Balla created memorable Futurist-Theosophical icons before leaving Futurism, becoming a “Fascist realist,” and returning to abstract art in his late years.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 5 of 5. Read article 1, article 2, article 3, and article 4.

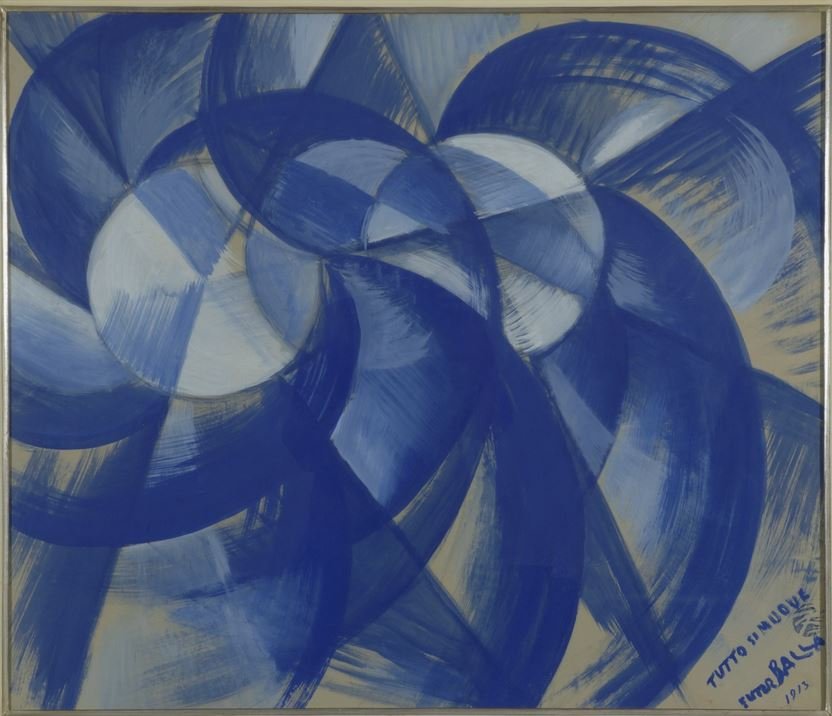

In 1913, Balla declared himself a mature Futurist and announced that his earlier works by the now-deceased painter Balla would be auctioned and dispersed. However, cooler heads prevailed, and Mayor Nathan, alerted by the painter’s wife, canceled the auction, saving most of the old paintings for the family. Balla’s reputation as a Futurist was reinforced through paintings highlighting speed and the movement’s central themes, often portrayed as a vortex, such as “Tutto si muove” (Everything Moves, 1913), a notably Theosophical image.

On November 7, 1914, Balla observed a partial solar eclipse caused by Mercury passing before the sun. He created several paintings titled “Mercurio passa davanti al sole” (Planet Mercury Passing in Front of the Sun).

Balla’s interpretation of the eclipse went beyond astronomy. He was familiar with French astronomer Camille Flammarion (1842–1925) works, who studied the occult meanings of celestial events. Flammarion was a prominent Theosophist and honorary Vice President of the international Theosophical Society from 1881 to 1888. Guido Valeriano Callegari (1876–1954), a pre–Columbian American art specialist before World War II, examined Flammarion’s ideas on Spiritualist séances and communication with the dead in his 1910 book “Flammarion.” That same year, Callegari married Amelia Raffaella Boccioni (1876–1964), sister of Boccioni.

Ginna first met Balla sometime after 1911, when the Ravenna-born artist visited Rome. During this trip, Ginna met and eventually married the Futurist poetess Maria Crisi (1892–1953), who attended the Rome Theosophical Society meetings. Ginna’s involvement with the Theosophical Society was officially recorded in the international registers in Adyar on February 19, 1913. In 1915, Balla and Depero authored the manifesto “Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe.” In Rome, he was recognized as the leader of a genuine Futurist circle where young artists gathered to learn about the movement’s spirit and aesthetic principles. Among them were Ginna, Benedetta Cappa (1897–1977)—whom Balla introduced to her future husband, Marinetti—her close friend Růžena Zátková (1885–1923), and a very young Julius Evola (1898–1974).

