When a streaming series becomes a tribunal, it is time for the international human rights community to take notice.

by Massimo Introvigne

The United Nations Human Rights Council is not easily shocked. It has heard testimonies from war zones, authoritarian regimes, and places where the rule of law is more aspiration than reality. Yet at its 61st session in Geneva, something unusual happened: an ECOSOC‑accredited NGO, Coordination des associations et des particuliers pour la liberté de conscience (CAP‑LC), submitted a written statement warning that a global entertainment product—a Netflix documentary—has helped ignite a transnational human‑rights crisis.

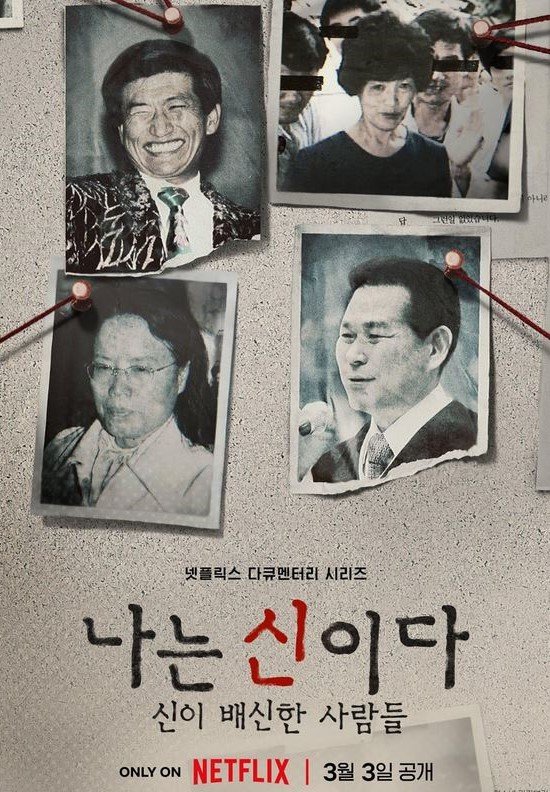

The statement, titled “Systematic Persecution and Erosion of Minority Rights: The Case of the Christian Gospel Mission (Providence),” is an unsettling account of what happens when commercial storytelling collides with the rights of a religious minority. CAP‑LC begins by noting that the founder of the Christian Gospel Mission (CGM), also known as Providence, “has been sentenced in South Korea on various sexual abuse charges.” Members believe him innocent, but CAP‑LC stresses that “it is not the role of CAP‑LC to take a position on this issue.” Their concern is elsewhere: the discrimination, stigma, and violence inflicted on ordinary believers who are not accused of any crime.

According to the statement, the crisis escalated dramatically after the release of a Netflix documentary in 2023 and its sequel in 2025. What began as entertainment “created for profit” metastasized into a “digital witch hunt,” where algorithmic boosting and sensational framing encouraged online mobs to treat CGM members as fair game. CAP‑LC describes a “stark clash between commercial free expression and the protections outlined in the ICCPR,” noting that “the presumption of innocence, the right to privacy, the right to work, the right to education, and the right to freedom of religion have all suffered systematic and devastating losses.”

The testimonies collected by CAP‑LC reveal a pattern of guilt by association so pervasive that sociologists would recognize it instantly. Ordinary believers—students, civil servants, caregivers, small business owners—found themselves punished for allegations directed at someone else. The result, CAP‑LC writes, is “social death,” a condition in which individuals lose their identity, dignity, and safety.

Download the written statement in PDF (date of general distribution subject to change).

In Taiwan, where the CGM has roughly 4,500 members, the persecution spread with viral speed. Anonymous forums and social‑media algorithms turned doxxing into a public sport. Names, photos, workplaces, and home addresses were circulated without consent, transforming private citizens into targets. In South Korea, more than 160 sworn statements document a similar pattern: exclusion, harassment, and the replacement of due process with the verdict of the digital mob. The “court of public opinion,” CAP‑LC warns, has become a parallel justice system—one that “convicts without evidence and punishes without limits.”

