Since its origins in the late 19th century, Italy’s Theosophical Society has influenced leading artists.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 1 of 5 (published on consecutive Saturdays).

Giacomo Balla (1871–1958) was a key figure in the Italian Futurist movement and pioneered abstract art in Italy. He also maintained strong ties with the Theosophical Society and other esoteric organizations.

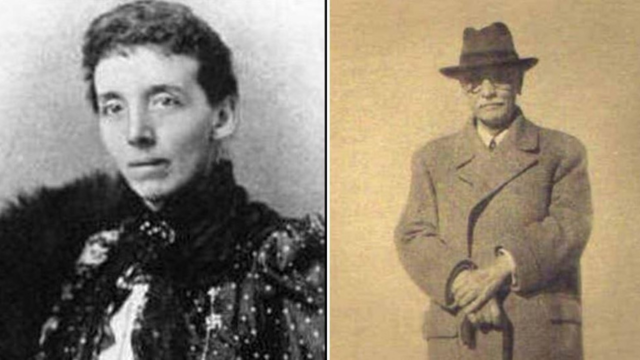

Madame Helena Blavatsky (1831–1891) and Colonel Henry Steel Olcott (1832–1907) visited Italy multiple times. In the early 1890s, British expatriates established the first Theosophical centers in Italy, and on 22 February 1897, the Rome association officially joined the Society. After Blavatsky’s death, notable international Theosophists like Olcott, Annie Besant (1847–1933), Charles Webster Leadbeater (1854–1934), and Isabel Cooper-Oakley (1854–1914) actively promoted Theosophy in Italy. The Society appointed Cooper-Oakley to lead efforts there, where she devoted significant time. Besant delivered several lectures in Rome for the newly established Rome Theosophical Association.

Theosophy’s message quickly spread through Italian cities, attracting Freemasons who, although critical of Catholicism, were dissatisfied with the Positivism prevalent in some Masonic lodges and searched for a different spiritual path. Notable Italian intellectuals, such as Maria Montessori (1870–1952), joined the Theosophical Society; she even taught courses at its headquarters in Adyar, India, in 1939. The Italian Section of the Theosophical Society was formally founded in Rome on February 1, 1902, during a convention led by Leadbeater.

Internal conflicts within the international Theosophical Society soon impacted the Italian Section. In 1905, a dissident group, including Giovanni Colazza (1877–1953), broke away from the Italian Section, and by 1911, they had founded Italy’s first Anthroposophical organization. Between 1906 and 1908, additional members left amid allegations of immorality against Leadbeater. Some dissidents continued to be active within the Theosophical Group “Rome,” which preserved links to the 1897 Rome Theosophical Association. In 1909, a faction opposing Besant and Leadbeater emerged in Benares, India, known as the Independent Theosophical League. Italian dissidents loosely aligned with the Benares group the following year and formed the Italian Independent Theosophical League, led by Decio Calvari (1863–1937).

The League gained control of “Ultra: Rivista Teosofica di Roma” (1907–1934), making it a key spiritual and literary influence in Rome for over twenty years. While discussions about Jiddu Krishnamurti (1895–1986) and Rudolf Steiner (1861–1925) were lively, there was no strict separation among the different Theosophical groups. Theosophists from the Independent League, those loyal to Adyar, and Anthroposophists often collaborated by publishing in the same journals and attending common events. The Independent Theosophical League even hosted Steiner for a lecture at its headquarters. Italian scholar of esotericism Marco Pasi notes that “participating in the activities of the Independent Theosophical League did not require affiliation or a declaration of Theosophical faith.” In 1939, the Fascist Regime dissolved the Italian Section of the Theosophical Society. After World War II, the Society was re-established and continued its activities in Italy.