Evola, later mostly well-known as a right-wing esoteric political philosopher, was initially a painter associated briefly with Balla and the Futurists. During his studies with Balla, he also engaged with the Independent Theosophical League. Ginna remembered that he, Evola, and Balla discussed Blavatsky, Besant, and Steiner in the older painter’s studio while Boccioni was alive—i.e., before August 17, 1916. This shows that when Evola attended General Ballatore’s Theosophical meetings, Balla was already surrounded by friends and students passionate about Theosophy.

Flavia Matitti details Ballatore’s Theosophical career, while Fabio Benzi analyzed his writings in his 2007 book on Balla. Before helping establish the Rome Theosophical Association in 1897, Ballatore’s activities were less well-known. My research in Italian libraries reveals that he also authored works on military subjects, highlighting the need for soldiers to uphold high moral standards.

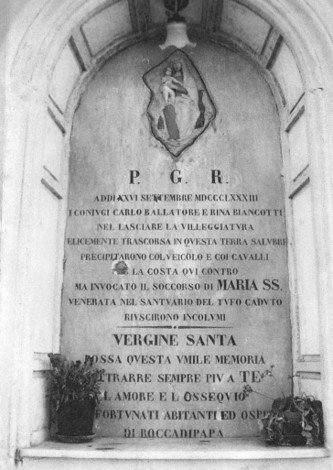

A notable artifact is a commemorative stone in a small Catholic shrine in Rocca di Papa, Rome, which I discovered by chance. The inscription recounts a miracle on September 26, 1883: Carlo Ballatore and his wife Rina Biancotti nearly fell into a gorge with their carriage and horses while leaving the village after their holidays. At that moment, they experienced a miracle of the Holy Virgin of Tufo, depicted in an image kept in Rocca di Papa, who miraculously intervened to save them.

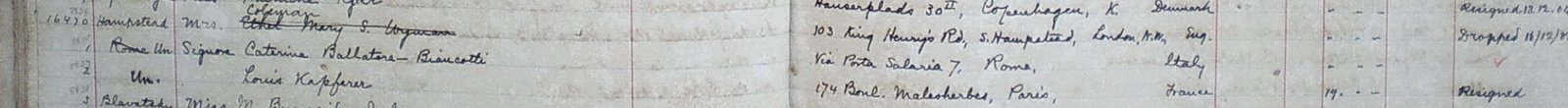

The shrine restorers and recorders of the event were unaware of Ballatore’s later links to Theosophy. Still, the wife’s name confirms he was the same military officer whose lectures on Theosophy Balla later attended. This incident highlights the Ballatore couple’s interest in the supernatural, as Rina later became a Theosophical lecturer and a member of the Adyar Theosophical Society (recorded from January 18, 1899). However, the path from Catholicism to Theosophy for them remains unclear.

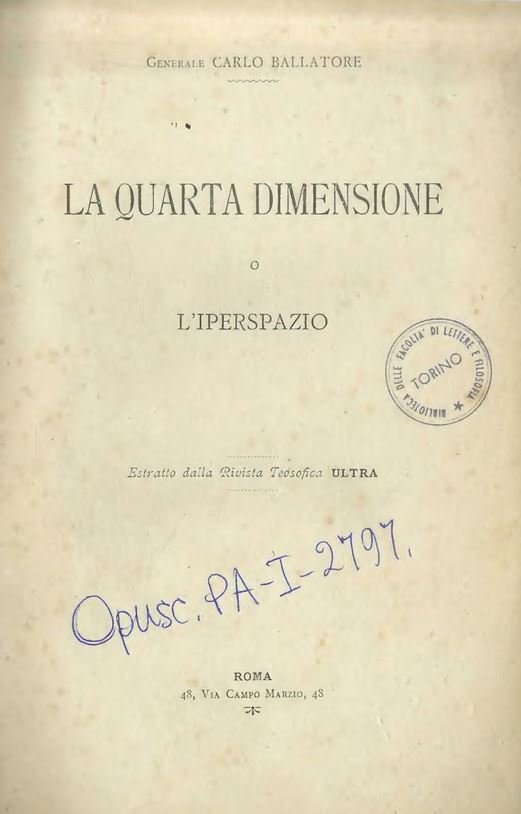

Benzi highlights an unpublished 1904 lecture by Ballatore at the Theosophical Society of Rome, which he later revisited with some additions in 1920—likely at the Independent Theosophical League. In this talk, Ballatore discussed the fourth dimension and the theories of Charles Howard Hinton (1853–1907), whose significance for international Theosophy and contemporary art has been thoroughly analyzed by American art historian Linda Dalrymple Henderson. He revisited these ideas in an article in “Ultra,” later published as a booklet titled “La quarta dimensione o l’iperspazio” (The Fourth Dimension, or The Hyperspace, 1908). Ballatore described how beings with only one or two dimensions would perceive the world.

