They have been detained since March under dire conditions and subjected to abuses. Amnesty International is campaigning to secure their release.

by A. Sahara Alexander

In the Arab Republic of Egypt (officially so named by the 1971 national Constitution), Islam was designated as the state religion by a 1980 amendment to Article 2 of the Constitution. “Islam,” Article 2 states in the official English version, “is the religion of the State and Arabic is its official language. The principles of Islamic Sharia are the main source of legislation.” The 1980 amendment significantly altered the original wording, changing Sharia from being “a main source” to “the principal source of legislation.” This formulation was retained in the Constitutions of 2012 and 2014, as well as in all subsequent amendments up to those adopted in 2019 and 2021.

In Egypt, Sunni Muslims constitute approximately 90% of the population. The proportion of the second-largest religious group, the Coptic Orthodox Church, is variously estimated, but around 10% is generally considered a reasonable median figure. Other minorities are also present, including several Orthodox and Catholic denominations, Protestant Christians, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Jews, Shi’a Muslims, “Quranists” (who accept only the Quran and reject the Hadith), members of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama’at, Bahá’ís, adherents of the Ahmadi Religion of Peace and Light (AROPL), and even that peculiar group of “religionists” whose “faith” is atheism.

Those religions that the state officially allows

This picture of Egypt’s religious landscape differs sharply from the legal reality. According to the Constitution, as stated plainly in Article 2, all legislation must align with Islam and Sharia—whatever that may mean in practice, given the debates and controversies surrounding the interpretation of Islamic law. Moreover, Article 7 recognizes Al-Azhar, the prestigious mosque-university complex, as “[…] the main reference for religious sciences and Islamic affairs. It is responsible for calling to Islam, as well as disseminating religious sciences and the Arabic language in Egypt and all over the world. The State shall provide sufficient financial allocations thereto so that it can achieve its purposes. Al-Azhar’s Grand Sheikh is independent and may not be dismissed.” In simple terms, the state requires Muslims to follow one doctrine and one interpretation of Islam—exclusively that sanctioned by Al-Azhar.

This means that in Egypt, the state determines who is—and which groups are—truly “Islamic.” Any individual or group that follows Islam in a manner different from the state-sanctioned version is considered outside the fold of Islam and therefore heretical.

In this context, Article 3 may appear puzzling or even contradictory: “The principles of Christian and Jewish laws are the main source of legislation for followers of Christianity and Judaism in matters pertaining to personal status, religious affairs, and nomination of spiritual leaders.” In practice, this provision serves to justify recognizing Islam and, to a lesser extent, Christianity and Judaism as the only “divine religions” sponsored (Islam) or permitted (Christianity and Judaism) by the state. All other beliefs are excluded from recognition and are treated as non-divine, heterodox, “cultic,” or disruptive.

Under this framework, Article 64 discriminates against religions by granting “absolute” religious liberty… only relatively: “Freedom of belief is absolute. The freedom of practicing religious rituals and establishing worship places for the followers of Abrahamic religions is a right regulated by Law”—that is, only for Islam, Christianity, and Judaism, and only under state control. All other groups are left in an ambiguous grey zone of non-recognition.

Non-recognized faiths

In reality, not only does the “absolute” religious liberty promised by the Constitution exist only on paper, but so does the relative liberty granted to recognized groups. Since religious communities seeking recognition must apply to the Department of Administrative and Religious Affairs at the Ministry of Interior, it is ultimately the state that decides whether a group poses a threat to national unity or social peace. As stated in a 2021 (and still valid) report by the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy, “Egyptian institutions do not officially recognize some religious minorities. As a result, these minorities do not receive a set of basic constitutional rights, most notably the freedom of religion, belief, opinion, and expression. In addition, their followers are subject to ongoing surveillance and prosecution on the pretext of their illegal activities.”

Courts have upheld decisions to deny or revoke recognition of certain groups, or to restrict the terms of recognition granted to others, routinely citing the protection of public order or state-sponsored religions—practically speaking, Islam.

Unrecognized groups, therefore, face legal invisibility, restrictions on their rights, and the constant risk of persecution. They cannot formally operate as religious organizations, hold public gatherings, build places of worship, or establish official cemeteries. In official documents, their adherents may be forced to list themselves as followers of one of the three recognized religions to avoid losing access to education, public services, and pensions—effectively requiring them to curtail their freedom as human beings to enjoy their rights as citizens. They face monitoring, harassment, prosecution, social discrimination, hate speech, and hostility—including from educational institutions and online—while being frequently summoned and questioned by the National Security Agency, Egypt’s main domestic security body.

