A book suggests that legends about vanished short-statured beings may have a kernel of truth—and challenge the Han-centered narrative of the history of China.

by Massimo Introvigne

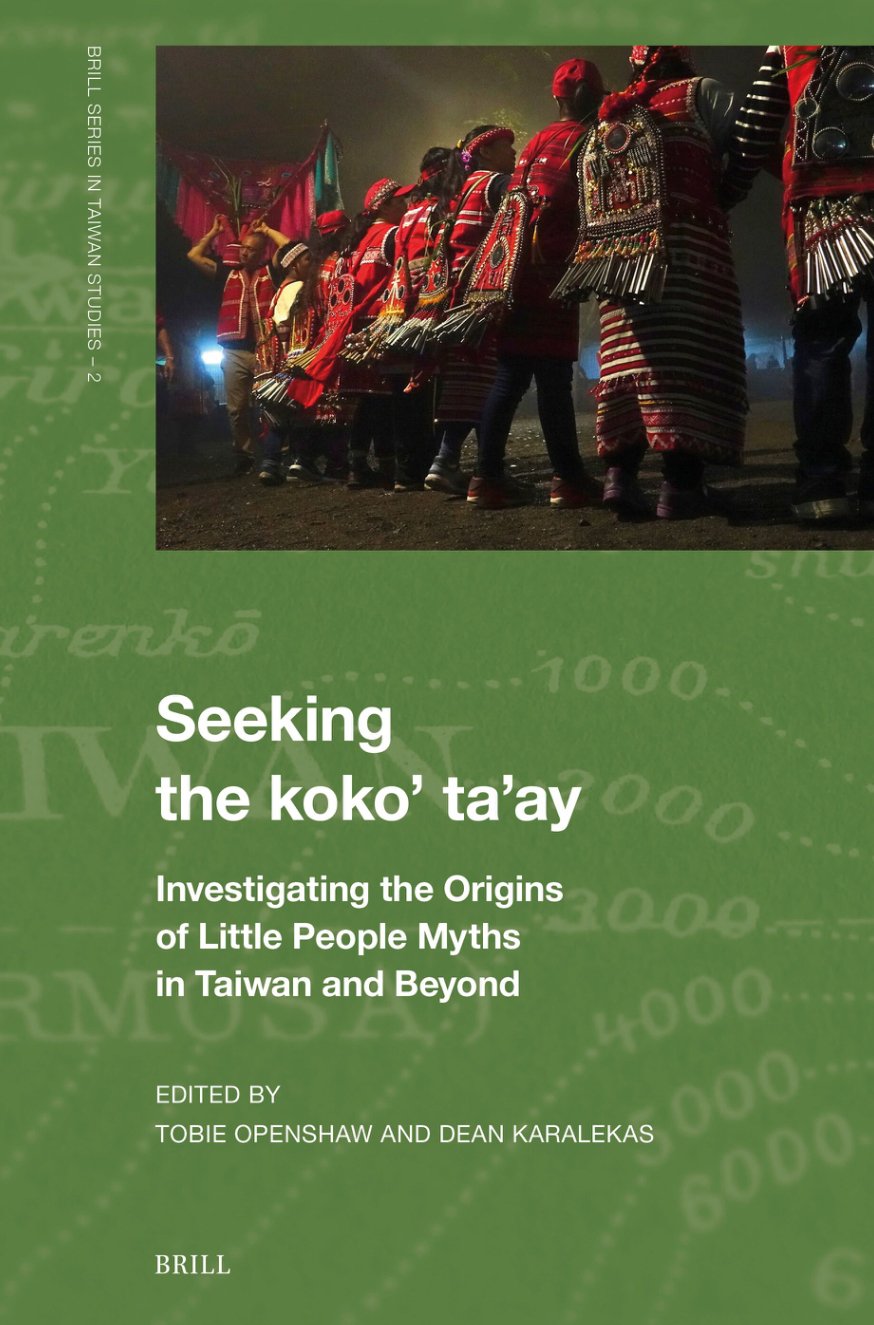

In “Seeking the Koko’ Ta’ay: Investigating the Origins of Little People Myths in Taiwan and Beyond” (Leiden: Brill, 2024), editors Tobie Openshaw and Dean Karalekas have assembled a scholarly constellation that glows with myth, memory, and political defiance. The book is a multidisciplinary inquiry into the recurring legends of short-statured beings—known among the Saisiyat as ta’ay—who once lived in Taiwan, China, and across the Austronesian world. But this is no mere folklore compendium. It’s a challenge to nationalist historiography, a celebration of Indigenous epistemologies, and a subtle act of resistance against the Han-centric narrative of Chinese antiquity.

The book invites readers to treat myths as maps, tracing the contours of cultural memory across Taiwan, China, and the Pacific. The authors argue that the legends of the ta’ay and their counterparts—the veli of Fiji, the MKsingut of Atayal lore, and the misinsigots of Paiwan tradition—may encode real encounters with Negrito populations, the so-called “First Peoples” of the region. These myths, he suggests, are not quaint tales but mnemonic devices, preserving the memory of Paleolithic foragers who once roamed Taiwan’s grassy plains before it became an island—and parts of present-day Mainland China too.

