It is unclear when the artist first met the Theosophical Society. General Carlo Ballatore and politician Giovanni Amendola played essential roles.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 4 of 5 (published on consecutive Saturdays). Read article 1, article 2, and article 3.

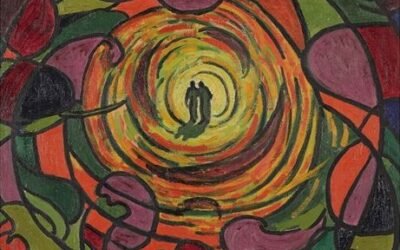

When did Balla first encounter Theosophy? In 1984, the artist’s daughter Elica stated, “Balla was interested in psychical phenomena and attended meetings of a Theosophical Society led by General Ballatore, where Spiritualist séances were also held.” She further explained the Theosophical significance of Balla’s painting “Trasformazione forme spiriti” (Spirit–Form Transformation), one of at least three works created between 1916 and 1920 exploring themes of reincarnation and the movement of human souls.

There is little doubt that this was a period of intensive engagement with Theosophy for Balla. Italian musicologist Luciano Chessa observed in paintings from the 1910s, beginning with “Iniezione di futurismo” (The Injection of Futurism) and including the patriotic paintings of 1915 advocating for Italy’s intervention in the First World War, that “the two ‘L’ and the ‘A’ of Balla’s name [in the signature] intertwine to form a swastika, in which the hooks are oriented toward the right.” This constitutes a noteworthy discovery, given that the swastika was a fundamental symbol of the Independent Theosophical League. The “Theosophical Society presided by General [Carlo] Ballatore [1839–1920]” referenced by Balla’s daughter was active within the Independent League.

On the other hand, Elica’s late reminiscences provide no evidence that Balla became acquainted with the Theosophical Society only as late as 1916. Even Chessa’s hypothetical date of 1914 for Balla’s first Theosophical contacts is probably too late. As early as 1902, Balla was described as keeping “contact daily” with Randone, and Randone was at that time an active member of the Theosophical Society. It isn’t easy to imagine that Randone never mentioned Theosophy to Balla.

The exact time when Balla first met liberal politician Giovanni Amendola (1882–1926) and his Lithuanian wife Eva Kühn (Eva Oskarovna Kiun, 1880–1961) remains unclear. Although Balla later adopted a pro-Fascist stance and Amendola became a critic and martyr of the Fascist regime—dying in 1926 after being beaten by Fascist militias—their friendship was strong during Giovanni’s son Giorgio Amendola’s (1907–1980) childhood. Giorgio, who would become a leader of the Italian Communist Party, recalled that around 1915–1916, when he was five or six, Balla frequently visited his parents’ home in Rome and admired Giorgio’s drawings, jokingly calling him “a Futurist painter.” These are Giorgio’s earliest memories, but his parents’ friendship with Balla likely predates that. The Amendolas moved permanently to Rome in 1912. However, they had spent considerable time in the city earlier. Additionally, Amendola and Randone joined the same Masonic Lodge in Rome in 1905, and Eva Kühn reportedly attended Randone’s Spiritualist séances.

In 1900, Giovanni Amendola, at only 18 years old, joined the Theosophical Society of Rome. His high dedication led to him being appointed secretary at a meeting chaired by Leadbeater in 1902, contributing to the founding of the Italian Theosophical Society. In 1903, he met Eva Kühn, a young Lithuanian intellectual who attended the society’s meetings in Rome, though many of its teachings disturbed her. They fell in love, but Amendola explained he had chosen to live in chastity—something not uncommon in Theosophical circles at the time. This decision made Eva uneasy, but she accepted it and even defended it against Besant, who, during a public lecture in Rome in October 1904, argued that some urges and temptations cannot be overcome. According to Besant, the only way to live peacefully was to surrender to them quietly.

Besant felt insulted by Eva’s comments, leading to a tense confrontation. Eva recalls that Besant, “with her white hair, dressed entirely in white, looked at me with a harsh, menacing stare that made me feel as though I had been struck by lightning.” It was a severe incident: Eva struggled to recover and spent several months in a psychiatric hospital undergoing intensive treatments. While many Italian libertarian and feminist women joined early Theosophical circles, they often felt uneasy due to Besant’s and Cooper Oakley’s authoritarian manner.

This incident may have contributed to Amendola’s decision to leave the Theosophical Society in 1905, where he described it as “evil” and expressed his desire for its “most complete ruin.” He remained in contact with friends leaning towards Steiner and subsequently Anthroposophy for some time, but he eventually fully distanced himself from Theosophical beliefs and married Eva in 1907.

Amendola joined the Grand Orient of Italian Freemasonry in 1905 and became a political ally of Nathan, a close friend of Balla during the same period. He was a member of the Socialist Party from 1905 to 1907, when Balla collaborated with the socialist publication “L’Avanti.” Whether Amendola befriended Balla while still a Theosophist or shortly thereafter is probably not crucial. Theosophy played a significant role in the Amendolas’ lives, and it was likely featured in their conversations with the artist. Despite Eva’s negative experience, Balla continued attending General Ballatore’s Theosophical meetings. However, this experience might have influenced his preference for the meetings of the Independent Theosophical Group over those of the Italian Theosophical Society, which was loyal to Besant.