The country report published by the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) in February 2025 describes a situation that, twelve months later, has only worsened.

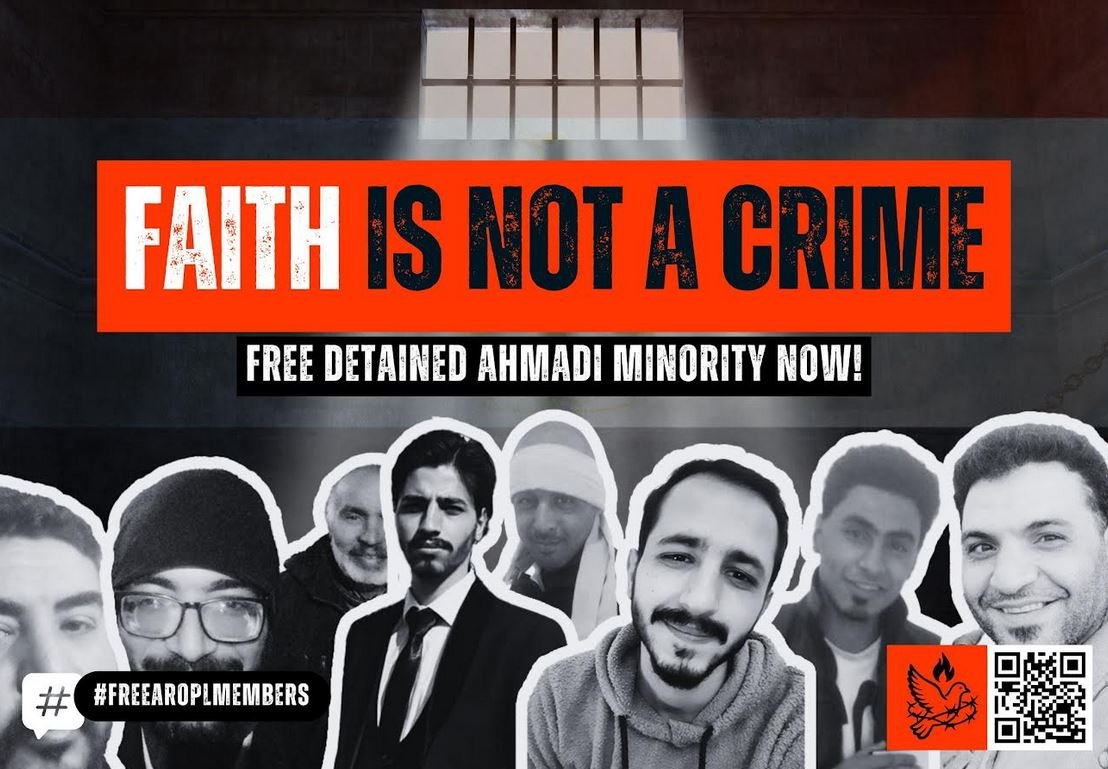

Detained for promoting a TV station

This deterioration is illustrated by the case of several believers belonging to one such unrecognized group, the Ahmadi Religion of Peace and Light (AROPL). Their case arose after the publication of the latest USCIRF report and is documented in two Amnesty International reports dated April 24, 2025, and October 21, 2025.

AROPL (not to be confused with the Sunni-derivative Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama’at) was established in 1999 and recognizes Iraqi Imam Ahmed al-Hassan as its divine guide. His followers are divided into various rival groups. A Shia-derivative messianic millenarian new religious movement, AROPL’s beliefs center on the “Mahdi,” a messianic figure in Islamic eschatology believed to appear at the end of times to restore justice and true religion. AROPL was founded by Egyptian American religious leader Abdullah Hashem Aba al-Sadiq, and some of his adherents appear on USCIRF’s list of persecuted individuals.

On February 27, 2025, a small group of AROPL members hung a banner on a pedestrian bridge in Giza advertising the frequency of “Zahra al-Mahdi” (“The Mahdi Has Appeared”), a satellite television channel affiliated with AROPL, featuring a picture of its leader.

Following this action, on March 8, 2025, Egyptian security forces arrested Ali Alhadary, releasing him later the same day without charge, according to Imran Ali, the United Kingdom–based AROPL bishop for Egypt. Police then used Alhadary’s Telegram account to access a group of fellow believers and tracked down 14 additional AROPL members, arresting them in various districts and cities across Egypt. The cases of three of them—Omar Mahmoud Abdel Maguid, Hazem Saied Abdel Moatamed, and Ahmed Mohammed Al-Tenawi—and that of a fourth, Hussein Mohammed Al-Tenawi, are particularly noteworthy.

