Cities and villages across Shanxi are implementing special measures as part of the nation-wide “struggle to clean up gang crime and eliminate evil.” Promoted as a campaign against organized crime, it is yet one more of President Xi’s initiatives targeting religious groups and churches in China.

Initiated in January this year, the campaign to “clean up gangs” has been actively implemented in provinces across China. In the first month since its inception, over 10,000 people have been arrested. Authorities claim that the anti-gang drive is intended to “strengthen political power at the grassroots level,” with wide-scale mandate delegated to law enforcement and local governments.

Linfen city’s United Front Work Department (UFWD) in northern Shanxi Province held an emergency meeting on September 12, attended by local representatives of the five authorized religions. The participants were informed that starting from October, all of the city’s counties, townships, and villages must establish a specially-designated institution for the campaign to “clean up gang crime and eliminate evil” and designate an information officer to monitor “non-official” religious venues and their congregations. All religious groups on the list of xie jiao (heterodox teachings) and meeting places for churches not approved by the government were designated as the principal targets of this campaign. The authorities also demanded to crack down on the South Korean religious missions in the province.

On September 18, the Communist Party committee in one of the villages in Linfen gathered all its members for a meeting where the village party secretary reiterated the message that the campaign to “clean up gang crime and eliminate evil” was mainly aimed at arresting people of faith. The three-year campaign has specific goals to be achieved each year: 2018 is dedicated to treat the “symptoms;” 2019 – to deal with the “underlying causes;” and in 2020, the “root” of the issue should be resolved. Every party member was required to write a statement of guarantee, pledging that no one in their family believed in God. Two young men were hired to monitor the movement of non-residents of the village, and party cadres were ordered to take photos of anyone who is suspected of having a religious belief and report about such cases to the village committee.

A village committee in the area of Yuncheng city issued an Open Letter on Cleaning Up Gang Crime and Eliminating Evil to villagers and demanded them to sign an “anti-xie jiao commitment card.”

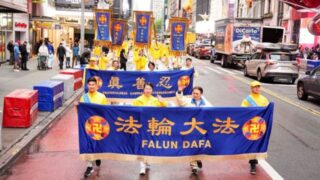

The campaign also involves businesses and state institutions. Hospitals and clinics in every town of Linfen city were issued quotas: at least one person who believes in God should be reported every week. Believers in Islam, Almighty God, and Falun Gong were indicated as targets that must be “swept away.”

The principal of a school in Yuncheng city told all teachers that the government was demanding all “dark and evil forces,” including believers, to be purged within three years. Teachers and students are forbidden from believing in God; if anyone discovers that a friend or a relative is a believer, they should report them to authorities immediately. According to the school’s students, teachers wrote “clean up gang crime and eliminate evil” on blackboards in each classroom and asked students whether anyone in their family was a believer.

The authorities have set up a variety of reporting methods for the implementation of the campaign, including text messages, WeChat groups, and written reports.

Rights activists fear that the current anti-gang campaign will turn into one more ideological and political repression by the Chinese authorities, like the infamous trials in the southwestern city of Chongqing in 2009 or China’s first major national crackdown on crime launched in 1983.

Deng Xiaoping, the mastermind behind the 80s campaign, implemented it in the best traditions of the Cultural Revolution: public trials and executions, even for small misdemeanors. To cater to the party’s policies, local governments competed in the number of arrests, putting sometimes innocent people to death by fraudulently claiming achievements in the fight against crime.

Described as “China’s trial of the 21st century,” the crackdown on alleged organized gangs in Chongqing was later criticized for being a tool to do away with political rivals of the city’s party chief Bo Xilai and a multitude of reported cases of torture.

Reported by Feng Gang