In Xi’s China, even atheism has good Feng Shui—as long as the state is the only geomancer in town.

by Massimo Introvigne

In 2018, just before launching “Bitter Winter,” I went on what would turn out to be one of my last lecture tours in China. Among the audience members were police officers responsible for suppressing “xie jiao,” which the Chinese insist on translating as “evil cults,” while a better translation is “organizations promoting heterodox teachings,” in short, religions the regime does not like. The officers solemnly claimed to be purely atheistic. But when the conversation shifted to Feng Shui, every hand shot up. Of course, they believed in it. Who wouldn’t? Bad Feng Shui could derail your career faster than a misquoted line from Marx.

I remembered this moment while reading Singapore Management University’s Professor Andrew Stokols’ insightful and subtly mischievous essay, “Feng Shui: Between Spirituality and State Legitimation,” published in “Sinocities.” Stokols presents a paradox that is distinctly Chinese, rich in history, and politically revealing: the Chinese Communist Party has spent decades denouncing Feng Shui as a feudal superstition. Still, it now uses a cleaned-up version to justify its grand urban and environmental projects. As Stokols notes, the CCP denounces Feng Shui as a superstitious remnant of the past that must be purged from the party ranks, all while promoting a “light” version to provide a logic of legitimation for massive state-led urban and environmental projects.

