A France 5 “documentary” offered a textbook example of how “not” to present minority religions to the public.

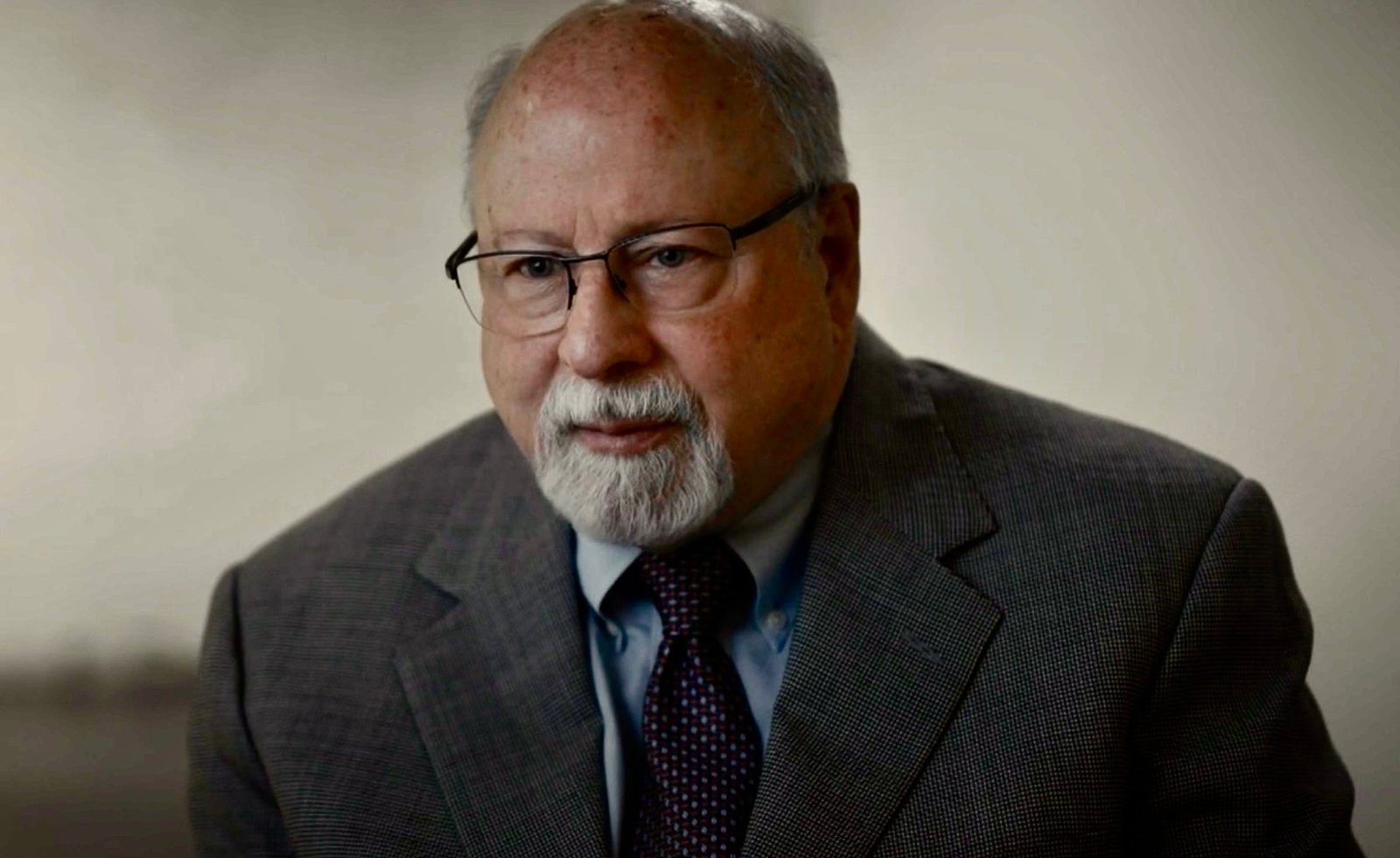

by Massimo Introvigne

France 5’s latest documentary on Scientology, which aired on Sunday, February 15, cannot be reviewed as a journalistic investigation. It was something different and similar to a baroque autodafé burning the heretics in the public square: a ritual performance—one of those familiar televised ceremonies in which the public broadcaster reenacts its own certainty. The heretic is always the same, the tone unwavering, the conclusion predetermined. One begins to suspect that the only suspense left is whether the production budget will be higher than that of the last similar documentary.

This time, the channel, a public broadcaster funded by French taxpayers, entrusted the project to Tohubohu, a production company whose name evokes disorder but whose financial relationship with France Télévisions appears remarkably stable. The director, Romain Icard, is not only the creative mind behind the documentary but also a co-founder of Tohubohu. His business partner, Thierry Demaizière, is married to a member of France Télévisions’ Ethics Committee. It is a charmingly circular arrangement: the producer’s spouse helps oversee the ethics of the broadcaster that commissions the producer. One could call it synergy. Others would call it a conflict of interest. French broadcasting regulations certainly lean toward the latter. But perhaps the Ethics Committee, like the moon, exerts its influence in ways invisible to the naked eye.

The documentary opens with the solemnity of a public service announcement. Scientology, we are told, is dangerous, opaque, and manipulative. These are claims that deserve examination. But examination requires method, and method requires sources. France 5’s approach to sourcing resembles a casting call for a play whose script has already been written. The production presents a handful of “rare” and “precious” witnesses.

Yet these witnesses are anything but rare. They are the same professional ex-members and anti-cultists who appear in documentary after documentary, interview after interview, often compensated for their participation. Their testimonies are not new; they are repackaged. The documentary treats them as if they had been discovered in a remote Himalayan monastery, when in fact they are as ubiquitous in anti-Scientology media as weather forecasters are on the evening news.

