A long process made the “Way of the Ru” an ideology governing the bureaucracy, education, and the imperial rites. The label “official religion” may however be misleading.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 4 of 5. Read article 1, article 2, and article 3.

This is not a history of “Confucianism,” much less a systematic presentation of its doctrines, which extend to such diverse fields as morality, music, and politics. The much more limited purpose of this series is to discuss whether the tradition of the Ru commonly associated with the name of Confucius can be regarded as “religious” or, on the contrary, as “atheistic.”

So far, we have discussed the issue in general terms, something that may lead to overlook the fact that the Ru tradition evolved during at least 2,500 years and, as all traditions do, changed. “At least” because, as we have seen, Confucius claimed that he had not invented anything and had merely collected and restored previous wisdom. Ideas and rituals connected with the Ru, if not the word “Ru” itself, existed before Confucius.

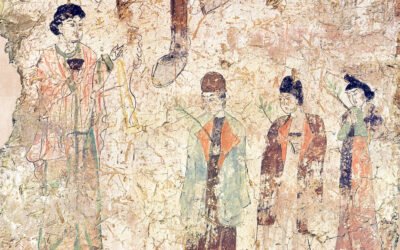

In Confucian temples, the sage is often depicted surrounded by four key disciples, Yan Hui (ca. 521–481 BCE), who died young, but is mentioned in the Analects as the master’s favorite, Mengzi (372–298 BCE), whose name was Latinized by the usual Jesuits as Mencius, Zengzi (505–435 BCE), and Zisi (483–402 BCE).

The “Great Learning” by Zengzi, the “Doctrine of the Mean” by Zisi, and the “Mengzi” by Mencius, together with the Analects, came to constitute the Four Books, or the Confucian canon. “Disciples,” here, does not mean that they were taught by Confucius personally, but that they belonged to a chain of transmission. Zengzi, a direct disciple of Confucius, taught Zisi, who happened to be Confucius’ grandson, and Zisi in turn was the teacher of Mencius.

Zengzi, Zisi, and Mencius had to teach during the troubled Warring States Period (476–221 BCE). Mencius, who centuries after his death came to be regarded as the “second sage” almost on equal footing with Confucius, was less successful during his lifetime. He preached against wars of aggression, and recommended to focus on cultivating “xin,” a word that means both “heart” and “mind” and is sometimes translated as “heart-mind” —or perhaps should not be translated at all.

Confucius believed that Tian, Heaven, was unknowable in itself but its designs could be understood by looking at human history. Mencius did not deny it, but he believed an even quicker way was to understand Heaven was through our own xin. Those who know xin know human nature, Mencius taught, and those who know human nature know Heaven. If this looks like introspection, it is because it was. Mencius spent much less time than Confucius discussing rites, which was another reason he was not popular with the kings of the Warring States Period, who saw rituals as a tool of government.

Because of the honors tributed to Mencius, many tend to forget today that the triumph of Confucianism as China’s official ideology, which looked improbable in the Warring States Period, yet started becoming a fact under Emperor Wu of the Han dynasty (156–87 BCE), happened not thanks to Mencius but against him. The version of Confucianism that Emperor Wu decided to patronized was that of Xunzi (ca. 310–238 BCE), who was born some ten years before Mencius’ death.

While Mencius regarded human nature as basically good, Xunzi saw it as a mixture of goodness and evil, with the evil at constant risk of prevailing. A quick look at the dates confirms that Xunzi was still teaching during the troubled Warring States Period, which somewhat explains his pessimism. To overcome evil in human nature, Xunzi taught, rituals are crucial, and there is nothing wrong in using them to consolidate the power of the rulers.

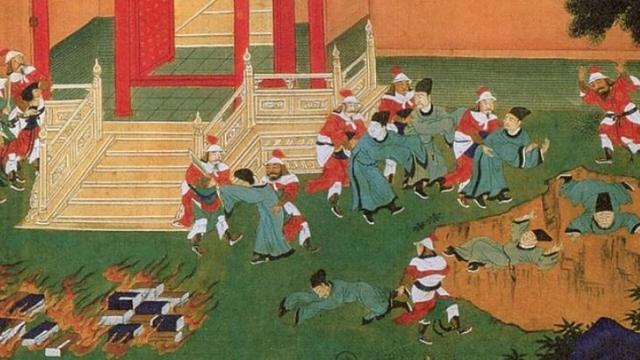

Xunzi had two controversial disciples called Han Feizi (ca. 280–233 BCE) and Li Si (280–208 BCE). They went much further in emphasizing the primacy of the rulers, and became notorious as advisers of Emperor Qin Shi Huang (259–210 BCE), the founder of the Qin dynasty. Having unified the country after the Warring States Period, Qin proclaimed himself the First Emperor of China. He was also a tyrant, who believed the scholars may conspire to overthrow him.

