An ancient gesture becomes a powerful signal that freedom of religion and human rights are in danger in South Korea.

by Massimo Introvigne

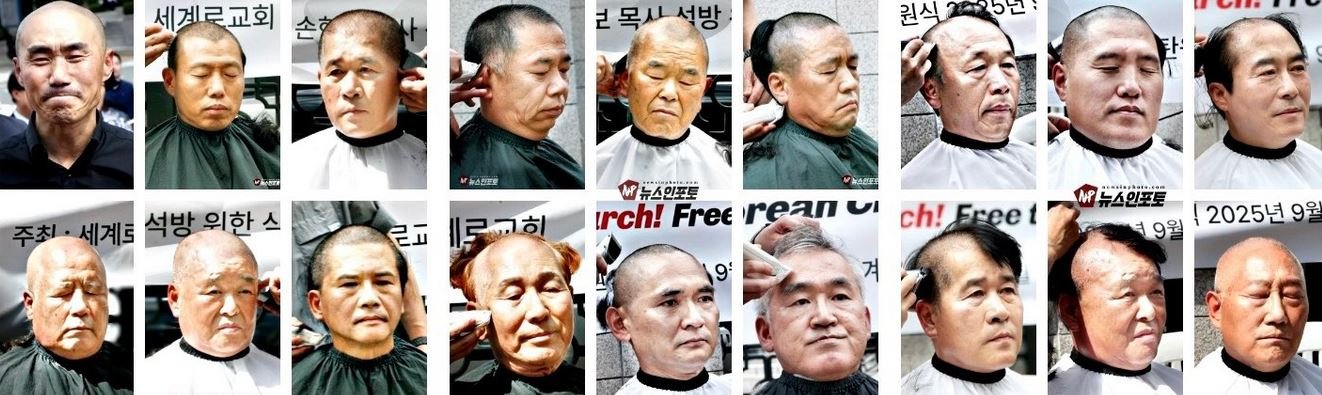

In a powerful act of solidarity and sorrow, dozens of members of Segero Church in Busan have shaved their heads to protest the continued detention of their beloved pastor, Son Hyun-bo. When the court denied the habeas corpus petition for Pastor Son, eighteen associate pastors and elders shaved their heads in protest. This month, another four young adults from Segero Church shaved their heads in an act of protest and appeal.

This ancient Korean gesture—once reserved for monks and mourners—has evolved into a modern symbol of resistance against what many perceive as a grave injustice.

The tradition of head shaving in Korea carries deep emotional and cultural weight. Historically, it signified grief, repentance, or spiritual devotion. In contemporary times, it has evolved into a form of political protest—an embodied cry that words alone cannot express. When Segero congregants gathered to shave their heads, they were making a powerful statement and mourning the erosion of religious liberty in their country.

Pastor Son’s story, as reported by “Bitter Winter,” reads like a tragic epic. A former Special Forces soldier turned preacher, he built Segero Church from a dying congregation into a thriving spiritual community. His sermons, focused on values rather than personalities, allegedly mentioned political candidates in passing—no more than two minutes in 30–40 minute homilies. Yet under South Korea’s Public Official Election Act, this was deemed illegal campaigning.

It is a crime for which, in the past, the clergy have been fined a few hundred dollars. Detention, let alone pre-trial detention, was unheard of. Yet, on September 8, 2025, Pastor Son was arrested. Detention was confirmed on September 24. The court cited “risk of flight” and “destruction of evidence”—claims his son, Chance Son, called ludicrous. “My father’s sermons are online. He’s lived in Segero Church for thirty years,” Chance said.

The emotional toll is mounting. On October 4, Chance posted on X that his father had caught the flu in detention and was denied timely access to medication. “His voice is almost gone,” Chance wrote. “Please pray that his health doesn’t get worse.”

On October 28, as reported by Chance, “My father, Pastor Son, appeared in court wearing a prison uniform after being jailed for over 50 days. The prosecutor, despite being asked multiple times by the defense, failed to present even a single piece of evidence. Not ONE. The hearing ended in just 15 minutes, yet the judge postponed the next trial for another month.” Pre-trial detention is clearly used as a form of punishment, which is prohibited by United Nations rules.

This is not an isolated case. Mother Han, the revered leader of the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification, is also imprisoned. At 82, she has endured lengthy interrogation, repeating the same questions for hours and hours. The charges against her—alleged political influence and misuse of church resources—have been widely criticized as politically motivated.

The parallels between Pastor Son and Mother Han are striking: both are religious leaders targeted under vague political pretexts, both face harsh treatment despite frail health, and both inspire fierce loyalty from their communities. Their cases raise urgent questions about the state of democracy in South Korea. When spiritual leaders are jailed for preaching values, and elderly women are interrogated to exhaustion, the line between justice and persecution begins to blur.

“Historically in Korea, head-shaving has long been a solemn act of resistance,” said Chance Son, “a symbol of deep conviction and moral urgency, often used when words alone could not move hearts. We will continue to fight peacefully. It is time to take the offensive and raise our voices. The solidarity of the Segero Church congregation stands firm.”

The shaved heads of Segero Church members are a protest and a lament. A lament for a country that once prided itself on religious freedom. A lament for leaders who now suffer for their faith. And a call to action.

We join their cry: Free Pastor Son. Free Mother Han. Restore dignity, restore liberty, restore faith in justice.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.