Other AROPL members arrested, guilty of nothing

Omar Mahmoud Abdel Maguid was arrested on March 10 after a violent raid on his home in Cairo. Police later searched the house again, attempting to arrest his brother-in-law, Hazem Saied Abdel Moatamed. According to Moatamed’s family, he initially managed to flee but was arrested on March 13 in 10th of Ramadan City, Sharqia Governorate.

On March 11, plainclothes officers arrested Ahmed Mohammed Al-Tenawi and his brother, Hussein Mohammed Al-Tenawi, at their home in 6th of October City, Giza Governorate. According to a family member, the officers did not present an arrest warrant. The two brothers are Syrian citizens who had fled to Egypt seeking asylum from persecution of Shias in Syria and the deteriorating conditions in their home country. They are registered with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (“Bitter Winter” has seen their registration certificates).

Ahmed Mohammed Al-Tenawi was held incommunicado at the 6th of October City First Police Station for 28 days before being unlawfully deported to Syria on April 9. Once back, he was forced into hiding in fear for his life, and neither Amnesty International nor AROPL has had further contact with him. His brother, Hussein, was not deported because he is considered the leader of the group, as AROPL members used to gather at his home.

Instead, police kept him, along with Omar Mahmoud Abdel Maguid and Hazem Saied Abdel Moatamed, in custody at undisclosed locations for periods ranging from 29 to 34 days before bringing them before a prosecutor. The families submitted complaints on March 25 but received no response.

On April 10 and 13, the men were brought before the Supreme State Security Prosecution for interrogation, without being allowed to choose their own lawyers. They were questioned alongside a dozen other AROPL members on charges of “joining a group established in violation of the Constitution and the law,” according to Amnesty International.

Their health is a matter of grave concern. Before detention, Hussein Mohammed Al-Tenawi suffered from a cervical disc injury and chronic sinusitis requiring therapy and surgery; these conditions have significantly worsened. Omar Mahmoud Abdel Maguid suffers from high blood pressure and recurrent headaches. All three have been subjected to extremely harsh detention conditions, including severe cold in their cells, causing recurrent respiratory illnesses. They are not receiving adequate medical treatment. They are also provided with a grossly inadequate amount of food: a few spoons of rice and pieces of bread.

Torture: heinous abuses

Imran Ali reported that at least four other AROPL members were arrested throughout March in separate incidents, three of whom managed to send messages before their arrests; he has not heard from them since. Testimonies also describe particularly heinous forms of persecution—torture—documented by Amnesty International.

On April 22, Hussein Mohammed Al-Tenawi informed his lawyers that National Security Agency officers tortured him while he was held at the agency’s headquarters. He added that conditions in 10th of Ramadan Prison were poor, that he was not receiving sufficient food, and that he was denied medical care. Omar Mahmoud Abdel Maguid and Hazem Saied Abdel Moatamed testified that they had been subjected to similar torture, including electric shocks.

This information was not made public immediately because the detainees were held in undisclosed locations, and no information about their whereabouts leaked during their enforced disappearance. Only after nearly a month of isolation were they moved from what amounted to a “dungeon” to a more regular prison, where they gradually began recounting the mistreatment, abuses, and beatings they had endured. Amnesty International initially reported torture of three detainees; recent updates collected by “Bitter Winter” increase that number by at least one or two more.

“Bitter Winter” also obtained information indicating that Egyptian authorities have sent scholars from state Islamic institutions to the detainees in prison, tasked with “re-educating” them and pressuring them to recant their beliefs. The scholars promised quick release in exchange for renouncing their faith. None complied, and these visits continue. The detainees are kept isolated from other inmates to prevent them from sharing their beliefs.

The entire situation constitutes a monumental and gross violation of human rights. The motivations behind the arrests are futile and absurd. In a country that claims to be democratic, a person was arrested for displaying a banner about a religious TV station. Others were detained simply for belonging to the same religious group. In many cases, no official charges were brought. An asylum seeker was forcibly repatriated to a dangerous homeland. The pretrial detention periods are absurdly long and unjustified. The detainees have been subjected not to trial but to isolation, abduction, harassment, violence, abuse, and torture. Their lawyers, once appointed—despite considerable obstruction—have not been granted access to their case files.

Amnesty International has launched a campaign on behalf of the 14 AROPL members arrested and tortured in Egypt since March. Unfortunately, the authorities in Cairo continue to detain them without responding to the campaign.

While these innocent individuals continue to suffer, it is urgent to amplify Amnesty International’s mobilization through all lawful means, including writing letters to Egyptian authorities and embassies.

Uses a pseudonym for security reasons.