academic Nostradamus. A few academic-level historical studies of Nostradamus do exist. There is, however, a difference between specialists of sixteenth-century history and local scholars of Provence, on the one hand, and academics who are themselves enthusiasts of esotericism or who approach Nostradamus with curiosity coming from different fields of study.

The two parties confronted each other at several conferences in Salon-de-Provence, the city where Nostradamus died and which hosts a museum dedicated to him. From these conferences emerged in 1992 the volume edited by Robert Amadou (1924–2006) L’astrologie de Nostradamus (Poissy: ARRC). It remains an important reference, although Amadou was a typical scholar-cum-esotericist.

Historians urge that Nostradamus be read as a character of his own century. They believe that most of his predictions had precise references to characters and events of his era, which may easily escape the modern reader. Some esotericists and scholars from other fields, including philologist Georges Dumézil (1898–1986), on the other hand, believe that Nostradamus represents a genuine case of prediction of the future through astrology.

Second, there is a Nostradamus of magicians. Professional soothsayers and psychics, not to be confused with scholars of esotericism, often use Nostradamus to predict in detail their clients’ future and even the broader future of politics and economy. Every time an international crisis breaks out, there is also a battle among magicians, each of whom claims that “I interpret Nostradamus better than anyone else.” The claims sometimes border on the ridiculous but delight a certain popular press.

Until 2014, when she died, prominent in these battles was Dolores Cannon (1931–2014), a hypnologist from Arkansas who claimed not to need interpretations because, through her hypnotized patients, the spirit of Nostradamus himself explained the Centuries to her.

Third, the skeptics’ Nostradamus. In a difficult battle against the believers and the gullible, the professional skeptics and apologists for modern science try to convince us that Nostradamus never got anything right. Their bible is the book where Nostradamus was demolished as a charlatan by the stage magician and “professional skeptic” James Randi (1928–2020: The Mask of Nostradamus, Buffalo: Prometheus Books, 1993). Their followers, in these postmodern times of the return of the marvelous, are not that many.

Fourth, let’s not forget the Catholic Nostradamus. An old book, constantly reprinted and still popular in circles interested in Marian apparitions and private revelations, was written by Raoul Auclair (1906–1997), who in his old age joined the Canadian new religious movement Army of Mary. Auclair’s book Les Centuries de Nostradamus ou le dixième Livre Sibyllin (Paris: Nouvelles Éditions Latines, 1975) combined Nostradamus with the Marian apparitions of Fatima and La Salette, and various Catholic prophecies of 19th-century France.

The historical reconstruction was adventurous, but perhaps Nostradamus would not have protested. His orthodoxy might have been dubious but he wanted to call himself a Catholic, and the Church put his prophecies on its Index of forbidden books only in 1781.

Fifth, there is the commercial Nostradamus. Both in the United States and in Japan there have been attempts at copyrighting the image, or one image, often derived from comics, of Nostradamus and sell it for commercial purposes. Some of these ventures fared quite well.

There is also a sixth, anticlerical Nostradamus, a more recent invention of German novelist Manfred Böckl. He claimed that the Centuries should be read as metaphors cleverly hiding, to escape prosecution, a denunciation of the evil and even Satanic character of the Catholic clergy and the French aristocrats who supported the Church. In fact, however, bishops and aristocrats were Nostradamus’ most generous patrons.

The seventh, more interesting, character is the Nostradamus of the new religious movements. Shoko Asahara (1955–2018), the leader of the Japanese movement Aum Shinrikyo, who was executed in 2018 for the nerve gas attack in the Tokyo subway in March 1995, did not base his apocalyptic predictions on the end of the world only on esoteric Buddhism.

He had a public controversy, followed at that time with great interest in Japan, with Ryuho Okawa, the leader of another Japanese new religion, Kofuku no Kagaku. Both of them believed Nostradamus, correctly interpreted, supported their claims. Nostradamus or not, to his credit Okawa also predicted that Asahara would be implicated in criminal activities and would not end up well. Of course, mobilizing Nostradamus on behalf of the claims of new religious movements does not happen in Japan only.

Who is right? The question is misplaced. By its nature, the text of Nostradamus lends itself to the game that Umberto Eco (1932–2016) called the “infinite interpretation.” It is a game where interpretation is much more important than any original reality of the text. Perhaps here lies the most interesting aspect of Nostradamus. All interpret him as they wish, and he regularly comes back into fashion whenever events make anxieties about the future stronger. Of course, scholars can search for a “Nostradamus of history.” But in the collective imagination today, Nostradamus is not so much a historical figure. He is a cultural icon, a mirror that reflects our anxieties and magnifies our fears.