Puccini’s “Madama Butterfly” alludes to the Inequal Treaties in Japan. Judicial Day in Taiwan commemorates the end of similar treaties in China. It is also an opportunity to call for justice for Tai Ji Men.

by Massimo Introvigne*

*A paper presented at the 2026 Judicial Day Forum “State Obligations under the Two International Human Rights Covenants—Taking the Tai Ji Men Fabricated Case as an Example,” National Taiwan University, Taipei, January 11, 2026.

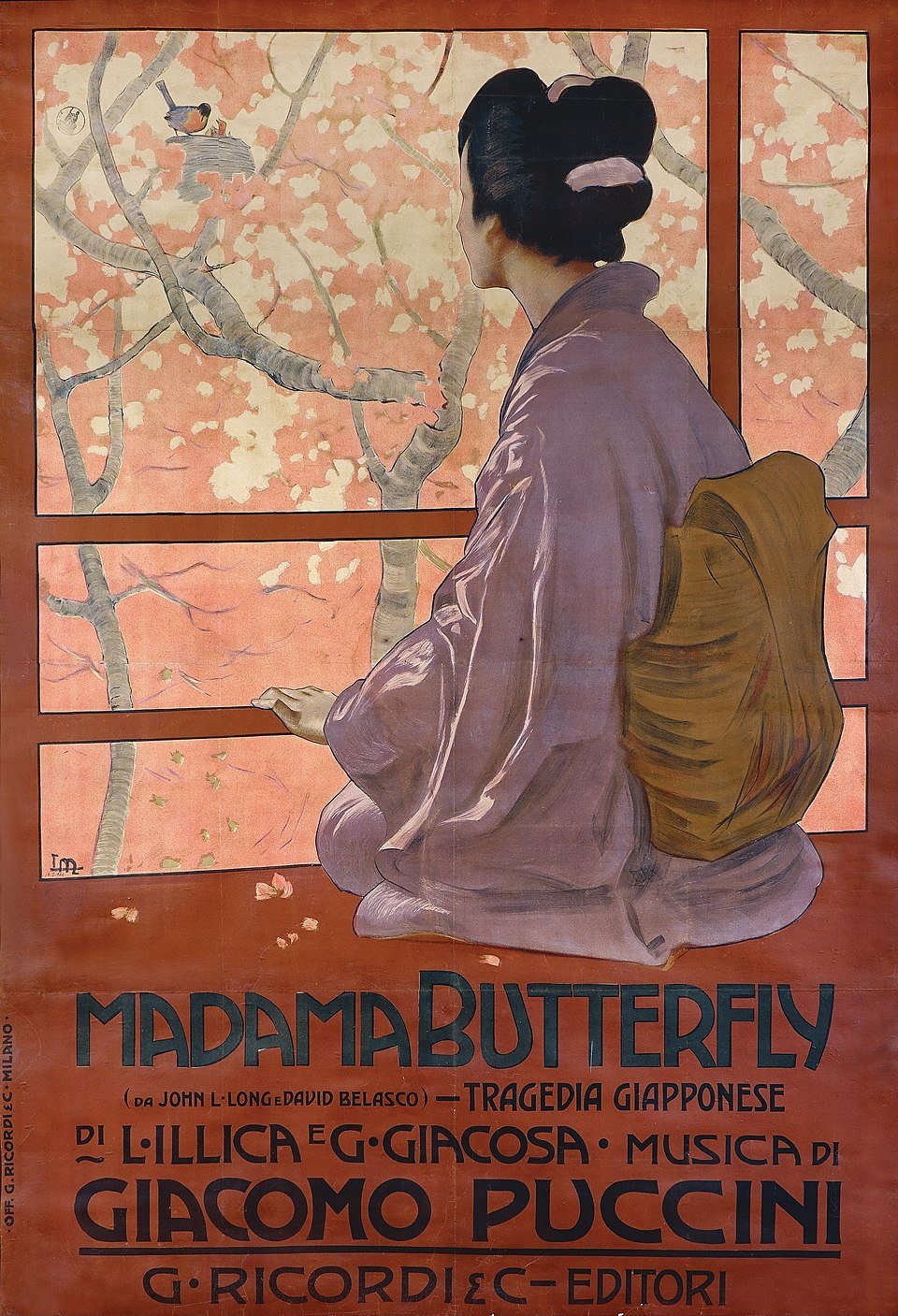

It is a joy and an honor to speak to you on Judicial Day. As some of you know, I come from Tuscany, from a quiet corner of Italy not far from Torre del Lago Puccini—the lakeside town where the great composer lived, dreamed, and where he now rests. Every summer, on the open‑air stage that rises from the water, Puccini’s operas return to life. And among them, my favorite has always been “Madama Butterfly,” a work that, perhaps unexpectedly, carries a profound connection to Taiwan’s Judicial Day.