Although he did not mention Edwin A. Abbott’s (1838–1926) 1884 novel “Flatland,” which shares a similar concept, Hinton influenced both Abbott and Ballatore. The Italian Theosophist explained that, as three–dimensional beings, we would appear to bi-dimensional entities in Spiritualist séances as “ghosts.” He argued that this is not mere “idle chatter,” but a plausible explanation of how spirits, residing in the fourth dimension, manifest to us in three dimensions. He also discussed how non–Euclidean geometries explore the fourth dimension, highlighting Hinton’s “tesseract” as a classic example of a “fourth dimension figure,” a topic Henderson has shown to be highly relevant for modern art.

Ballatore, who founded Rome’s first Theosophical Lodge before joining the Independent League, published a book in 1909 based on a 1907 article in “Ultra” about “universal and human” radioactivity. This topic was of great interest to Futurists. He described that occultists perceive things beyond our senses and called them “painters of the invisible,” who offer valuable models of the astral world, akin to artworks created intuitively with unseen assistance.

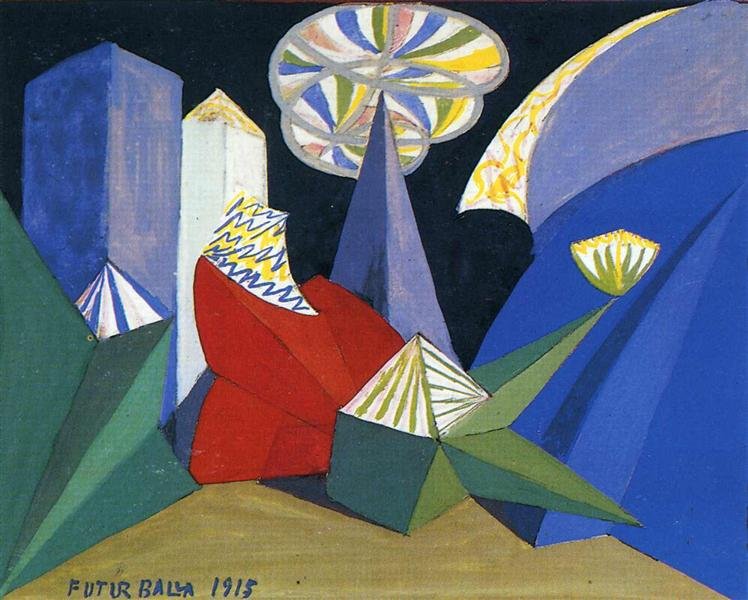

Ballatore also considered how to represent a fourth spatial dimension, mentioning vibrations as field lines or lines of force and “elastic” spheres that can interpenetrate. He believed these ideas closely aligned with Balla’s concepts, making a coincidence unlikely. Balla explored these themes in his mixed–media assemblages called “Complessi plastici” (Sculptural Aggregations, 1914–1915), of which only photographs remain, and possibly in “Il pugno di Boccioni” (Boccioni’s Fist, 1915). The idea of the fourth dimension also appeared in stage designs commissioned by Russian ballet impresario Sergei Diaghilev (1872–1929) for Igor Stravinsky’s (1882–1971) “Feu d’artifice” (Firework) at Rome’s Teatro Costanzi.

Elica Balla stated that Ballatore influenced his father to attend Spiritualist séances. This influence is visible in “Verso la notte” (1918), which features an ectoplasm and a spirit, and possibly in the 1920 self-portrait “Autostato d’animo,” where the artist may have intended to depict his astral form. In the early 1920s, Balla produced several important works that reflect Theosophical themes: “Sorge l’idea” (1920), “Scienza contro oscurantismo” (1920), and “Pessimismo e ottimismo” (1923), with multiple versions of some pieces.

