All Chinese should study the history of the CCP for its 100th anniversary. However, the Party’s first General Secretary should not be mentioned.

by Ye Wangfang

Every Chinese knows that 2021 marks the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). President Xi Jinping has launched a great campaign compelling all citizens to diligently study the history of the Party.

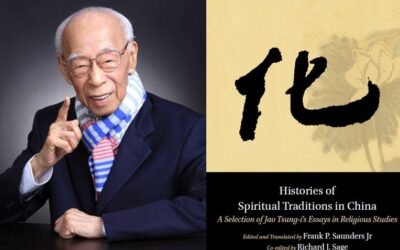

Edited Party history, that is. The CCP has had only 11 (or 12, if you consider Wang Ming’s short rule in 1932) General Secretaries in 100 years. A foreigner may assume that the first General Secretary is celebrated as a great hero, and is a household name in China. This is not the case. His name has been erased from most official Party histories. It is known to academic scholars, but almost unknown to the general population.

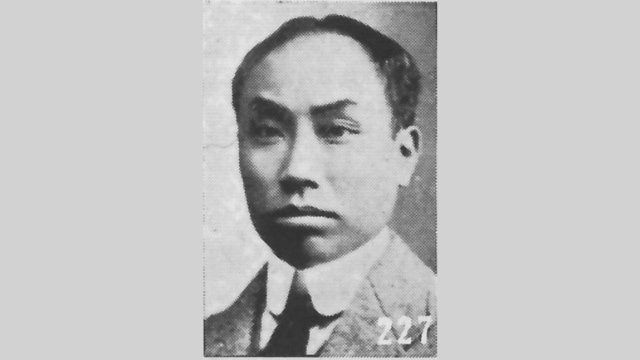

The forbidden name is Chen Duxiu. He was born in Anqing, a prefecture-level city in Anhui province, in 1879. Although he found the system of imperial examinations corrupted, he passed them both at the county and provincial level in 1896 and 1897. He then studied at Hangzhou’s Qiushi Academy and in Japan at the military preparatory school Tokyo Shimbu Gakko. He was exposed to Socialist ideas, and by the time he returned to China, he had become a progressive politician, which compelled him to escape repeatedly to Japan.

In 1915, Chen founded the journal “Youth,” later renamed “New Youth.” In 1917, he became a professor at Peking University. “New Youth” included the most detailed presentations of Marxism available in China at that time, which led to Chen’s expulsion from the university in 1919.

In 1921, Chen and his co-worker at “New Youth,” Li Dazhao, founded the Chinese Communist Party, stating that their models were Lenin and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. They called for a “national” congress, which was attended in Shanghai on July 23, 1921, by thirteen delegates only, one of whom was the future Chairman Mao who represented the Communists of the province of Hunan. Chen was elected General Secretary, and at that time was certainly a figure more prominent than Mao in the Party.

In 1925, an ideological quarrel developed between Mao and Chen. The latter believed that factory workers will be the main force for the success of Communism in China, while Mao regarded the peasants as more important. Chen also believed that some bourgeois institutions, such as an independent judiciary, will survive and may play a positive role in Communist China.

Stalin sided with Mao, perhaps because he regarded the latter as a more promising leader. Eventually, this led Chen to criticize Stalin and align himself with Stalin’s opponent within the international Communist movement, Leon Trotsky. In 1927, Chen lost his position as General Secretary of the CCP, and in 1929 was expelled as a Trotskyist.

In 1932, Chen was arrested by the Nationalists, who later released him hoping he would cooperate with Chiang Kai-shek. Being a true believer in Marxism, Chen refused and tried, unsuccessfully, to be readmitted into the CCP.

Instead, in 1938 he was denounced by the CCP as a “Trotskyist bandit” and (falsely) as an agent on the payroll of the Japanese. Later, the future Chinese Prime Minister Chou Enlai attempted a reconciliation, but asked Chen to sign a self-criticism document admitting his crimes, which he refused. He continued to criticize Stalin in the following years.

In his old age, Chen and his wife lived in poverty 30 miles from downtown Chongqing, then part of Sichuan province. His wife, Pan Lanzhen, had to pawn her jewelry, and they survived by planting and eating potatoes. Chen died in 1942, at the age of 62.

Mao held Chen in high esteem at the time of the founding of the CCP, but later branded him as the chief culprit of the early defeats of the Party, “a traitor,” “a foreign agent,” a “counter-revolutionary,” and a “class enemy.” American pro-CCP journalist Edgar Snow popularized the view that all the early mistakes of the CCP should be attributed to Chen, and all the achievements to Mao.

Chen was subsequently erased from CCP’s history. Only in the 21st century, some Chinese academic historians tried to rehabilitate Chen, but their works were not endorsed by the Party.

How the CCP treated, or mistreated, its own co-founder and first General Secretary, is evidence of the old saying that “like Saturn, the Revolution devours its children.” It also proves that the CCP’s edited version of the history of the CCP cannot be trusted.

Uses a pseudonym for security reasons.