Judicial Day commemorates a moment when the Republic of China reclaimed its legal dignity. For more than a century, China had been forced to sign the so‑called Unequal Treaties, agreements imposed by Western powers that stripped China of its judicial sovereignty. Foreigners lived in enclaves where Chinese law did not apply. They were judged only by their own consuls, under their own rules. It was a system built on humiliation, on the idea that some people were above the law of the land in which they lived.

On January 11, 1943, the United States and the government of Chiang Kai‑shek signed a treaty ending these privileges. When the Republic of China later established its legal system in Taiwan, this date— January 11—became a symbol of restored justice, a reminder that no nation should live under a system where some are protected and others abandoned.

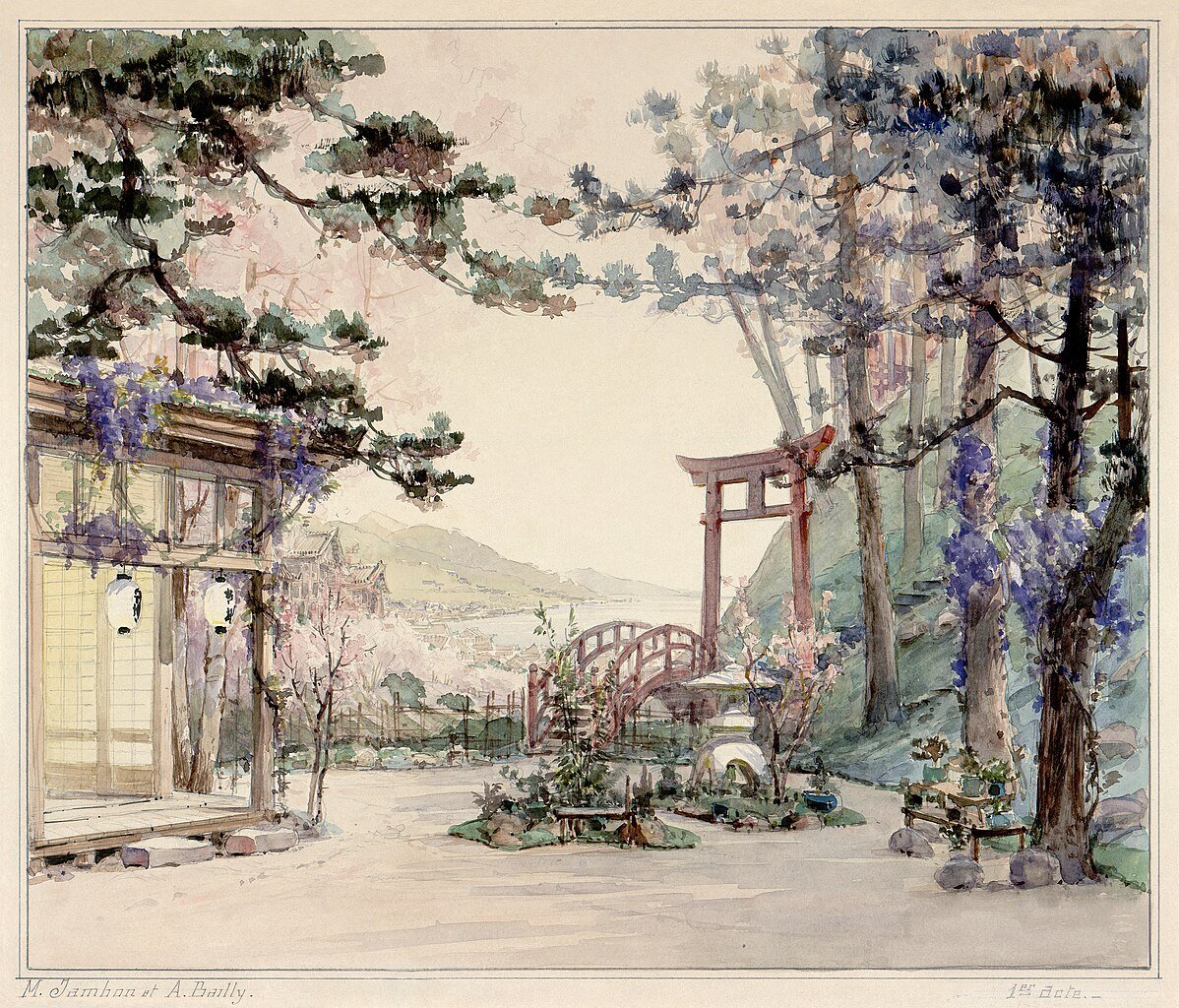

But this story is not only Chinese. Japan, too, had signed similar Unequal Treaties. And this is where Puccini’s Butterfly enters the picture.

The opera tells a story as old as humanity: a young woman, full of hope, meets a man who does not deserve her. Pinkerton, an American naval officer, takes a liking to the beautiful young Butterfly. He does not tell her he is already married. He goes through a “marriage” ceremony that is, in truth, illegal and bigamous. Then he disappears, returns to his American wife, and leaves Butterfly alone and pregnant. When he finally comes back—with his real wife—and Butterfly realizes she was never meant to be part of his life, she takes her own.

Why could Pinkerton behave with such impunity? Because he was not subject to Japanese law. He could not be punished by it. He was protected by the extraterritorial jurisdiction of the American consul—a man named Sharpless. In Puccini’s opera, Sharpless is even a decent man. He urges Pinkerton to act honorably. But he cannot enforce justice. He can only advise. The system itself is broken.

This is why Butterfly’s tragedy is deeply political. It is the story of a world where law does not protect the vulnerable, where bureaucratic structures allow injustice to flourish.

Both China and Japan eventually abolished the Unequal Treaties. And for this reason, Taiwan still celebrates Judicial Day—a day that symbolizes the end of foreign privilege and the restoration of legal equality, which also happened in Japan. Today, Butterfly would be able to walk into a Japanese court and demand justice.

