A new report documents a subtle tool of cultural genocide: erasing the village names referring to Uyghur culture and religion.

by Massimo Introvigne

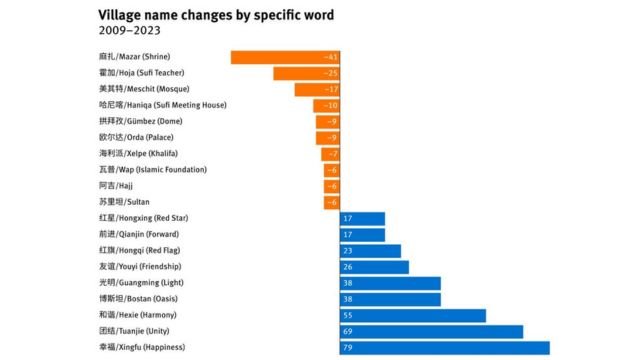

On June 18, Human Rights Watch (HRW) released a detailed report on villages whose names were changed by the Chinese authorities in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR), which its non-Han inhabitants prefer to call East Turkestan. HRW found that between 2009 and 2023, out of some 25,000 villages in Xinjiang, about 3,600 had their names changed. In some cases, the changes were deemed by HRW “mundane” and adopted for practical reasons. However, the human rights organization identified 630 cases where the village name change was aimed at erasing references to Uyghur religion, history, and culture.

These changes, HRW reports, fall into three categories. “Any mentions of religion, including Islamic terms, such as Hoja (霍加), a title for a Sufi religious teacher, and haniqa (哈尼喀), a type of Sufi religious building, have been removed, along with mentions of shamanism, such as baxshi (巴合希), a shaman.” Second, “Any mentions of Uyghur history, including the names of its kingdoms, republics, and local leaders prior to the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, and words such as orda (欧尔达), which means ‘palace,’ sultan (苏里坦), and beg (博克), which are political or honorific titles, have also been changed.” Third, “The authorities also removed terms in village names that denote Uyghur cultural practices, such as mazar (麻扎), shrine, and dutar (都塔尔), a two-stringed lute at the heart of Uyghur musical culture.”

Some examples: the village in Karakax County called Two-Stringed Lute (Dutar, 都塔尔), became Red Flag village (红旗村) in 2022. In Aksu Prefecture, Hoja Eriq (“Sufi Teacher’s Creek”) village (霍加艾日克村), became Willow village (柳树村) in 2018. Also in 2018, in Akto County, Kizilsu Kyrgyz Autonomous Prefecture, the village of Aq Meschit (“White Mosque,” 阿克美其特村) became Unity (团结村). Names of historical Muslim figures were eliminated as well. In Kashgar Prefecture, Qutpidin Mazar village (库普丁麻扎村), named after a shrine of the 13th-century Persian poet, Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi, became Rose Flower village (玫瑰花村), again in 2018.

HRW statistics show that 41 villages lost the name Mazar (shrine), 25 lost the name Hoja (religious teacher), and 11 the name Meschit (mosque). As opposite to this, 69 villages got a new name including Unity (referring to anti-separatist slogans), 23 were renamed Red Flag and 17 Red Star.

HRW should be applauded for having documented yet another tool of oppression and cultural genocide. Apart from the paradoxical practical consequences mentioned in the report—with villagers facing problems with the rigid and slow Chinese bureaucracy in adapting to the new names—, the CCP’s aim is to erase all traces of what makes Uyghur culture distinctive. It is just another way of depriving Uyghurs of their Uyghurness.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.