One of Balla’s most renowned works is “Lampada ad arco” (Arc Lamp), which is housed at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The exact date of its creation is debated. In the 1950s, the elderly Balla claimed it was painted in 1909 and inspired Marinetti’s 1909 poem “Uccidiamo il chiaro di luna” (Let’s Kill Off the Moonlight), rather than the other way around. Most scholars agree that Balla was inspired by Marinetti and created “Lampada ad arco” after he signed (but did not co–author) the 1910 second edition of the “Manifesto dei pittori futuristi” (Manifesto of the Futurist Painters). The “1909” date on the top left refers to the start of Futurism, but the work was completed in 1911. Balla signed the 1910 Manifesto to support his pupil Boccioni, while the leading Futurist group was based in Milan, and he was in Rome. After attending Boccioni’s “esoteric” Futurism lecture in Rome (29 May 1911) and meeting Marinetti, Balla collaborated with the Futurists. In 1912, he offered “Lampada ad arco” to Boccioni for the Futurist exhibition at the Bernheim-Jeune Gallery in Paris. Although Boccioni initially accepted and listed it in the catalogue, he later rejected it, considering that the “lampada” still reflected the Divisionist style, which the younger Futurist artists, influenced by Cubism, aimed to move beyond.

The painting acts as a transitional piece, showing electric light (symbolizing modernity) defeating moonlight (representing romanticism). This Futurist idea is set against early twentieth-century Masonic traditions. The central star, implicitly Masonic, represents the Kingdom of Italy and the Third Rome, overtaking the Catholic obscurantism of the Second Rome. The long-standing alliance between religion and feudal forces was about to end.

Nathan, the Mayor of Rome, was troubled by internal conflicts within his coalition after Balla painted his portrait in 1910. He resigned in 1913 but remained an influential Masonic figure as Grand Master of the Grand Orient of Italy from 1917 to 1919.

Balla accepted the Futurists’ rejection of his “Lampada ad arco” and delved deeper into Futurism’s new visual styles. He focused on how movement is perceived and represented, building on his early collaborations with photographers in Turin. His interest in “photodynamicism” grew, a technique devised by brothers Anton Giulio (1890–1960) and Arturo Bragaglia (1893–1962) to capture motion in photographs. The Bragaglias aimed to depict time and movement and believed photography could uncover invisible and mystical aspects of reality, like auras. Inspired by spirit photographs from séances, they tried documenting spirit manifestations and ectoplasm. Balla met the Bragaglias in 1912, and their mutual influence is evident in the following years.

Balla’s “Dinamismo di un cane al guinzaglio” (Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash, 1912), now in the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York, was the subject of a photodynamic image by A.G. Bragaglia. It showcases Balla’s early yet characteristic chrono-photographic experiments. In 1912, he traveled twice to Düsseldorf to work on designs for Arthur and Grethel Löwenstein, from a family of a female pupil in Rome. It’s unclear whether he met the Dutch architect Johannes Lauweriks (1864–1932) there, as Italian scholar Giovanni Lista suggests.

Lauweriks, an active member of the Theosophical Society, had left his position at the Düsseldorf Kunstgewerbeschule in 1909 to lead the Staatliches Handfertigkeitsseminar in Hagen. Nonetheless, his influence was still felt in Düsseldorf.

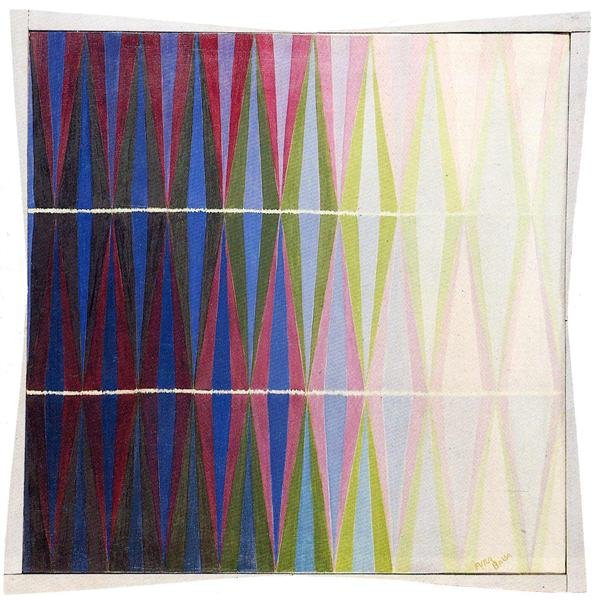

Balla explored the dynamics of light and color in Germany, inspired by “Thought-Forms” and Rudolf Steiner’s work. He began sketching what he called “compenetrazioni iridescenti” (iridescent interpenetrations), geometric compositions of light and color, although the date he adopted the term remains debated.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.