This artwork consists of abstract paintings embodying Masonic ideals from the Nathan period, which Balla never completely abandoned. The essence arises from a formless chaos of ignorance; the light of science combats the dark red flames of obscurantism; a blue Optimism confronts a black Pessimism, depicted as a medieval knight. The painting may also reference images from “Utriusque cosmi” (History of Both Worlds, 1617) by the British Paracelsian physician Robert Fludd (1574–1637), as well as from Leadbeater’s “Man Visible and Invisible” and “Philosophia sacra.”

Balla’s use of shapes and colors embodies Theosophy while also narrating the rise of the Third Rome, which overcame the corrupt Second Rome ruled by clerics. When he created the tapestry “Genio futurista” (1925) for the Exposition Internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes (28 April–30 November 1925), he effectively integrated both Theosophical imagery and diverse interpretations of Third Rome mythology, offering a clear overview of his artistic concept.

Meanwhile, following the example of many (but not all) Futurists, Balla’s political views diverged markedly from Nathan’s. He saw Fascism as the strongest chance to realize the Third Rome, expressed in Mussolini’s speech on Capitoline Hill on 31 December 1925. Balla even envisioned a large fresco titled “Apoteosi fascista” (Apotheosis of Fascism). However, he only completed part of it, called “Le mani del popolo italiano” (The Hands of the Italian People, 1926).

That year, he also began work on “Marcia su Roma” (The March on Rome, 1932–1935), celebrating the 1922 Fascist coup. Additionally, he signed the third edition of “Manifesto dell’aeropittura” (Manifesto of Aeropainting, 1931), which Benzi views as an example of Balla’s “esoteric and Theosophical” influence, as the artists believed that flying could evoke a spiritual experience.

He was moving away from Futurism, with a marked break happening after Marinetti published the “Manifesto dell’arte sacra” in 1931. In this document, Marinetti suggested using Futurist talents, including aeropainters, to revitalize Catholic arts and churches. Although Balla was noted as an artist capable of depicting “the bliss of Paradise” in sacred art, he, a longtime friend of Mayor Nathan, was not interested in producing Catholic art, whether in a Futurist style or not.

The 1931 manifesto was not simply opportunistic. Other Futurists like Fillìa (Luigi Colombo, 1904–1936) and Gerardo Dottori (1884–1977), a student of Balla, produced significant religious artworks with Christian themes. Balla, who supported Freemasonry—specifically the Italian Grand Orient, which was essentially anti-Catholic—later severed his connections with Futurism. When the Fascists denounced Futurism and the avant-garde as “degenerate art” around 1937–1938, Balla claimed he was not involved with the movement.

Balla may have genuinely believed in Fascism at one time, which caused his ostracism and marginalization after World War II. Nevertheless, Fascists typically did not hold him in high esteem. Mussolini sympathized with him, but the regime never strongly supported Balla’s projects. Similarly, the progressive Italian art scene of the late 1940s and 1950s struggled to understand his shift back to figurative art from the 1930s to 1950s.

After the War, Italian abstract painters like Piero Dorazio (1927–2005), Carla Accardi (1924–2014), and Ettore Colla (1896–1968) rediscovered Balla, focusing on his Futurist abstract works rather than his post-war flowers and portraits. In response, Balla created some “neo-Futurist” pieces that sold more successfully. The circle of abstract artists he associated with was not connected to Theosophy, and there is no evidence that Balla maintained contact with the Italian Theosophical community during its post-war revival. Finally, despite his controversial ties to Fascism, Balla was ultimately recognized as one of Italy’s most significant twentieth-century artists.

Balla approached Theosophy with practical intent, not just as a theoretical pursuit. Unlike Lawren Harris (1885–1970) or Piet Mondrian (1872–1944), he did not focus on defining what makes art “Theosophical.” Despite his varied connections to these areas, his primary interest was the arts rather than spirituality or politics. In Italy, a nation troubled by cultural and religious conflicts, he deliberately kept his distance from a society controlled by the Catholic Church. Instead, Balla found his spiritual roots within a counter–hegemonic scene where Socialism, Neopaganism, Freemasonry, and Theosophy mingled and collaborated to support the idea of a “Third Rome” opposing Catholic hegemony.

Though Balla never wrote about Theosophy, Theosophical ideas in their many forms influenced him and inspired his art, which numerous historians have recognized over the years.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.