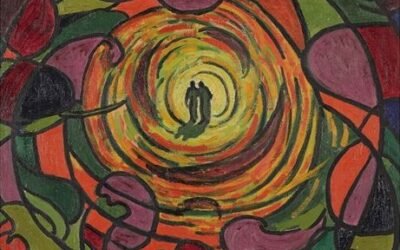

Like many other countries, Theosophy initially influenced Italy’s visual arts at the height of symbolism. Gaetano Previati (1852–1920), a prominent Italian painter who moved from Symbolism to Divisionism, a Neo-Impressionist style, was not a member of the Theosophical Society. However, he interacted with Belgian Symbolist artists who supported Theosophy, mainly through his participation in the Salons de la Rose–Croix, organized by French novelist Joséphin Péladan (1858–1918). Although Péladan was skeptical of Theosophy, he tolerated some of its advocates attending his exhibitions.

Several Italian artists influenced by Previati had direct or indirect connections to Theosophy. Giuseppe Maffei (1821–1901), who believed spirits guided him, assisted Italian Senator and Masonic leader Federico Rosazza (1813–1899) in realizing his dream of transforming a small village in the remote Cervo Valley into a unique town filled with esoteric monuments, which still bears his name, Rosazza. In Italy, it is common for such towns to feature a Catholic church. The one in Rosazza was adorned with Masonic and Theosophical symbols, which caused problems with the local Catholic bishop.

