Government and courts, influenced by extremists, continue to discriminate against the Ahmadi minority.

by Lord David Alton

Since it emerged as a nation-state on 14 August 1947, Pakistan has been a country that has had religious freedom enshrined at the heart of its constitution. Indeed, Part II of Pakistan’s constitution (2.20, a-b) clearly highlights a right to religious liberty—including for denominations within a faith—stating: “(a) every citizen shall have the right to profess, practice and propagate his religion; and (b) every religious denomination and every sect thereof shall have the right to establish, maintain and manage its religious institutions.”

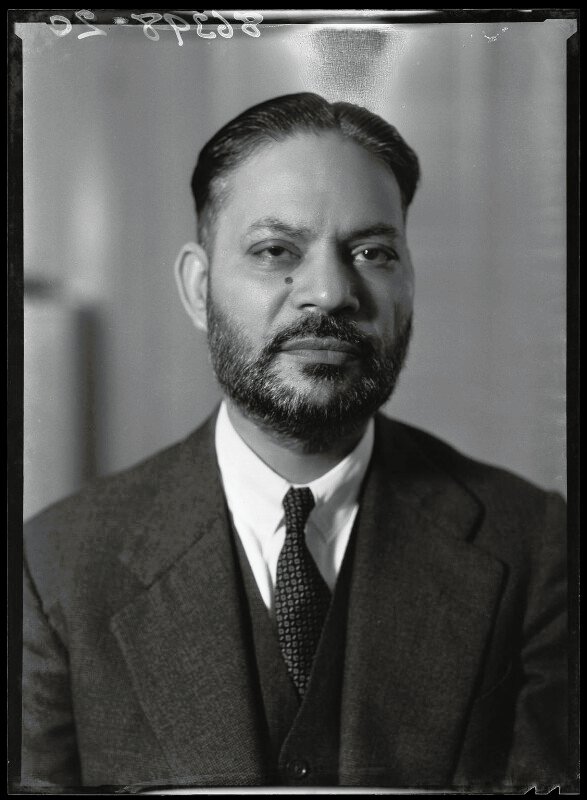

Religious freedom was also the apparent desire of its founder, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who in a speech in 1947 stated that “you are free; you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other places of worship in this State of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion or caste or creed—that has nothing to do with the business of the State.”

Muhammed Ali Jinnah died on 11 September 1948. After his death, there had been a steep erosion of the right to freedom of religion or belief. Today, in the contemporary political legal environment, Pakistan’s Ahmadi Muslim community is still extremely vulnerable, and their fundamental human rights are consistently violated.

This article will explore both legal and judicial threats that have emerged against the religious freedom of Pakistani Ahmadi Muslims in recent years.

The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community believe in the revival of Islam as brought about through Mirza Ghulam Ahmad of Qadian, whom they believe to be the Promised Messiah and a prophet who came to revive the faith of Islam. As a result, they have faced charges of blasphemy, and, in Pakistan, such laws have extended to the provincial and national level—a process that started under the premiership of Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in the 1970s. Most notably, the Second Amendment to the Pakistani constitution (article 260) meant that Ahmadi Muslims were classified as non-Muslims.

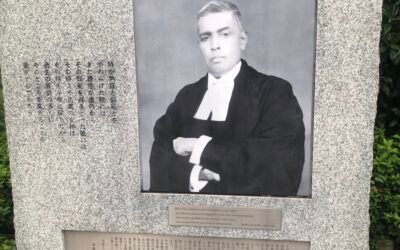

For a country founded as an Islamic Republic and where Ahmadi Muslims such as Sir Muhammad Zafarullah Khan, who was the country’s first Foreign Minister and who played a critical role in its creation, this came as a major blow, and it started the political process of their “othering” from society. It also served as an early example of the threat posed by extremist clerics to the country’s tolerant foundations.

In 1984, this legal persecution deepened under the military dictatorship of General Zia-ul-Haq, who through his plan for the “Islamization of Pakistan” introduced explicit penalties for Ahmadi Muslims for posing as Muslims. In Ordinance XX, which introduced sections 298-B and 298-C in Pakistan’s Penal Code, the law states that any Ahmadi Muslim who “directly or indirectly poses” as a Muslim “shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to three years and shall also be liable to fine” (Pakistan Penal Code, 298-C).

It was a pivotal and landmark moment, as this law translated existing anti-Ahmadi hatred into criminal penalties and marked a major shift in Pakistan’s journey towards legal injustice. No surprise then that as early as 1987, legal scholars identified the dire discriminatory effect of Ordinance XX in the Pakistani context, noting that “language and enforcement procedures of Ordinance XX violate general principles of law under both derogation standards. The terms of Ordinance XX are undefined, overbroad, and discriminatory solely on the basis of religion” (Berberian, L.J., 1986, “Pakistan Ordinance XX of 1984: International Implications on Human Rights,” Loy LA Int’l & Comp LJ, 9, p. 668).

These developments created an unusual paradox within Pakistan’s legal system. On the one hand the core of Pakistan’s early constitutional text highlighted individual freedoms, particularly when it comes to religion, as has been corroborated by the words and actions of Pakistan’s founder. On the other hand, new laws formulated since the 1970s run completely contradictory to these principles, particularly for Ahmadi Muslims.

