The “anti-cosmic” Satanism of some Black and Death Metal bands hates everything and everybody. Suicide is a logical consequence.

by Massimo Introvigne*

*A paper presented at the Occult Convention IV, Parma, September 6, 2025.

Article 5 of 5. Read article 1, article 2, article 3, and article 4.

Jon Andreas Nödtveidt, the Swedish musician leading the Black/Death Metal band Dissection, died by suicide in 2006 in what many see as a ritual act connected to the esoteric teachings of the Misanthropic Luciferian Order (MLO), later renamed the Temple of the Black Light. His death provides a rare insight into the intersection of music, Satanism, and metaphysical rebellion.

Born in 1975, Nödtveidt established Dissection in 1989. The band quickly gained recognition for its Black and Death Metal blend, marked by dark atmospheres, intricate compositions, and occult themes. Albums like “The Somberlain” and “Storm of the Light’s Bane” became Metal classics.

In the mid-1990s, Nödtveidt and fellow musician Johan Norman joined the MLO, a Swedish esoteric order that promoted anti-cosmic Satanism—a radical reinterpretation of traditional Satanic and Gnostic ideas. The MLO rejected the created universe as a prison and aimed to return to primordial chaos through ritual and metaphysical transgression.

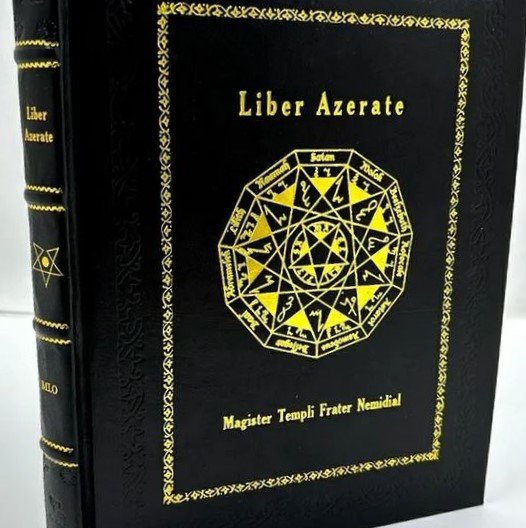

The MLO’s teachings were codified in the “Liber Azerate,” a grimoire by Frater Nemidial. The text describes eleven anti-cosmic gods opposing the ten Sefirot of Jewish Kabbalah. The practitioner’s goal is to destroy the illusion of the cosmos and awaken the Black Light of chaos.

The order taught that reality is a lie, imposed by a false creator god. True Satanists must reject morality, society, and even existence itself. Rituals included meditation, invocations, and symbolic acts of destruction.

In the Order, Satan was one of eleven gods and was on the verge of bringing chaos to our world. Nödtveidt called Dissection the “sonic propaganda unit” of MLO. Their Metal music style achieved remarkable success in the early 2000s, selling around 200,000 albums worldwide. This fame boosted MLO’s reputation despite remaining a small, secretive organization.

In 1997, Nödtveidt and “Vlad” murdered a randomly chosen gay man, Josef Ben Meddour, an Algerian immigrant, in what came to be known as the Keillers Park murder in Göteborg. This event was later depicted in the 2006 film “Keillers Park” directed by Susanna Edwards.

“Vlad,” or “Nemesis,” remains mysterious today. He comes from an Iranian immigrant family and was 20 years old at the time of the murder. His real name was Amir (Shain) Khoshnood-Sharis, and he may have been the founder or co-founder of the MLO, the same individual who signed the Order’s main books as “Frater Nemidial” and later “N.A.-A.218.” “Vlad,” as “Victor Draconi,” registered the trademark “Dissection” with the Swedish Patent Office in 2005.

Nödtveidt and Vlad, whose homes contained altars and paraphernalia of the Misanthropic Luciferian Order, admitted they planned to sacrifice Ben Meddour to Satan. They also paid homage to Norwegian Black Metal musician Bård Eithun, who had committed a similar crime against a gay man in Norway. Nödtveidt and Vlad were sentenced to ten years but were released in 2004, and Dissection resumed its musical activities.

Nödtveidt’s final album, “Reinkaos” (2006), was co-written with Nemidial and based on the “Liber Azerate.” Its lyrics reflect the order’s metaphysics, invoking chaos, liberation, and anti-cosmic warfare.

In August 2006, Nödtveidt was found dead in his Stockholm apartment, surrounded by candles, esoteric texts, and a loaded pistol. As anticipated in his songs, he had completed his spiritual journey and chose to “exit” the material world following MLO teachings.

His death was planned rather than impulsive. Friends and bandmates noted that he prepared for it, viewing it as a rite of passage. Though he did not leave a suicide note, he expressed contentment with his life and spiritual journey.

The musician was quoted in the Norwegian fanzine “Slayer” as stating that “the Satanist decides over his own life and death and prefers to go with a smile on his lips when he has reached his peak in life, after accomplishing everything and aiming to transcend earthly existence.” Just before his death, he also told another fanzine, “Evilution,” that “Satan represents something much greater than this world, this universe, or the creator of this universe. It is a force that constantly opposes creation and dismantles it until everything reverts to its primal chaos.”

Nödtveidt’s suicide was a metaphysical act—a rejection of cosmic illusion and an embrace of primal chaos. It was presented not as despair but as liberation. Nödtveidt was successful, articulate, and firmly committed to his beliefs. His death shows how esoteric belief systems can sanctify self-destruction, turning it into a spiritual ritual.

It also shows how subcultural aesthetics—Black and Death Metal, Satanism, and anti-cosmism—influence existential choices. The MLO’s teachings, while extreme, offer a clear framework for viewing death as a form of transcendence.

Ritual suicide is a rare but meaningful phenomenon. It accounts for a small part of global suicides, yet its symbolic significance far outweighs its frequency. When suicide is viewed as a religious or esoteric act, it questions our assumptions about agency, morality, and belief.

Across the case studies we’ve examined, several themes emerge:

- Transcendence: Suicide is often interpreted as a passage to a higher realm—whether paradise, liberation, or cosmic unity.

- Protest: Acts like self-immolation and revolutionary suicide express resistance against perceived injustice or oppression.

- Purification: Practices like Sallekhana and Sati frame death as a means of spiritual cleansing or fulfillment of duty.

- Apocalypse: Movements like the Ugandan MRTCG and the Solar Temple view suicide as a response to imminent eschatological crisis.

- Charisma and Authority: Leaders like Jim Jones and Di Mambro wielded immense influence, shaping followers’ perceptions of death and destiny.

- Initiation: Groups like Heaven’s Gate and the MLO reinterpret death through complex metaphysical systems, transforming suicide into initiation.

These cases remind us that suicide is not always a sign of despair. In religious and esoteric contexts, it can serve as an expression of faith, a rite of passage, or a means of making meaning. As scholars, our role is to understand rather than judge the beliefs and situations that lead people to view suicide as sacred.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.