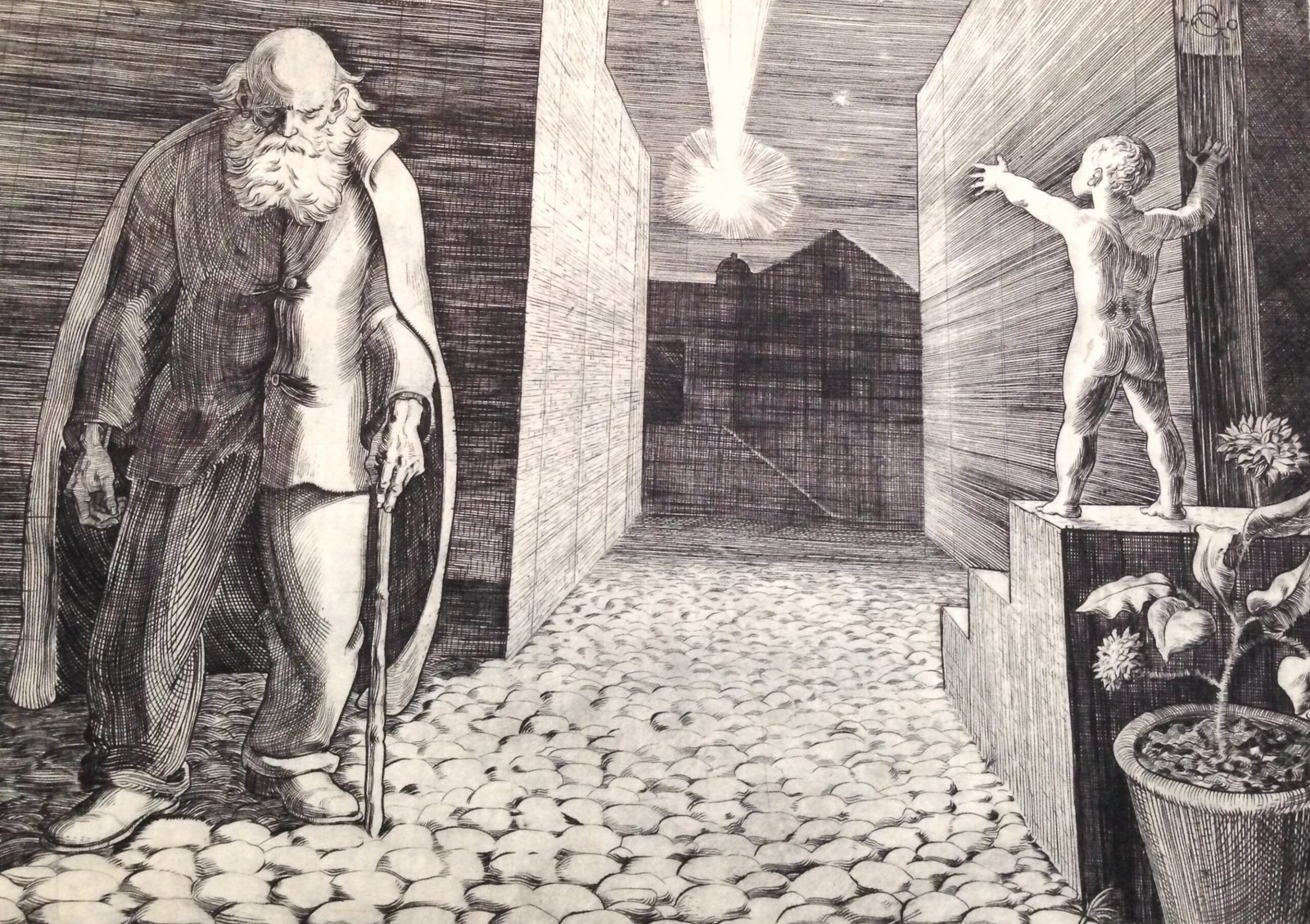

A younger disciple of Previati, Alberto Helios Gagliardo (1893–1987), became a prominent engraver and was actively involved in the Genoa lodge of the Theosophical Society.

Two Symbolist artists engaged with early Italian Theosophists: Raoul Dal Molin Ferenzona (1879–1946) and Charles Doudelet (1861–1938), a Belgian engraver who moved to Livorno in 1908; their primary esoteric focus was, however, Rosicrucianism.