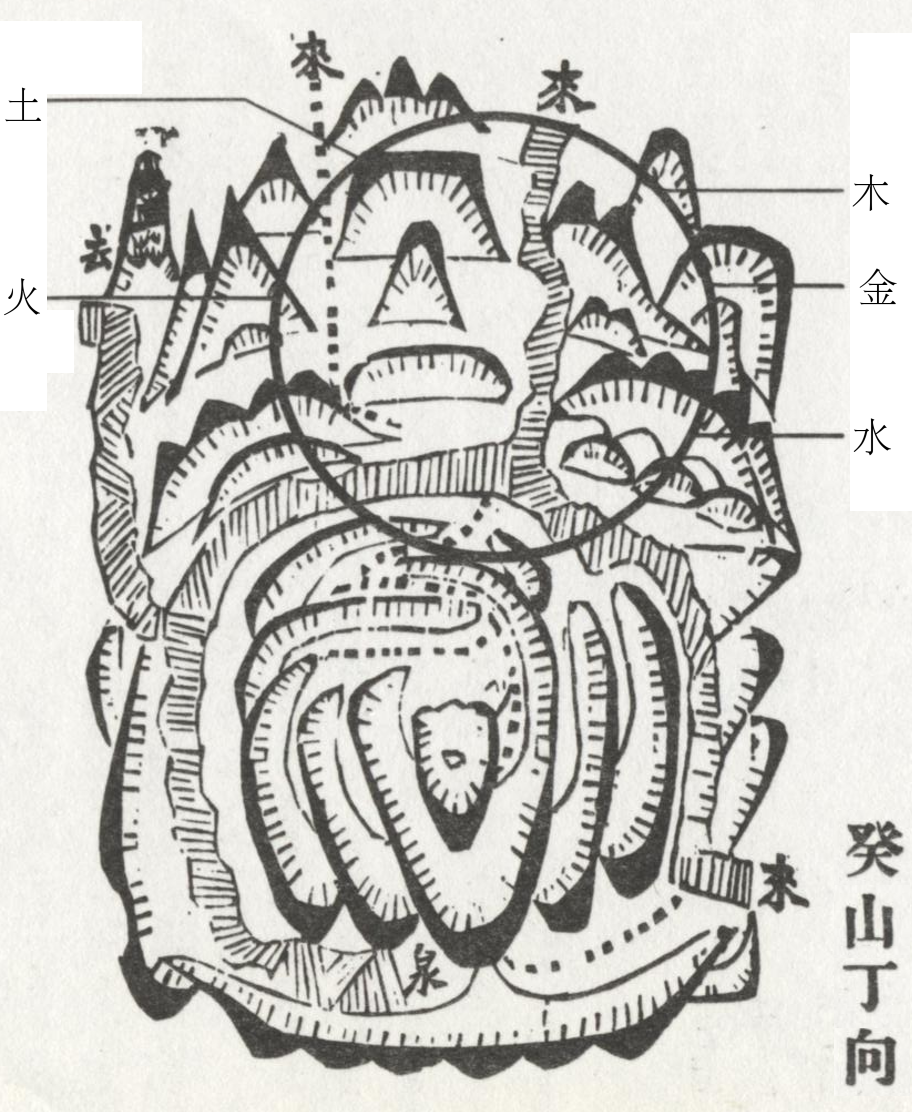

Feng Shui, once hunted as an “Old Custom,” has withstood campaigns, purges, and the Cultural Revolution’s destruction of ancestral graves. It has reemerged not as a folk practice but as a language of state power—an ecological Esperanto fluently spoken by planners, cadres, and, it seems, Xi Jinping himself. Stokols argues that Feng Shui has been “absorbed and rearticulated,” translated into modern ideas of environmental protection and technocratic planning. The Party attempted to kill it but ended up domesticating it instead.

This duality—superstition for the public, “excellent traditional culture” for the state—is the core of Stokols’ argument. Officials who consult geomancers may be purged for ideological impurity. Stokols reminds us that cabinet ministers like Zhou Yongkang and Li Jinzao faced disciplinary action for engaging in “superstitious activities.” Yet Xi Jinping simultaneously promotes “excellent Chinese traditional culture” as a source of national legitimacy. The approach is straightforward: remove ancestral spirits from Feng Shui, preserve the mountains and water, and voilà—geomancy becomes urban planning with Chinese characteristics.

In this “light” version of Feng Shui, mountains become “ecological spines,” rivers become “cultural corridors,” and the ancient concept of “longmai”—dragon veins—turns into a respectable planning term. The state, having failed to eradicate Feng Shui, now employs it to explain why a new district must align with a mountain peak or why a central axis must run exactly north-south. It is geomancy without ghosts, mysticism without mystics—a spiritual tradition sanitized through the language of sustainability.

Stokols’ case studies highlight the architectural side of this paradox. Shenzhen’s Futian CBD, with its nine-square grid aligned to Lianhuashan Park, resembles a modern ritual city more than a business district. Guangzhou’s Baiyun District keeps its mountain ridge as an “ecological spine,” even though everyone knows it is also the city’s dragon vein. In Xiong’an, Xi Jinping’s grand project of a “second capital” meant to ease Beijing’s overcrowding faced a challenge: the site is low-lying and prone to flooding, contrary to classical Feng Shui recommendations. No matter, advisor Xu Kuangdi explained that the area sits directly south of Tanzhe Temple, an ancient site predating Beijing. Align the new city with the temple, and the dragon vein will sort out the rest. Stokols describes this as a “convenient post-facto rationalization,” which is an academic way of saying they made it up afterward.

Xi’an provides another dramatic example. Xi Jinping wanted there a branch of the National Archives of Publications and Culture, but it was built by demolishing lavish and probably illegal villas owned by local Party leaders, who were not pleased. Enter Feng Shui. The National Archives of Publications and Culture was built directly against the Qinling Mountains, aligned with a peak, with its placement justified by the mountain’s dragon vein. The message is clear: the central state, not local officials, is the rightful guardian of China’s natural and spiritual landscape. Xi Jinping used the Qinling Mountains as a moral test for cadres; now he employs them as a cosmic endorsement of state authority.

By the end of Stokols’ essay, Feng Shui appears not as a quaint remnant but as a tool of power. It is flexible, ancient, and surprisingly compatible with authoritarian modernity. The Party labels private practice as superstition while using its own version to adorn highways, skyscrapers, and entire cities. It’s a clever move: by controlling the interpretation of Feng Shui, the CCP controls the symbolic order of space itself.

Stokols concludes that Feng Shui’s adaptability makes it ideal for a state that seeks to appear both modern and deeply rooted in tradition. The Party has accepted that it cannot eliminate Feng Shui; instead, it has placed itself as the ultimate authority on how it should be used. In this “state-led logic of legitimation,” the layout of China’s cities becomes a map of political authority, leading back to Beijing.

Reading Stokols, I recalled the police officers from 2018, claiming atheism while adjusting their desks to face the right way. They weren’t hypocrites. They were simply navigating a country where the state bans superstition yet practices it, where ideology bends to mountains and rivers, and where even the most secular revolution eventually realizes that the dragon veins run deeper than Marx.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.