But abolishing unjust systems does not automatically abolish injustice. Because injustice is not only a matter of law. It is a matter of how bureaucrats interpret the law, how officials use their power, how institutions treat the people they are meant to serve.

While Taiwan is rightly proud of its Judicial Day, the unresolved Tai Ji Men case stands as a painful reminder that a spirit of injustice can survive even after the laws have changed. It survives in the shadows of bureaucracy, in the stubbornness of officials who refuse to admit mistakes, in the machinery of taxation and administration that sometimes forgets the human beings standing before it.

For nearly three decades, Tai Ji Men has lived with the consequences of this injustice—an injustice that has been recognized by courts, scholars, international observers, and countless people of conscience. And yet, the wound remains open. The harm remains unhealed.

Judicial Day should be a call to conscience, a reminder that the work of justice is never finished. It should inspire us to confront the injustices that still exist.

Tai Ji Men has shown extraordinary patience, dignity, and resilience. Its Shifu (Grand Master) and dizi (disciples) have turned suffering into peaceful resistance, injustice into moral clarity, and pain into a global movement for conscience. They have done what Butterfly could not: they have refused to surrender to despair.

A nation is not judged only by the laws it writes, but by the justice it delivers. Not only by the treaties it abolishes, but by the wrongs it chooses to correct. Not only by the freedoms it proclaims, but by the courage to confront its own mistakes. Taiwan has every reason to be proud of its democracy. But true pride comes not from ignoring injustice—it comes from correcting it.

This year, the year of the 30th anniversary of the beginning of the Tai Ji Men case, Judicial Day cannot be only a commemoration of the past; it should be a promise for the future. A promise that the spirit of Butterfly—the longing for dignity, fairness, and truth—will not be forgotten.

A promise that the injustice suffered by Tai Ji Men will one day be acknowledged, repaired—and finally laid to rest.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.