A fascinating work of sociology raises questions on Maoism, Maoists in the West, charisma, and submission.

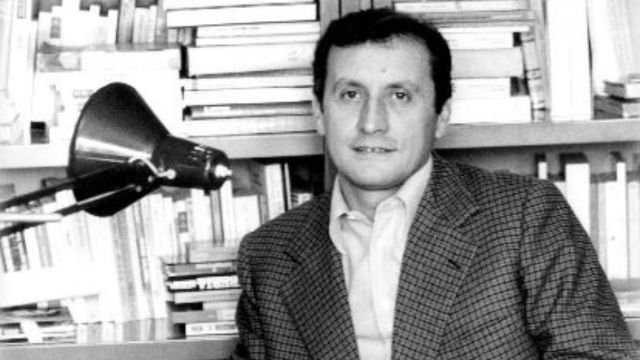

by Massimo Introvigne

Several years ago, I had a conversation with an interesting Italian politician called Aldo Brandirali. Although I had never met him before, I had come across his followers when I was in college. One among several Maoist movements active in Italian universities in the 1970s, they were an extraordinary group to observe for a young sociologist in the making. Their unique feature was the extreme cult of personality they tributed not only to Chairman Mao but to Brandirali himself. His portraits were ubiquitous in the group and its devotees could be found in the entrance hall of my university chanting “We follow Comrade Brandirali” and “Stalin, Mao, Brandirali!” I learned, already at that time, that some of them lived communally with Brandirali and that he celebrated their (not legally valid) marriages in the name of Chairman Mao—and of himself.

Brandirali later left his own Maoist group (which continued for a few years without him) and converted to Roman Catholicism after he met Father Luigi Giussani, the founder of the movement Comunione e Liberazione. As he told me, he had finally realized he was not himself a master but he needed one: Jesus, and at another level Father Giussani. Eventually, Brandirali also changed spectacularly his political ideas as he went from Mao to a totally different charismatic leader, Silvio Berlusconi, for whose party he became an influential member of Milan’s city administration in the 21st century.

Apart from his second and surprising Catholic and right-wing incarnation, I believed that Brandirali’s micro-group, functioning as it was like a Maoist new religious movement, was unique, at least in continental Europe (I was aware of the notorious Workers’ Institute of Marxism–Leninism–Mao Zedong Thought led by Aravindan Balakrishnan in London).

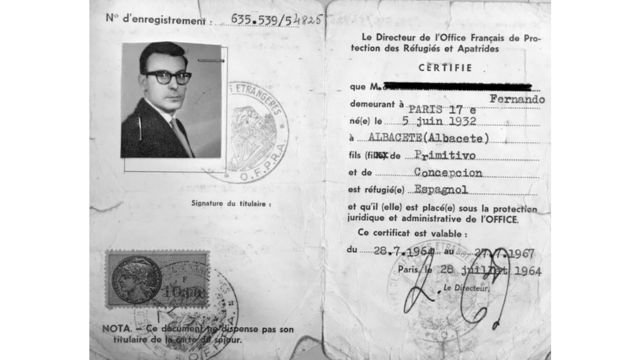

It turns out I was wrong. A recent fascinating book by French sociologist Julie Pagis, “Le prophète rouge. Enquête sur la révolution, le charisme et la domination” (Paris: La Découverte, 2024) describes a group very similar to Brandirali’s Italian Maoists and operating in the same decade, the 1970s, in an ex-convent in Clichy, in the banlieue of Paris. Its founder was a Spanish laborer called Fernando Fernandez (Pagis does not supply his last name but a review in “Le Monde” did). When in 1981 he decided to close the group, which had been formed in 1971, Fernando did not convert to Catholicism nor to the political right like Brandirali. He disappeared into comparative obscurity in Spain, where he became a shipowner, developed alcohol problems, had a serious car accident at the end of the 1980s, and died of cancer in 2008 at age 76. All these details were unknown to his former French followers and even to his estranged daughter, and were pieced together through Pagis’ painstaking research.

It does not appear that Fernando was ever able to self-criticize himself and the cult of his personality he had imposed on his followers as Brandirali did. Otherwise, there are obvious similarities between the two groups. Both tried a Maoist experiment in communal living, both told their intellectual members that, in a replica of the Cultural Revolution, they should become “embedded” with the people, finding employment as factory workers, and in both cases the leader exerted a strong control on the group.

The case of Fernando appears indeed extreme, and Pagis (who comes herself from the extreme left) is right in insisting it should not be taken as representative of all Maoist groups in the West. That it was a Maoist group is, however, without doubt, and a radical one: at one stage, members were counseled to stop reading even Marx and Lenin—Mao and Chinese propaganda magazines were enough.

The leader controlled the lives, the sexuality, the children of the members. He justified with ideological pretexts his own sexual escapades and mistreatment of his female partners. And he created, along the style of the Cultural Revolution in China, a pervasive and paranoid system of self-criticism and of identification of members of the group as “class enemies” to be punished. The latter were persuaded themselves that they suffered of the “illness” of “revisionism” and needed Fernando to be “cured.” In the end, however, the pressure was simply too much and the group collapsed.

The interpretive effort by Pagis in a country like France, where the fight against “cults” (sectes) is part of the official discourse, ran the risk of using the easy stereotype of the “cult” (la secte) and of a “guru” (gourou) using “brainwashing” to maintain his “victims” under “control” (emprise). Refreshingly, Pagis explicitly rejects the “reductive, miserabilistic interpretations of the emprise of a gourou.” She wants to “get away from psychologizing and victimizing analyses of ‘manipulation,’ which is often understood as the intentional action of a Machiavellian individual against victims who have been deprived of the power to act, when they are not presented as ‘psychologically weak.’”.

Revisiting Max Weber’s theory of charisma, Pagis believes that those who decide to follow a prophet, and are thus “charismatized,” participate in the construction of the charisma not less than the leaders themselves. This, however, leaves Pagis with the question of how Fernando, a simple worker, could enter into a charismatic relationship where he dominated followers whose social and cultural capital was higher than his own. In fact, Pagis himself admits she had fallen for a while under the spell of Fernando, whom she never met personally, during her research, before becoming indignant at how he mistreated his followers and particularly the women. To complete her book, Pagis needed herself therapy with a psychologist.

Fernando exhibited two types of credentials, his alleged opposition to the Franco regime in Spain and the fact that he had lived for a short time in China and worked for the Communist Party there translating Mao’s writings. Pagis’ detective work revealed that the first credentials were probably false and the second real but less important than Fernando claimed. Although she didn’t find conclusive evidence, she believes that the fact that Fernando could have moved between China, France, Spain, Portugal, and even Cambodia with comparative ease, sometimes with the benevolence of high bureaucrats, suggests that he might have been working for the intelligence services, of which country remains unclear.

There was much that was simply false in Fernando’s autobiographic stories. However, building and passing off persuasively apocryphal stories about themselves, Pagis concludes, is part of the charisma of the prophets. It is a charisma that requires “charismatized” followers to be effectively built.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.