Take Tony Ortega, introduced as a journalist who has spent thirty years investigating Scientology. That is one way to frame his career. Another would be to mention his vicious anti-cult diatribes and his abrupt departure from a major American publication after his fervent defense of Backpage.com, a website later shut down by the FBI for facilitating child trafficking. His record includes not only controversial editorial choices but also documented instances of fabricated or embellished reporting, criticized by the “Columbia Journalism Review.” None of this appears in the documentary. Perhaps it was deemed irrelevant. Or perhaps it was simply inconvenient.

Then there are Marc and Claire Headley, whose personal history with Scientology is complicated but whose legal history is quite clear. Their multimillion-dollar lawsuit against the Church was dismissed as unfounded, and they were ordered to pay $42,000 in costs. Marc Headley has acknowledged being paid for tabloid “testimonies,” sometimes up to $10,000 per story. Whether his appearance in this documentary was an act of altruism or a professional engagement is left unexplored. France 5 does not inquire; it simply presents.

The next witness appears under the pseudonym “Lucas le Gall,” though his real identity—Eric Gonnet—is hardly a secret. He is the son of a long-time anti-Scientology activist expelled from the Church decades ago and convicted multiple times in France. Gonnet claims to have spent four years in Scientology’s Sea Organization, to have held high-ranking international responsibilities, and to have been the right-hand man of the Church’s leader in California. These claims collapse under the weight of basic chronology: he spent only three months in the organization, in Copenhagen, in 1980, in a modest administrative role. He never held any significant position, never went to California, and never met the Church leader. His own writings include candid reflections on his tendency to fabricate stories. This, too, is omitted from the broadcast.

And then, in a moment of unintended surrealism, the documentary introduces a witness generated by artificial intelligence, which it claims was based on a real person, but one who was scared. France is home to thousands of Scientologists, yet the production apparently found it easier to synthesize a human being than to interview one. It is a bold editorial choice, though perhaps not one that enhances the enterprise’s credibility. Perhaps the next France 5 documentary will feature a hologram.

The parade of questionable witnesses continues. Joy Villa, presented as a “young destitute American actress,” is in fact a minor performer with a handful of background roles, now reinvented as an evangelical Christian who claims divine revelation about Scientology’s malevolence. Her personal history, including a dramatic marital dispute involving a substantial sum of money, is left unmentioned. The documentary prefers its characters to be simple, unburdened by nuance.

All of this might still have been salvageable had the subsequent “debate” offered a semblance of pluralism. Instead, the panel consisted exclusively of long-time critics of Scientology, including organizations and individuals with a history of litigation against the movement—litigation that has not always ended in their favor. UNADFI, represented by lawyer Olivier Morice, was ordered by the Paris Court of Appeal in 2015 to pay €21,000 to Scientologists for abusive legal action, a decision upheld in 2017. This context, too, was absent.

When the Church requested that a representative be allowed to participate in the debate, France Télévisions declined, invoking “editorial freedom.” The phrase is becoming a kind of talisman, used to ward off the specter of pluralism. A public broadcaster should have welcomed the opportunity for direct exchange. Instead, it chose the comfort of unanimity. The broadcaster’s response to concerns about impartiality was equally revealing. When confronted with the possibility that its obligations had been violated, France Télévisions suggested that responsibility lay with Tohubohu, the delegated producer, which had contractually agreed to shield the broadcaster from legal consequences. It is a curious defense: the public broadcaster claims editorial freedom when selecting voices, but contractual helplessness when those choices are questioned.

One does not need to be sympathetic to Scientology to find this troubling. One does not need to endorse its beliefs, practices, or organizational structure. One needs to believe that public broadcasting should adhere to the principles that justify its existence: impartiality, honesty, and pluralism. These are not decorative ideals. They are legal obligations, funded by taxpayers, intended to ensure that public media serves the public—not a narrative.

France 5 had the opportunity to include scholars of new religious movements who study them with academic rigor. France has such scholars. Bernadette RigalCellard, for example, has spent decades examining minority religions with methodological seriousness. Internationally, Donald Westbrook has published extensively on Scientology with Oxford University Press and Cambridge University Press—hardly fringe outlets. These voices were not invited. Their absence is not an oversight; it is a choice. Instead, the program relied on Stephen Kent, a Canadian sociologist whose hostility toward religions, old and new, is so pronounced that he has publicly suggested that many founders of major world religions—including the Prophet Muhammad and the Apostle Paul—suffered from severe mental disorders. He recently wrote, “Perhaps God exists, but if He (or She or It or They) do, then one wonders why God chose so many revelations to come through disordered minds.” When someone applies this psychiatric reductionism to the entire history of religion, it becomes difficult to take his sudden clinical certainty seriously when he turns his attention to Scientology.

The documentary’s defenders will argue that including Scientologists or neutral scholars would have “legitimized” the movement. This argument misunderstands journalism. Journalism is not about protecting viewers from complexity. It is about presenting complexity and trusting viewers to navigate it. A documentary that excludes all dissenting voices is not an investigation.

What France 5 offered last night was a monologue—polished, confident, and hermetically sealed. The production mistook repetition for rigor, unanimity for truth, and spectacle for inquiry. It was, in short, a missed opportunity.

Scientology has enemies. It raises questions. It deserves scrutiny. But scrutiny requires more than a predetermined script and a cast of familiar antagonists. It requires curiosity, humility, and the willingness to hear from those who do not fit the narrative. France 5 chose otherwise.

The outcome was a beautifully lit, professionally edited echo chamber, but still an echo chamber. Regardless of how dramatic the echoes may be, they do not qualify as journalism.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.