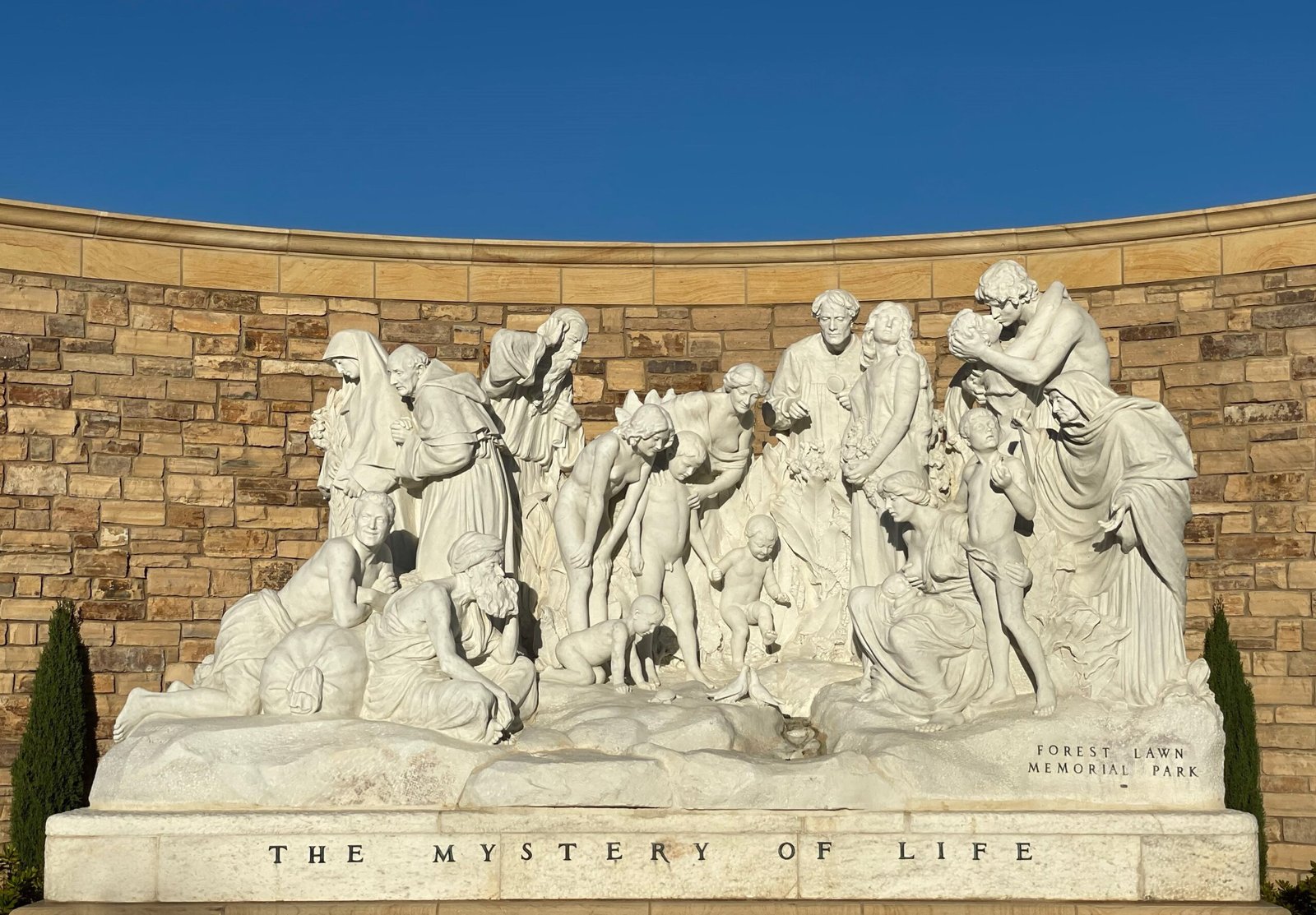

Ernesto Gazzeri (1866–1965), a sculptor from Modena, was influenced by Theosophy when creating his large sculpture “Il mistero della vita” (The Mystery of Life, 1918). The statue depicts eighteen figures around a mysterious source symbolizing life’s origin and is now located in Forest Lawn Memorial Cemetery in Glendale, California.

Although Futurists openly rejected Symbolism, they highly regarded Previati mainly for his esoteric links rather than his artistic style. While they admired modernity and scientific progress, they also viewed the exploration of occult and hidden forces as a vital part of modern science—what they believed to be the science of the future. Irma Valeria, the pseudonym of Irma Zorzi (1897–1988), stated that “we [Futurists] are without doubt occultists.”

In the late 1960s, art historians and critics like Maurizio Calvesi (1927–2020), Mario Verdone (1917–2009), Germano Celant (1940–2020), and Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco (1939–2002) revisited the connection between Futurism and esotericism. Literary historian Simona Cigliana thoroughly examined this topic in her 2002 book “Futurismo esoterico” (Esoteric Futurism). Additionally, musicologist Luciano Chessa explored it in the first part of his 2012 monograph on the Futurist composer and painter Luigi Russolo (1885–1947). Moreover, scholars such as Giovanni Lista, Flavia Matitti, Fabio Benzi, Elena Gigli, and Mario Finazzi have investigated Balla’s esoteric and Theosophical ties.

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876–1944), the founder of Futurism, was acquainted with Spiritualist mediums and Rosicrucian intellectuals like Paul Adam (1862–1920). Early in his career, while traveling between Paris and Milan, he was part of a circle that included journalist Jules Bois (1868–1943), known for his writings on the occult subculture, and the popular esoteric author Édouard Schuré (1841–1929), who wrote “Les Grands Initiés: Esquisse de l’histoire secrète des religions” (The Great Initiates: A Study of the Secret History of Religions, 1889), and the painter Paul Ranson (1861–1909).

All were members of the Theosophical Society. Ranson collaborated with Marinetti when he designed costumes for the performances of “Roi Bombance” (King Guzzle, 1905) at the Théâtre Marigny (directed by Lugné-Poë [1869–1940], April 3–5, 1909). Schuré was at a salon hosted by Madame Berthe Périer (1857–1942), where Marinetti recited from the text in 1905. He publicly embraced Marinetti and called the drama “an immortal work.” Ranson also introduced Marinetti to his most talented art student, Polish–born painter Tamara de Lempicka (1898–1980), who was involved in several occult and Theosophical groups, including those around Natalie Clifford Barney (1867–1972). Lempicka captivated Marinetti with her “bad girl” poses. The two plotted to set fire to the Louvre, but thankfully, nothing came of it.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.