This thesis is politically potent. If Negritos once inhabited Taiwan and parts of southern China, then the Han narrative of uninterrupted civilizational dominance is fractured. The book thus becomes a quiet torpedo aimed at Chinese propaganda, which often erases non-Han histories in favor of a monolithic past.

The book’s first section, “The Science,” includes Paul Jen-kuei Li’s linguistic survey of the myths. Li revisits his earlier work, noting the absence of linguistic evidence to confirm the ta’ay’s existence and the tantalizing possibility that recent archaeological finds, like the Xiaoma Lady, may change that. The Xiaoma Lady, discovered in a cave on Taiwan’s east coast, is a 6,000-year-old skeleton with cranial features and stature reminiscent of Negrito populations.

Hsiao-chun Hung, Hirofumi Matsumura, and Mike T. Carson expand on this, linking the Xiaoma Lady to pre-Austronesian populations. Their work suggests that the ta’ay legends may be based on real, short-statured inhabitants who greeted Neolithic newcomers with knowledge and ritual. Roger Blench adds a linguistic twist, arguing that Formosan languages contain substrate lexicons—loanwords for endemic animals—that may have come from these earlier peoples. If true, this would mean that Austronesian settlers absorbed not just land but language from their predecessors.

P. Bion Griffin then zooms out, offering an ethnographic overview of Negrito populations across Southeast Asia. He highlights the Onge of the Andaman Islands, the Batek of Malaysia, and the Agta of Luzon, noting their genetic links to Denisovans and their status as cultural ancestors of the region. The implication is clear: the ta’ay are not just Taiwanese—they are part of a pan-Pacific memory of diminutive, wise, and often marginalized peoples.

The second section, “The Mythology,” is where the book truly sings. Liu Yu-ling’s chapter on the Saisiyat’s ta’ay legend offers tantalizing ethnographic storytelling. She traces the myth’s evolution and its ritual instantiation in the PaSta’ay festival, a biennial ceremony that reenacts the tragic history of the ta’ay—their generosity, extermination, and their spiritual persistence. The festival is not just a cultural event; it’s a ritual of remembrance, a political act, and a form of Indigenous historiography.

Lancini Jen-hao Cheng’s chapter on ritual tools and songs deepens this analysis. He lists, among others, the red-and-white Sinaton (ritual flags), used in the Great PaSta’ay celebrated every ten years, and the papotol (holy-sounding whips) used to expel the ta’ay spirits influencing the weather, treating them as semiotic devices that encode the relationship between the Saisiyat and the ta’ay. Cheng argues that rituals are not mere customs but organized performances of identity, designed to signal membership and continuity. His lexicon is poetic and precise—a tribute to the material culture of memory.

Liu returns with a comparative study of dwarf myths across Taiwan’s Indigenous groups. She categorizes the legends, traces their colonial and post-colonial interpretations, and offers a literature review that spans Qing dynasty records to contemporary fieldwork. Her work underscores a key point: the ta’ay are not an isolated phenomenon but part of a broader mythic ecology.

The final section, “Beyond Taiwan,” takes the reader on a mythic voyage. Dean Karalekas proposes the concept of a “Primordial Little People Tale-Type,” arguing that Austronesian voyagers carried the ta’ay myth across the Indo-Pacific as part of their cultural toolkit. These stories helped settlers make sense of new landscapes, unfamiliar peoples, and the existential dislocation of migration.

Gregory Forth, drawing from his work on Homo floresiensis in Indonesia, explores the possibility that legends of the lai ho’a among the Lio people may derive from real encounters with archaic hominins. He notes striking similarities between the Indonesian Lio hominoids and the ta’ay, suggesting a shared narrative tradition—or perhaps shared memories of vanished species.

Igor Sitnikov closes the volume with a comparative study of dwarf imagery in European folklore. He traces the evolution of gnomes, dwarves, and other short-statured figures from Greek and Egyptian myths to Slavic epics, arguing that these beings often serve as liminal figures—guardians of thresholds, keepers of secrets, and symbols of resilience.

What sets this book apart is its inclusion of Indigenous fiction. Writers like Domas Ayang, Kereker Palakurulj, and Lulyang Nomin contribute short stories that dramatize encounters with Little People. These tales are not decorative—they are epistemic interventions, asserting Indigenous agency in the telling of history. The editors’ decision to include them reflects a commitment to decolonizing scholarship, allowing Indigenous voices to speak not just about myth but through it.

Taiwanese scholars and fiction writers are not passive subjects but active narrators. This counters the long-standing dominance of Western anthropologists, whose work—however rigorous—has often been filtered through orientalist lenses. The collaboration here is genuine, respectful, and politically aware. It reflects a growing sentiment in Taiwan: that Indigenous knowledge must be co-produced, not extracted.

“Seeking the Koko’ Ta’ay” is a cultural reckoning. It affirms that Taiwan’s and China’s history is plural, layered, and resistant to erasure. It challenges nationalist myths and the use of archeology as propaganda in Xi Jinping’s China, honors Indigenous memory, and models a form of scholarship that is both rigorous and empathetic.

For readers who crave depth with flair, this book offers both. It’s a reminder that the past is not dead—it’s dancing in the forests of Taiwan, wearing hip bells and whispering secrets to those who dare to listen.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.