Judicial Day reminds us that justice is not a one-time act but a process that requires coherence, institutional courage, and a willingness to repair the harm done.

by Karolina Maria Kotkowska*

*A paper presented at the 2026 Judicial Day Forum, “State Obligations under the Two International Human Rights Covenants—Taking the Tai Ji Men Fabricated Case as an Example,” National Taiwan University, Taipei, January 11, 2026.

Judicial Day, observed in Taiwan on January 11, carries both symbolic and practical significance. It recalls the moment when the Republic of China regained full judicial sovereignty and affirms a constitutional order in which the law is meant to apply equally to all, without exceptions or privileged categories.

Judicial Day reminds us that the rule of law is not just about having statutes and courts. It depends on the state’s ability to deliver real justice. It is a moment to reflect on whether legal mechanisms genuinely lead to the adequate protection of human rights, and whether public institutions are capable of correcting their own errors, once those errors have been clearly identified.

In this sense, Judicial Day is not about celebrating institutions; it’s a call for accountability throughout the entire system. That responsibility lies not only with the courts, but also with public administration and all state bodies involved in implementing the law. A state governed by the rule of law does not end its duty with the issuance of a final judgment; its quality is also measured by whether the consequences of that judgment are consistently respected and carried out by other institutions.

Judicial Day promotes a crucial question: what happens when the law has been correctly applied, when innocence has been unequivocally established, yet an individual or a community continues to bear the consequences of state action? According to the international human rights covenants that Taiwan acknowledges, the right to a fair trial is essential, but so is the right to an effective remedy and genuine restoration of violated rights.

Judicial Day reminds us that justice is not a one-time act but a process that requires coherence, institutional courage, and a willingness to repair the harm done. For this reason, today’s observance of Judicial Day is less a reflection on the past than a question addressed to the present and the future: does equality before the law signify only formal recognition, or does it also entail real and adequate protection?

The Tai Ji Men case illustrates a situation in which the judiciary functioned properly, while the system as a whole failed to deliver justice. After many years of criminal proceedings, the highest court unequivocally acquitted Tai Ji Men of all charges, confirming that there had been neither fraud nor tax evasion.

Despite this ruling, administrative authorities continued to maintain specific tax assessments based on the same assumptions that had already been rejected, leading to further sanctions and enforcement measures. As a result, a case that had been resolved in court continued at the administrative level, revealing a tension between a final judgment and its implementation by the state.

