President Trump’s remarks have sparked an international controversy, lacking nuance and full of misunderstandings.

by Massimo Introvigne

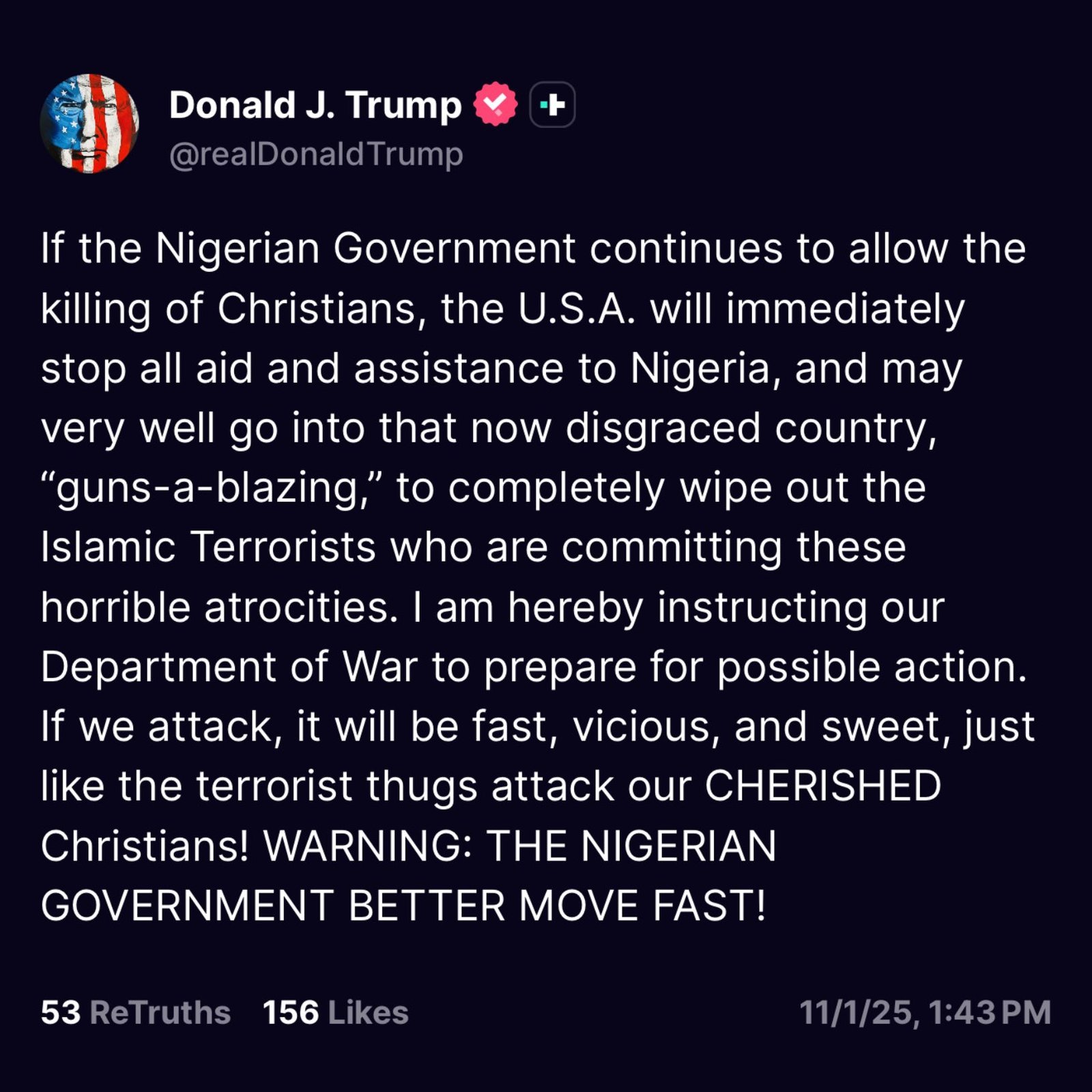

When Donald Trump threatened military intervention to stop the killing of Christians in Nigeria, the world gasped—some in horror, others in hope. Was this a reckless geopolitical provocation or a long-overdue spotlight on a crisis that has simmered for years?

The answer, as with most things Nigerian, is not simple. Yes, Christians are being killed. Yes, Muslims are also victims. And yes, the violence is religious, political, ethnic, and environmental—all at once.

The Vatican-sponsored Aid to the Church in Need (ACN) paints a harrowing picture in its authoritative 2025 report on religious liberty. “Nigeria witnessed a surge in religiously motivated violence between January 2023 and December 2024, particularly in the North and the Middle Belt,” the report explains. “Armed groups such as Boko Haram, the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), and various militias carried out large-scale attacks on churches, villages, and religious leaders. In Plateau and Benue States, thousands were displaced and hundreds killed, including more than 1,100 Christians—among them 20 clergy—in just one month following the 2023 presidential inauguration. During Christmas 2023, coordinated attacks by local and foreign militants left nearly 300 dead. In June 2025, around 200 displaced Christians were massacred in Benue.”

These are not isolated incidents. ACN concludes that “the Middle Belt incidents are not random attacks, but rather part of a campaign of ethnic and religious cleansing.” The report notes that “radicalised Fulani herdsmen continue to be implicated in attacks against Christian communities, often involving land seizures and displacement.”

The Fulani dimension is especially thorny. ACN acknowledges that their grievances are multifaceted—rooted in identity, marginalization, and environmental stress.

This duality is crucial. While some Church leaders describe Fulani violence as a deliberate strategy to expel Christian populations, others caution against painting all Fulani with the same brush. The report itself includes a backgrounder on the Fulani, suggesting that extremist ideologies have hijacked ethnic tensions for broader political aims.

Within the Catholic Church, reactions to Trump’s statement have ranged from enthusiastic to skeptical. Bishop Matthew Kukah of Sokoto, a respected voice for interfaith dialogue, has raised doubts about the framing of the crisis as religious persecution. He insists that “coexistence between Muslims and Christians is possible” and warns that external pressure could undermine local peace efforts. Cardinal Pietro Parolin, the Vatican Secretary of State, added a layer of nuance: “There is not a religious conflict, but rather more a social one, for example, disputes between herders and farmers.” He also emphasizes that “many Muslims in Nigeria are themselves victims of this same intolerance.” Yet, some Nigerian Catholics welcomed Trump’s intervention, seeing it as a long-overdue recognition of a crisis that had been largely ignored.

As a sociologist, I would add that scholars agree that there is no such thing as a purely religious persecution. The Roman Empire did not execute Christians because it disliked the Eucharist—it feared their refusal to worship Caesar would fracture imperial unity. Similarly, Nigeria’s violence is a tangled web of religious extremism, ethnic identity, political dysfunction, and environmental collapse.

Yes, Muslim radicals kill Muslims too, and yes, Christians are disproportionately targeted. These truths coexist. Recognizing the complexity doesn’t dilute the urgency—it sharpens it.

Christians are being killed in the thousands. That’s not up for debate, although statistics are. The violence is not only religious. It’s also political, ethnic, and environmental. Muslims are victims too. Extremist groups make no distinction. Whether through diplomacy, aid, or advocacy, the international community must respond.

Trump’s threat of military intervention may sound theatrical, but it has forced global attention on a crisis that many prefer to ignore. His style is divisive, but his spotlight has stirred uncomfortable conversations and perhaps nudged international actors toward action.

In the end, the question isn’t whether Christians are persecuted in Nigeria. They are. The real question is how to respond. And that requires more than tweets and troops—it demands truth, nuance, and solidarity.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.