Economic destruction has been one of the most visible consequences. Victims describe a “digital scarlet letter” that online vigilantes use to mark businesses for ruin. CAP‑LC recounts cases of café owners, restaurateurs, crafts instructors, caregivers, and shopkeepers whose livelihoods collapsed after coordinated review‑bombing, doxxing, and boycotts. Even academia has not been spared: an assistant professor on the island, praised by colleagues for his teaching, saw his contract quietly dropped after his affiliation was exposed on an anonymous forum.

Women have faced a particularly vicious form of persecution. CAP‑LC details how misogyny, religious prejudice, and sexual slander have fused into a toxic narrative portraying CGM women as “victims,” “brides,” or “sexual slaves.” Anonymous platforms in Taiwan have become hubs for cyber‑violence, where female pastors are subjected to obscene captions, altered images, and degrading commentary. In South Korea, the trauma is echoed in personal accounts. Strangers asked one woman whether she had been “exploited.” At the same time, another developed severe stress‑induced illness after her husband, influenced by media narratives, began calling her a “sex slave” and monitoring her communications. These cases show how media narratives can empower abusive partners and turn homes into sites of violence.

Children, who bear no responsibility for their parents’ beliefs, have also become casualties. CAP‑LC reports that in Taiwan, a teacher showed a restricted trailer of the documentary to third graders, triggering fear and enabling bullying. In South Korea, children have been mocked by peers and educators, forced to leave schools, or too frightened to attend. One father described how his daughter came home terrified after seeing defamatory banners; another reported that his children were called “heretics” and shunned. A high‑school freshman said her excitement for the new school year was shattered when classmates labeled her religion “disgusting.” These incidents reveal a profound failure of societal protections meant to shield minors from discrimination.

The breakdown of private life is equally alarming. CAP‑LC describes how the documentary series “weaponized family anxieties,” leading to estrangement, conflict, and even violence. Members have been cut off by siblings, rejected by parents, and subjected to deprogramming and forced “exorcisms.” Marriages have deteriorated as spouses, influenced by media narratives, forbid church attendance or engage in verbal abuse. The right to family life, CAP‑LC argues, has been eroded by a climate of suspicion and fear.

The psychological toll has been immense. Depression, anxiety, and insomnia are widespread. But the suffering has also manifested physically. CAP‑LC documents cases of severe pityriasis rosea, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, sudden hearing loss, shingles, and life‑threatening autoimmune flare‑ups—all triggered or worsened by stress. These conditions, the statement notes, are “clear evidence of the crisis’ severity and underscore the breach of the right to health.”

The statement concludes that the treatment of CGM members violates Articles 18 (freedom of religion), 12 (privacy), and 7 (protection from discrimination) of the UDHR. It also highlights a regulatory vacuum: traditional broadcasters are bound by ethical guidelines, but global streaming platforms operate with far fewer constraints. The release of the 2025 sequel, despite documented risks, raises urgent questions about corporate responsibility. Victims describe this “cold‑blooded, cruel form of media violence” as “worse than war,” because it encourages the public to act as “judge, jury, and executioner.”

CAP‑LC calls to investigate institutional discrimination in Taiwan and in South Korea, condemn guilt‑by‑association practices, and address the ethical duties of global streaming platforms. Media narratives, it insists, should not taint legal processes or undermine the dignity of minority groups.

In the case of CGM, what began as entertainment has spiraled into a human‑rights crisis. And the fact that this issue has now reached the United Nations is itself a warning. When commercial media can trigger “social death,” destroy livelihoods, fracture families, and traumatize children, the problem is systemic and transnational. And it is severe enough that an ECOSOC‑accredited NGO has felt compelled to bring it before the world’s highest human‑rights body.

The persecution of CGM members is no longer a story confined to Korea or Taiwan. It is now a matter of international concern—because the scars left by this “digital scarlet letter” may last far longer than the documentary that helped create it.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.