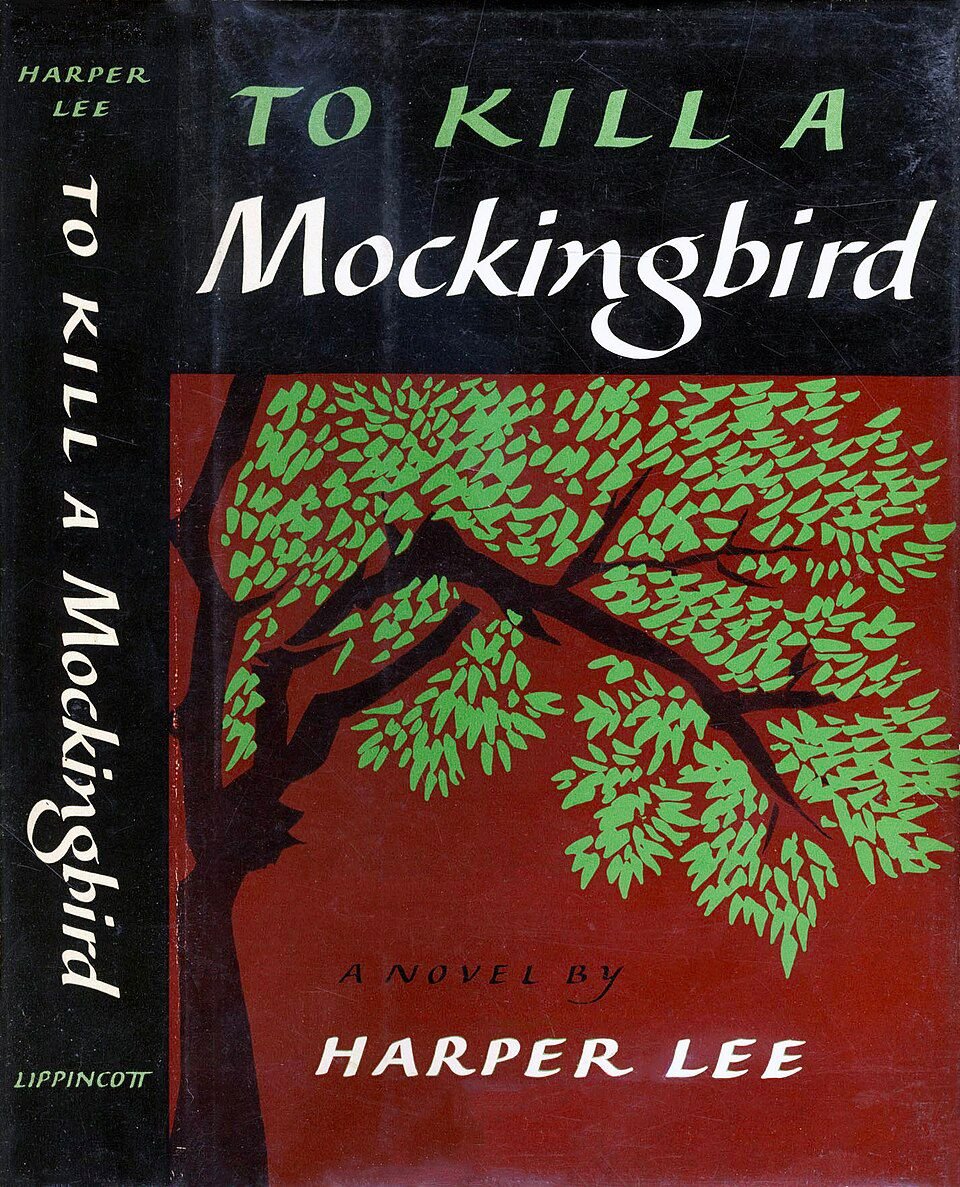

Systemic injustice has been the subject of countless works that have entered the canon of world literature. One such example is “To Kill a Mockingbird,” published in 1960 by Harper Lee. In 2007, Lee was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom—the highest civilian honor in the United States—for her contribution to literature and to the public debate on social values, including justice.

In the United States, this distinction is reserved for individuals whose work is deemed to make an exceptional contribution to the public good. The fact that it was awarded for “To Kill a Mockingbird” emphasizes that drawing attention to systemic inequality and the selective operation of the law may itself be recognized as serving the public interest.

In “To Kill a Mockingbird,” injustice stems not from a lack of law but from the selective operation of the system. The same legal community can be relentless toward one innocent person while offering protection to another deemed worthy. The novel illustrates that the issue lies not in the existence of legal mechanisms themselves, but in who the system chooses to protect at any moment, and whom it neglects despite clear facts.

This literary example helps us understand injustice as a phenomenon within a larger system, not as something that needs to be codified in law or result from a faulty judgment. It can arise when institutions operate in disconnected ways, when responsibilities are spread across various authorities, and when strict adherence to formalities overshadows a genuine willingness to address the aftermath of earlier state actions. Under these conditions, justice is not openly denied; it is stifled, leaving victims in a state of ongoing and hard-to-overcome inequality before the system.

Sadly, this situation persists today in many contexts. The Tai Ji Men case, which has continued for more than two decades, is a clear example.

On this Judicial Day, it is worth recalling the second storyline of “To Kill a Mockingbird,” where the system ultimately protects an innocent person. However, Tai Ji Men is still waiting for justice that is not only proclaimed but also effectively realized; so far, that justice remains frustratingly delayed.

Karolina Maria Kotkowska is an Assistant Professor in the Centre for Comparative Studies of Civilizations, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland. She holds PhD in Philosophy and works on her PhD in Sociology. She specializes in New Religious Movements and Western Esotericism in Central and Eastern Europe.