Xi Jinping was unanimously re-elected with 2,952 votes. But censors suspect that “2,952” is now a code word used to poke fun at the Chinese pseudo-democracy.

by Tan Liwei

Last week, netizens in China started making a surprising discovery. They could not search “2952” through Chinese search engines (Google is banned in China) or social media. At first, they believed it was a technical problem. They tried other numbers. They worked. Even 2951 or 2953 were searchable. But not 2952.

It was a show of effectiveness of the Chinese censorship, but at the same time it demonstrated the paranoia and fear of any criticism by the regime or perhaps Xi Jinping himself.

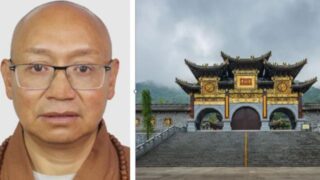

Xi was re-elected as President of China on March 10. The results of the vote were: favorable, 2,952: contrary, zero; abstained, zero. In the following hours, “2952,” often posted without comments, became a way for the oppressed Chinese netizens to poke fun at China’s pseudo-democracy, without posting criticism or sentences that may land them in jail.

This was annoying for a President whose agenda prominently includes putting an end to what he calls the “Internet chaos” and eradicate any criticism of the CCP from the web. Almost immediately, searches for “2952” were blocked. Those who tried them received a message that “According to the relevant laws, regulations and policies, the page is not found”—an elegant formula to indicate that the search engine was capable of performing its job but was prevented from doing it by the law.

The censors’ work was just beginning. Certainly by mere coincidence, Xi’s historical third-term re-election took place on the same day, March 10, when the infamous. Yuan Shikai was elected President of the Republic of China in 1912. Yuan later tried to proclaim himself Emperor, betraying the Republican ideals, and is generally vilified by Chinese historians.

After Xi Jinping’s re-election, censors noted an uncommon proliferation of posts simply reading “二次元”, usually indicating the “two-dimensional space” of anime, comics, and games (ACG), which are connected and part of the same youth subculture. If you believe there was nothing wrong about it, you are not smart enough to join the ranks of the CCP censors. They understood that for a linguistic phenomenon that is rare but not unique, “二次元” can also be read as “the second coming of Yuan Shikai.” By the way, censors were right. Some netizens really played with the two meanings of “二次元” to quietly criticize Xi’s re-election.

Others posted links to an old essay on Yuan Shikai’s passion for steamed buns. Again, this was not difficult to understand for the average Chinese, who knows that Xi Jinping is fond of steamed buns too. Actually, Xi made a steamed bun restaurant chain called Qingfeng famous in 2013 when he went there to enjoy his favorite dish. However, calling him “Xi Baozi” (Steamed Bun Xi) was later also forbidden, after some netizens compared his face to a steamed bun, which was deemed even more irreverent than comparing him to Winnie the Pooh.

Finally, censors and their machines became so confused that for several hours last week searches for “Xi Jinping” himself were blocked in China.

While all this may seem hilarious, it also deserves a more serious comment. It shows two features that tells us a lot about contemporary China. First, fueled by fear, censorship is all-expanding. Second, Chinese should adopt desperate and oblique ways to express criticism. But they succeed. Their humor is an expression of freedom, and is stronger that the censors’ stupidity.