Allegedly, he ordered the books of the Ru tradition burned and 460 Ru scholars buried alive, although whether he really killed human beings rather than destroying books only is disputed by modern scholars. Reportedly, Han and Li supported the emperor’s infamous actions, which for a while reflected negatively also on the fame of their master Xunzi.

However, the short-lived Qin dynasty collapsed four years after the death of his megalomaniac founder. The Han came, and they were there to stay for four centuries, from 202 BCE to 220 CE (with a short Xin dynasty intermission from 9 to 23 AD). The Ru did not immediately recover from the book-burning crisis, and they had to compete with other schools. Traditionally, the story told is that Dong Zhongshu (179–104 BCE), a Ru who interpreted his tradition within the framework of the universal interplay of yin and yang, prevailed upon Emperor Wu and persuaded him to create the system of hiring Ru to teach the Classics.

Appointees to official positions were selected based on their knowledge of the Classics, which later evolved into the complicated system of exams. In a word, Wu is credited with having converted Confucianism into a “state religion,” something modern scholars see as an exaggeration. Wu only started a process that took centuries to consolidate and, although Dong was a renowned thinker, his role as advisor of the emperor was perhaps exaggerated by later Confucians as well.

Slowly, however, the position of “Confucianism” (remember, the name did not yet exist) was consolidated and, while having to coexist with Buddhism and Taoism, it came to dominate the court rituals and the system of education and governmental appointments. It was the result of a long and not linear process, with Ru Learning (Ruxue), the study of the Classics, and the Classic-based exams becoming the cornerstone of the Imperial system around 1000 CE.

They continued in this role for more than 900 years until the fall of the Empire in 1911. The orthodox interpretation of Ru came to be recognized as the one given by Zhu Xi (1130–1200), the most influential Medieval philosopher of China. He is also very important for the question of “religious” Confucianism.

By Zhu’s time, “Confucian” thinkers had come to agree that the stuff of the universe was something called Qi. Zhu explained that Qi changed and consolidated into the forms of non-living and living beings under the impulse of “Principle” (Li). Zhu maintained that Li is precedent to Qi, which would seem to place him closer to Buddhist and Taoist ideas about a universal, although impersonal, source of all beings.

However, Zhu explained that Li is not really separated from Qi, but exists “in” Qi only. Some English-speaking scholars have translated Zhu’s “Principle” as “Supreme Ultimate.” However, again, the Supreme Ultimate does not really exist independently and separately from its manifestations. If it is a divine principle, it is an eminently immanent one.

In the early modern era, as the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), which was not always protective of the Ru as a class of scholars but maintained the main structure of official rites and exams, ruled for almost three centuries, another great teacher emerged, Wang Yangming (1472–1529). He believed in the Principle, but regarded attempts by Zhu to understand it starting from the natural world as futile. There is only one locus where the Principle can be apprehended, Zhang said, our own xin (heart-mind).

In the 17th century, the Ming were replaced by a foreign dynasty, the Manchu Qing (1644–1912). They needed to control an enormous empire where they were part of an ethnic minority. They reinforced the Confucian system of administering the state and the rites, but discouraged wild philosophical speculation. They favored a return to Xunzi’s ideas about a way of the Ru that kept the evil trends of human nature in control and supported the rulers through the rites. The leading Qing Confucian was Dai Zhen (1723–1777), who taught that Principle existed, but was just the form making things what they are. There was no Li (Principle) independent of Qi.

With the Qing, the Way of the Ru—which in the last years of the dynasty some finally started to call “Confucianism” (Kongjiao)—still remained at the core of education and bureaucracy, but it became somewhat dry and uninspiring. It had to face new forms of competition by Christianity and by a plethora of new religious movements. Some of them criticized Confucianism, others claimed to embody Confucius’ most genuine spirit.

Then, in 1912, the collapse of the Empire destroyed the system of the so-called official Confucianism. Some saw in this disaster the opportunity to reconstruct Confucianism in a totally different way, as a religion or “church” similar to other religions. We will examine their attempts in the next article of this series.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.