Examining the statements of a leader from a marginalized and actively persecuted new religious movement on the authority to declare a holy war.

by Márk Nemes

Article 1 of 2

“Bitter Winter” has already published two separate series of articles—a general introduction by Massimo Introvigne and Karolina Maria Kotkowska, as well as a more in-depth analysis of the movement’s social reception by Susan J. Palmer— as well as several individual reports written by Introvigne and Rosita Šorytė on the persecution of the Ahmadi Religion of Peace and Light (AROPL). These articles trace back the apparent ill intent toward this new religious community to a variety of reasons, including simple misunderstandings and misreadings based on cultural differences, unfounded fears of Islamic radicalism, overinflated and out-of-context statements by popular media, and even targeted attacks from authors without proper academic training, including a particular “anti-cult hero of the digital age.”

Besides the already present scholarly (etic, not to be confused with ethic) comparative analysis, the most recent of which was just published by Benjamin Zeller, AROPL has its own means and methods of communicating its beliefs and worldview in a structured manner—of course, from an etic standpoint, providing rich research material for scholars such as ourselves.

Their largest YouTube channel (out of nine channels the movement currently manages), “The Mahdi Has Appeared,” has around 84,000 subscribers and more than 4,100 videos. This site is where Abdullah Hashem Aba Al-Sadiq—or as the members refer to him from their emic point of view, the Mahdi—shares his teachings and declarations on various subjects.

On June 16th, 2025, a new video was uploaded to this site as part of the “The School of Divine Mysteries” series. It was later followed by another explanatory video, published on another AROPL channel, entitled “The Ahmadi Religion of Peace and Light | AROPL.” Contrary to previous entries on the former playlist, most of which focused more on the “esoteric” subjects of AROPL’s alternative worldview—such as collective consciousness and the course of human evolution, the existence of so-called “supersouls,” the theory of the multiverse or the alternative histories and futures of the world—this episode covered a highly controversial and regularly misunderstood and misused subject in Islam: jihad and the rights to declare and lead a religious holy war. The episode discussed the conditions and verifications of a militant holy war in Islam. It concluded that the Mahdi, in AROPL’s understanding, Abdullah Hashem, has the sole right to announce and lead one such conflict.

However, this statement carries several nuances, as in AROPL’s understanding, the notion is situated within the broader spiritual framework of the “greater jihad,” referring to the internal struggle for faith and righteousness rather than a call for physical warfare. Still, there is no need to underline how such a subject can—and possibly will, in due time—be criticized by both mainline Islamic religious authorities and anti-cult activists, who do not always make efforts to understand specific previously known terms in new religious environments. The negative connotations of jihad—especially in its offensive interpretation, which on its own carries several oxymoronic elements in the contexts of kalam, or Islamic speculative theology—may open a new front of hostility against this already persecuted minority religious community. This article aims to provide an external, in-depth scholarly overview of Hashem’s statements and understanding of jihad, contextualizing his words in the postmodern, prophetic-monotheistic, esoteric-conspiritual worldview of AROPL.

