Democracy, as everywhere, came gradually. So did religious liberty, which had been severely limited during the Martial Law period.

by Tsai Cheng-An

Article 2 of 7.

Read article 1.

Taiwan’s democratic development has been divided into three stages: the authoritarian rule before the lifting of Martial Law in 1987, the post-authoritarian rule from 1988 to 2016, and the period inaugurated by the third-party rotation in 2016. International scholars generally believe that democracy is a learning process, and a country can only be called democratic after it has experienced for three times a comprehensive rotation of the political parties in power.

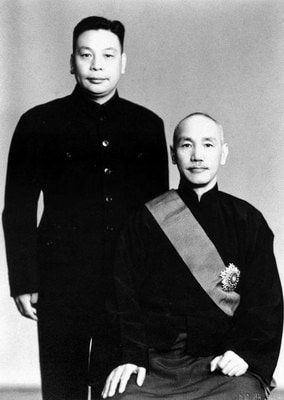

During the authoritarian regime from 1945 to 1987, there was no concept of human rights. Judicial control and legal delegation served the administrative power and the regime, allowing for complete administrative discrimination. Under the leadership of Chiang Kai-Shek (1887–1975) and his son Chiang Ching-Kuo (1910–1988), their party, the Kuomintang (KMT), ruled under the Martial Law of the Republic of China (Taiwan). This authoritarian government controlled the people and all groups through the Martial Law and the “Special Regulations on Mobilization and Rebellion.” Authoritarian governments relied on their powerful political parties, governments, military police, secret services, judiciary, tax bureaucrats, used as one whip force against any group, including religions, deemed to harm the “national security.” They were ruthlessly suppressed and persecuted.

A martial law gives the government enormous powers to eliminate any form of social dissent. In February 1947, a year before the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was issued, the KMT government repressed protests across Taiwan, in what was known as the “228 Incident.” The government issued the “Report on the Rebellious People,” searched the country, and wiped out the rebels. Tens of thousands died. This ushered in another period of national terror. The peak of the period of national terror came in 1955 and was known as the “White Terror.” The KMT government imprisoned, tortured, and executed thousands of people over a period of decades.

Before Martial Law ended in 1987, the political atmosphere of the country obviously limited human rights, and extended the oppression to the social, cultural, and religious fields by suppressing independent movements. The state indoctrinated the citizens and manipulated the mass media ideologically. All media in Taiwan were under the shackles of a series of strict legal norms and policy control. The Kuomintang government during this period allowed only limited space for freedom of thought, and forbade all promotion of Marxism-Leninism or socialism that might destabilize the legitimacy of its regime.

During the period of Martial Law, the ruling party and government forces went deeply into religion and imposed strict restrictions on religious freedom. The freedom of religious belief theoretically guaranteed by the Constitution was denied in practice. If religious groups were perceived as having different political positions from the government, they were repressed. For example, Yiguandao, the New Testament Church (Mount Zion), and even the large Presbyterian Church in Taiwan, all suffered political persecution.

The New Testament Church is a Pentecostal movement founded by Christian Hong Kong movie star Mui Yee (1923–1966). After her death, Elijah Hong became the new leader, and established new headquarters at Mount Zion, near Kaohsiung, in Taiwan. What was called the “Mount Zion Incident” began in March 1974, when the authoritarian government of Taiwan arbitrarily declared the legal household registration certificates of New Testament Church members who lived communally there invalid and set up checkpoints at the entrance of the area. The military and the police jointly raided the community and arrested several members.

On April 1, 1980, the Supreme Administrative Court ruled that the household registration certificates were valid. In the meantime, however, members who lived in Mount Zion had been dispersed, including women and children, the church sanctuary and all the houses of the devotees had been demolished, and the property the members had left there had been looted or confiscated.

In 1985, the military and police again raided the communities of the New Testament Church that had been reorganized across Taiwan. In several cases, devotees were beaten, leading to cases of kidney bleeding, deafness, and even death from severe injuries. In the following years, the authoritarian government continued to display unprecedented violence against the believers. Only in 1987 was the New Testament Church allowed to return to Mount Zion, after the U.S. government had expressed its concern to Taiwan’s authorities.

Yiguandao is a non-Christian salvationist new religion, which was banned in Mainland China in the 1950s. As a result, many members came to Taiwan hoping they would be allowed to freely practice their religion there. However, nationalist politicians were also suspicious of the fiercely independent salvationist new religion. In Taiwan, Yiguandao was labeled a “xie jiao” (“organization spreading heterodox teachings,” sometimes translated as “evil cult”) and banned from missionary practice for thirty years, with several leaders arrested.

A Western scholar of Yiguandao, Edward Irons, reports how during the Martial Law period leaders of Yiguandao were invited by the police to “drink a tea,” after which they “disappeared.” Yiguandao was legalized in Taiwan only in 1987, just before the lifting of the Martial Law.

Tsai Cheng-An received his Ph.D. in Technology Management from National Chengchi University and his MS in Industrial Engineering from National Tsinghua University in Taiwan. He teaches innovation management, business model analysis, and new business development strategies at Shih Chien University, Taipei, Taiwan. Prior to his academic career, he had 18 years of practical experience in the industry, and his research interests are in decision making, business model innovation, and corporate entrepreneurship, as well as in the area of transitional justice and freedom of religion or belief. He has published in the International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviors & Research (SSCI), Technology Analysis and Strategic Management (SSCI), Logistics (SCIE), Management Review (TSSCI), Journal of Management (TSSCI), Sun Yat-sen Management Review (TSSCI), Journal of Science and Technology Management (TSSCI) and Forum for Industry and Management (TSSCI).