A report denounces a state that has failed to protect its citizens from religious extremism and from the excesses of its own security apparatus.

by A. Sahara Alexander

The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan’s (HRCP) report, “Caught in the Crossfire: Civilians, Security and the Crisis of Justice in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s Merged Districts” (Lahore: HRCP, 2025), reads like a tragic script for a play the state insists on performing over and over again. The title, “Caught in the Crossfire,” is apt: civilians are literally and figuratively trapped between militants who kill in the name of religion and a government that kills in the name of security.

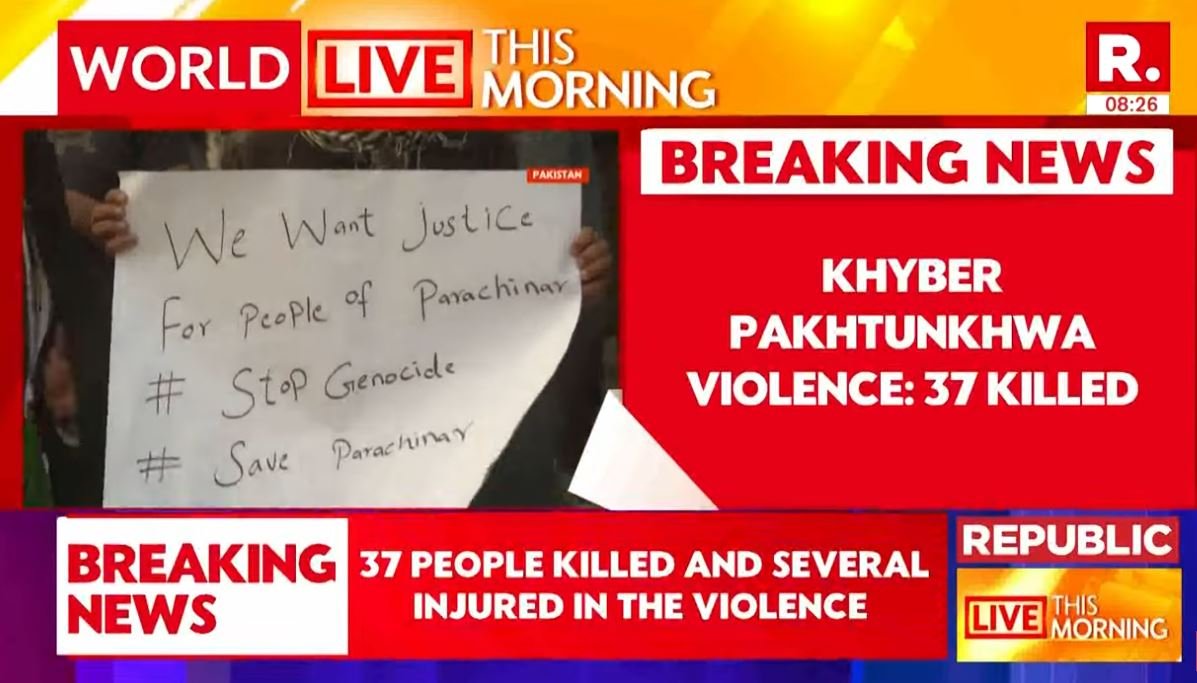

The statistics alone are chilling. In July 2025, 82 militant attacks nationwide—two-thirds of them in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. By September, 45 attacks in the province killed 54 people, while “security forces reportedly carried out 22 operations… killing 88 militants” but also 24 civilians. The arithmetic of counterterrorism in Pakistan has always been brutal: militants dead, civilians dead, justice dead.

The HRCP mission interviewed politicians, police, tribal elders, lawyers, and journalists. What emerged was a portrait of a province where the ghosts of past policies—strategic depth in Afghanistan, resettlement of militants, secret deals with the Taliban—haunt every attempt at peace. The provincial president of the Awami National Party (ANP) noted that “the security situation was significantly more precarious than generally perceived,” with ISIS now active in the province. Another politician admitted that militants and “copycat” criminal gangs have made Waziristan and Bajaur so dangerous that civil servants hide by late afternoon.

Religious extremism is the unspoken protagonist here. Tribal elders and peace advocates—those who dare to challenge militant narratives—are systematically slaughtered. The killing in July 2025 of Maulana Khan Zeb in Bajaur, a respected advocate for peace, epitomizes the collapse of traditional mechanisms of social cohesion. His murder, despite security camera evidence, remains unpunished. When elders are silenced, the vacuum is filled by militants preaching fear and sectarian hatred.

The state has responded through internment centres, enforced disappearances, and the notorious Actions (in Aid of Civil Power) Ordinance 2019. HRCP rightly calls this a “grave violation” of constitutional protections. Families of missing persons recount torture, intimidation, and bodies returned under the cover of night. The government insists there are “only 961” missing persons; activists say closer to 8,000. Numbers aside, the practice itself is a stain on any claim to democracy.

Meanwhile, the Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement (PTM), one of the few voices consistently advocating peace, is arbitrarily banned. Its leaders are jailed under terrorism laws, while sedition charges under Section 124‑A of the Penal Code are wielded against journalists and activists. In Pakistan, it seems, speaking against extremism is treated as extremism.

The HRCP report also exposes the economic underbelly of the conflict: mineral wealth in Waziristan, Kurram, and Khyber. Communities suspect military operations are often less interested in security than in clearing land for mining concessions. As one legislator put it, “significant reserves of lithium reportedly exist in Kunar and Kurram, and copper in North Waziristan.” When bombs fall, they may be clearing the way for bulldozers.

The recommendations are a catalogue of common sense unlikely to be accepted in the Pakistani context: consult communities before military operations, repeal unconstitutional ordinances, shut down internment centres, stop enforced disappearances, protect political dissent, investigate killings of peace advocates, and—most “radical” of all—treat citizens as more than collateral damage. HRCP insists “The state must reaffirm, in policy and practice, that the lives and rights of its people are non-negotiable.” But perhaps Islamabad never got the memo.

In the end, the report reflects a state that has failed to protect its citizens from religious extremism, was unable to restrain its own security apparatus, and failed to deliver justice. The militants thrive on ideology; the government thrives on impunity. And civilians, as always, are caught in the middle—crossfire as policy, crossfire as destiny.

Uses a pseudonym for security reasons.