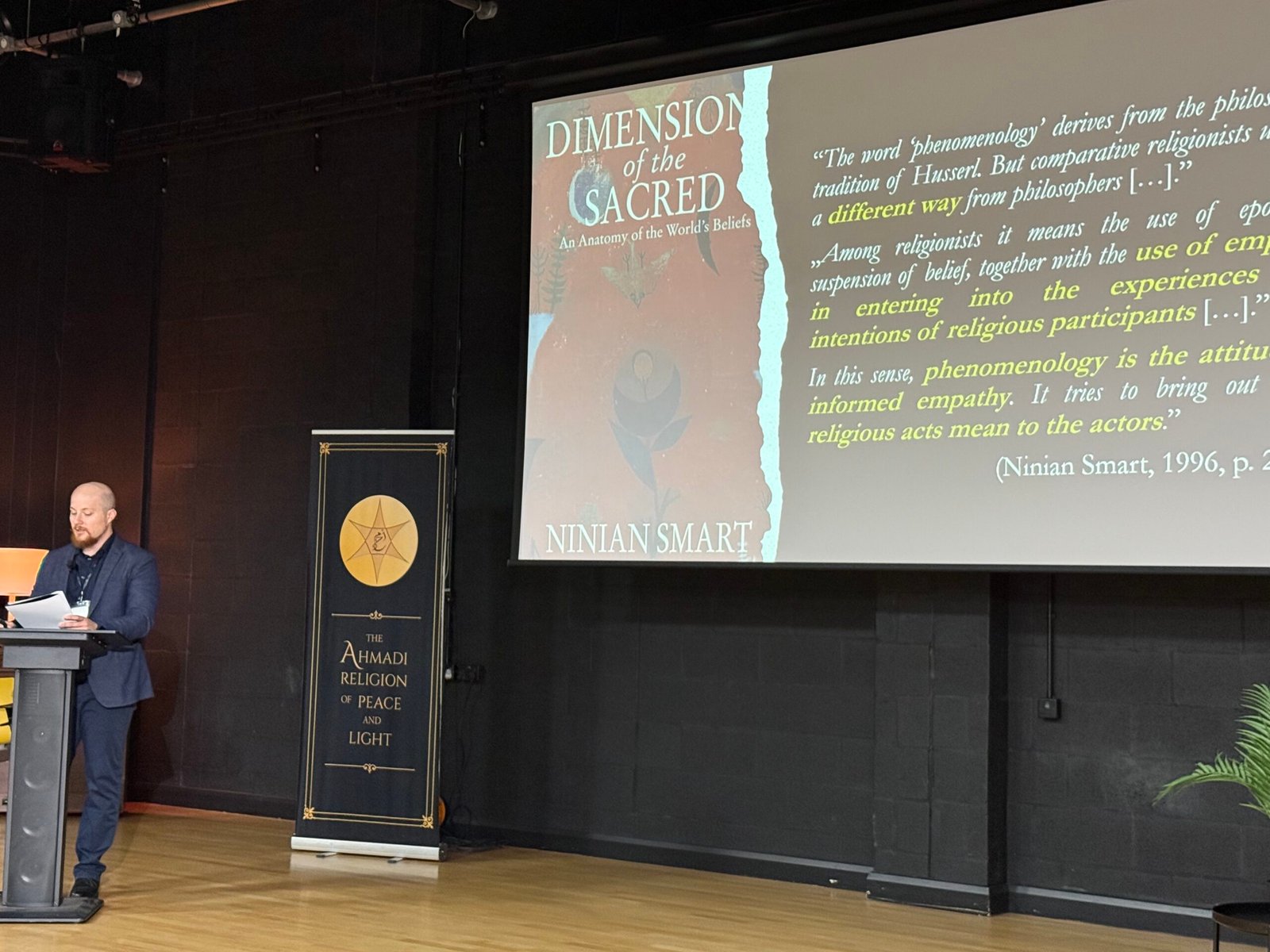

It is necessary to note that, as scholars, it is not our duty to evaluate which statements of Hashem are true or false, and in which contexts, jihad could be justifiable. In the author’s personal empathetic view—as a European who was born into and raised under the cultural shield of contemporary Christianity—no situation would legitimize or justify declaring holy war on others. As researchers of religions, however, our evaluation is not determined by a self-reflective cultural view, but by methodological agnosticism.

This is even more true when we discuss new and emergent religions, which are, in general terms, culturally, morally, socially, dogmatically, ritually, materially, and maybe even experientially different from ours. As scholars of religions, we do not evaluate theological declarations—we leave these to clergy, theologians, and to some extent religious practitioners—but analyze the empirically detectable effects of these statements in the surrounding contemporary world. We aim to objectively describe, contextually analyze, and analytically provide the most accurate scholarly interpretation of an examined phenomenon.

While exercising our scholarship, we also stand firmly for freedom of expression and the practice of religion or belief. As such, we believe that members and representatives of AROPL, either as a movement or as individuals, are entitled to practice and share their beliefs with possible sympathizers, just like every other, more or less established religion does—even if some of their statements may feel uncomfortable, confusing, or unacceptable for a particular listenership.

Jihad may be one of the most contested terms in Islam. The term can be translated as either striving or struggling in the path of God. Generally, it refers to striving for correct practice, the struggle for interpretive clarity while reading the Quran and Hadith (also known as Greater Jihad), and the religiously sanctioned holy warfare declared by caliphs (Lesser Jihad). In the non-Muslim world, this latter meaning could be the most prevalent—and dreaded—understanding.

Like the term’s complex meanings, its history is just as convoluted. In a historical perspective, jihad doctrines of warfare were formulated in the wake of the early conquests of the 7th–8th century. However, the interpretation of the Greater Jihad precedes this (early 7th century). The emergence of the Arabic and Ottoman Empires reformulated the meaning of the original term. Later, by the 18th and 19th centuries—coinciding with the onset of the second millennium of the Islamic calendar—novel movements appeared in Muslim societies, reviving jihad differently.

Most of these movements were Mahdist, following self-proclaimed prophets, like the one led by the Sudanese Mahdi Muhammad Ahmad (1843–1885). After World War II, the term jihad reappeared in Muslim public discourse. This time, the meaning and target shifted accordingly: besides the new neighboring nation of Israel, pro-Western Muslim “un-Islamic” labeled politicians also became targets of religious attacks.

It is not necessary to further detail the subsequent decades: Afghanistan’s Soviet occupation (1979–1989) brought about anti-Soviet and reignited anti-Western sentiments. The most infamous of this era was led by Osama bin Laden (1957–2011) and Ayman al-Zawahiri (1951–2022) and grew to become al-Qa’ida (The Base). After September 11, 2001, most of the Muslim world strived to erase the term jihad from their vocabulary in any meaning whatsoever, as an effort to distance themselves from the rise of Muslim terrorism.

Nevertheless, one cannot omit or erase key elements of a religion. Reclaiming and reinstating this term’s original, atemporal cultural meaning – the inner struggle of the Greater Jihad–could be a much more successful effort. Professor Caleb Heart Iyer Elfenbein, scholar of Islamic studies, brings one example: a Muslim movement that labeled itself as engaging in jihad pursued nonpolitical and nonviolent goals. The Tablighi Jamaat, originating from early 20th-century India, is an example that grew to be a global movement. In their understanding, jihad refers to the struggle to keep Muslims aligned with Islamic values, rather than Western modernity and secular influences. They practice jihad as striving for correct practice, emphasizing personal piety and proselytizing–as the Greater Jihad. Similar examples can be seen within the Sufi orders. Since the 12th century, Sufis have defined jihad from a spiritual point of view, referring to an individual’s inner struggle against unbelief and sin or to society’s struggle to bring the Islamic community in line with God’s laws.

Márk Nemes is a historian and a graduate in the academic study of religions. He received his doctorate in philosophy at the University of Szeged’s PhD program in 2025 and works as a researcher at the Hungarian Academy of Arts’ Research Institute of Art Theory and Methodology. As an awardee of the Hungarian National Eötvös Scholarship, he served as a visiting researcher at CESNUR from 2023 to 2024. For the past 10 years, he has focused on researching new, alternative, and emergent forms of religiosity in Hungary, Iceland, the US and most recently, in Italy. Since 2025, he serves as the Deputy Director of CESNUR