Zhou is a well-known activist for human rights in China. He survived the Tiananmen Square massacre and harbors no illusions: today, the situation is worse than ever.

by Marco Respinti

“Violence and fear are the weapons of the Chinese Communist government.” Zhou Fengsuo punctuates the syllables in slow, terse English and gets right to the point. He speaks without hesitation. His eyes are filled with memories. Tiananmen Square, the night between June 3‒4, 1989. Tanks crushed the students who for days had been calling for freedom. They did not expect that denouement, Zhou among them. A student in Beijing’s Qinghua University, he was one of the leaders of the protest. Today he is 56. Born in Xi’an, the capital of the northwestern province of Shaanxi, he lived through it all and saw it all. I ask him: “How many died in that massacre?” He replies: “It is impossible to know. The survivors were swallowed up by prisons. Their families grew old and died. The regime concealed or destroyed evidence.” He is right. Western sources, however, suggest the shocking figure of up to 10,000 casualties. “The government sent elite troops against us,” Zhou says.

How did you make it out alive?

We had climbed to the Monument to the People’s Heroes. Bullets pelt down, tanks advanced but with difficulty. Several students were in fact throwing themselves in the middle to block their path. They were protecting us. Nobel Peace Laureate Liu Xiaobo (1955–2017) negotiated an escape route. But we were divided. I was among those who wanted to stay. Soldiers came to pull us down. I still keep a bloody flag with which we wrapped one of the fallen. In the confusion some fell; others, including me, managed to save themselves.

What happened after?

I became public enemy no. 5. I spent a year in the Qincheng village prison, northwest of Beijing. For the first three months, I had handcuffs on my wrists all the time. I was starving—food was scarce and deliberately bad. We never went out. I saw the sky for less than ten days in twelve months. I was always sick, and they continuously interrogated me with harsh methods, trying to bend me. But I survived for the second time. I was released under public pressure only to be sent to an ideological re-education facility in Yangyuan County, in northern Hebei Province. A solitary confinement, in a remote location. I survived again. Finally free, I studied Engineering. When I was invited to study Physics in the United States of America, I was denied a passport. For five years. In the end, I got it in 1994; in January, I left. I became a US citizen in 2002 and the following year, in California, I was baptized in the Tree of Life Church as a Protestant Christian from the agnostic I was.

You coordinate two organizations in the US…

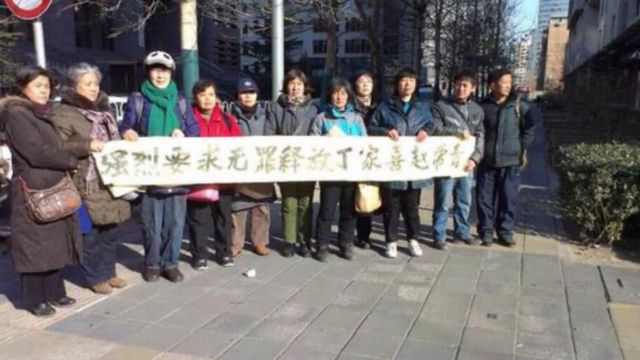

I am the executive director of the New York-based “Human Rights in China.” This was created in March 1989, before Tiananmen, by some Chinese students living in America, who wanted to do more for prisoners of conscience in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). In 2004, I also co-founded “Humanitarian China” to financially support political prisoners and their families in China. We assist a hundred of them every year, more than a thousand all together. The regime aims at scaring, isolating them: we give them a sense of belonging.

Is the organization able to provide also legal assistance to them?

To some of them, but it is increasingly difficult to find available lawyers. The famous “709 Crackdown,” or the repression which targeted and hit lawyers starting on July 9, 2015, has changed the scenario.

How is the situation in China today?

Very bad. We thought it was bad a year ago, but twelve months later it is worse. President Xi Jinping’s management of power is a crescendo that seems unstoppable. Taking advantage of anti-COVID measures and digital technology, he now virtually controls all citizens, who are divided and surveilled. It is a total grab. One can be arrested for an “unauthorized” dinner, as it happened in December 2019 to human rights lawyers Xu Zhiyong and Ding Jiaxi, who were sentenced to 14 and 12 years in prison, respectively. And that was the second time it happened to them. There are also Communist student groups defending workers’ rights that the Communist government persecutes as troublemakers. Today, the PRC presides over a totalitarian regime endowed with so vast and pervasive power as it has never been seen in all human history.

But is President Xi a particular harsh Communist or is the Communist system intrinsically evil?

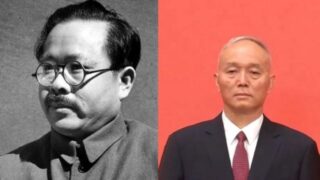

Xi is not a surprise at all. Some believed him to be a reformer—it happened even among dissidents—since his father was purged, but Xi is a legitimate son of Mao Zedong, the great butcher (1893–1976). It is not just him, however: all the post-Maoist communist leaders are the same, including Deng Xiaoping (1904–1997), who is often painted as an innovator. He granted certain measures of economic freedom, but he was another butcher. He began by fighting corruption in 1983, in the name of which he imprisoned and killed. Then Tiananmen happened—and then post-Tiananmen, when he uttered the historic words “We would kill 200,000 people in exchange for twenty years of stability.” The key is always “security”: of the state—and it costs corpse after corpse of those who routinely demand only freedom. That is the nature of a Communist regime: it never changes. Mao, Deng, Hu Jintao, Jiang Zemin (1926–2022), Xi: they are all the same. Maybe the rhetoric varies a bit, but that only lures foreigners. On occasions, the West chooses to lie to itself by believing the regime’s lies. Communism, on the other hand, never changes. Xi is a natural product of an evil system.

You have spent all your life fighting for freedom. What made you do it?

It is my duty. I owe it to my country, which I love.

Note: An Italian version of this interview was published by “Libero quotidiano” on March 31, 2024.