It would be fair to say that this unusual legal situation has now reached a breaking point for Ahmadi Muslims in Pakistan who can no longer trust the country’s deep rooted constitutional provisions of freedom of religion to protect them. This is especially true considering extremist movements such as the Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP), a far-right religious extremist organisation, that has targeted and killed Ahmadi Muslims in recent years.

The contradictory legal situation has been further exacerbated by the state of Pakistan’s judicial system, which has shown little ability to challenge unjust laws that undermine its constitutional commitment to freedom of religion and belief. In fact, in the overwhelming number of instances not only has the judicial system has failed to uphold justice for those “convicted” of such so-called crimes but also the judiciary itself has—in many cases—been complicit in fostering the hostile anti-Ahmadi environment in Pakistan, albeit under pressure from extremist clerics. A clear example of this came in the 2024 Mubarak Sani case, which represented a new low in the persecution of Ahmadi Muslims.

Here, Sani was arrested in January 2023 for allegedly distributing a “proscribed copy” of the Holy Quran in 2019. In February 2024, the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Faez Isa accepted the post-arrest bail application of Sani, and his petition for the amendment of criminal charges in the police’s original First Information Report (FIR) thereby dropping all the criminal charges. It stated that criminal charges and imprisonment were not lawful as firstly, Sani has completed the prison term if he would have been tried under the concerning law and secondly, the criminal charges leveled against him were either unrelated to the alleged offenses committed or that they were not a criminal offence at the time the said incident took place. Put simply, Sani could not be charged with a crime if the action was not a crime at the time. Crucially, the court also affirmed in passing in its judgement that Ahmadis had the constitutional right to privately practice their faith.

This sparked a fierce backlash from extremist groups, particularly the TLP, which leveraged the decision to organize large-scale protests—some of which turned violent. The group also launched a hate campaign against the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, and a 10 million Pakistani rupee bounty was put on his head. In July 2024, bowing to clerical pressure, the Supreme Court agreed to review the ruling in response to petitions from the Punjab Government and various Islamist organisations.

The Supreme Court then released a supplemental judgment in July 2024. This “clarification” emphasized that the Court’s original February 2024 ruling only addressed retroactive punishment and did not extend broader protections to the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, reflecting the Court’s response to—and a clear reaction to—pressure from hardline groups like TLP. While the revised text reiterated that religious freedom is constitutionally guaranteed but bounded by law, morality, and public order, it also stated that Ahmadi Muslims may practice and propagate their faith only if they refrain from using Islamic terms or publicly identifying themselves as Muslims. These statements provoked another round of protests and threats aimed at the judiciary, fueling more demands that the Supreme Court revise its stance.

Under pressure from influential religious scholars and leaders, the Supreme Court of Pakistan responded to the plea by the Federal Government in August 2024, which insisted that language viewed as granting undue concessions to the Ahmadiyya Muslim community be removed. On 22 August 2024, the Supreme Court, shockingly, acceded to these demands, striking specific sections from the judgment that referenced constitutional freedoms for Ahmadis.

By reversing course under political duress, the Supreme Court signaled a troubling trend: its willingness to amend legal decisions under the influence of powerful extremist voices. This move not only undermined the Court’s perceived independence and eroded public trust in its authority but also emboldened groups seeking to impose stringent religious standards on state policy.

Pakistan’s actions today continue to deepen both legal and judicial injustices. With growing awareness internationally, these injustices have been heavily criticized by NGOs and governments alike.

For instance, in a September 2023 Parliamentary debate, British MP Fleur Anderson highlighted the problem of judicial injustice, noting that Ahmadi Muslims “cannot turn to the justice system either. Fifty Ahmadi Muslims are currently in prison solely on account of their faith. Eid festival celebrations this year led to massive police raids to the homes of Ahmadi people who were just practicing their faith, with 12 Ahmadis arrested for visiting family and friends to take part in the celebrations.”

Criticisms were likewise echoed by Amnesty International, who called on the Pakistani authorities to “end the growing attacks on Ahmadis. They must respect, protect, promote, and fulfill the human rights of the members of the community.”

Similarly, the US State Department designated Pakistan a “Country of Particular Concern” for religious freedom, a term that highlights that “particularly severe violations of religious freedom” have taken place.

All this attests to the poor state of religious freedom in the country today. Those with responsibility for Pakistan’s future should reflect that those countries that uphold religious freedom are the most prosperous and stable nations and those that do not are the poorest economically and are often the most unstable.

It is ironic that Pakistan’s founder Muhammad Ali Jinnah was a renowned lawyer with an acute sense of justice for all. He founded a country that was to be a torchbearer of religious freedom and where justice would prevail. Wise leaders would urgently revive that vision and make it a reality for all its citizens.

Lord David Alton is a longstanding member of the UK Parliament, having served both Houses, and is Chair of the UK Parliament Joint Committee on Human Rights. He is also a Vice-Chair of the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Freedom of Religion and Belief and member of the All-Party Parliamentary Group for the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. He writes for “Bitter Winter” in his personal capacity.