Alatau District Court refuses to declare the human rights activist a wanted fugitive.

by Dilnur Sultanov

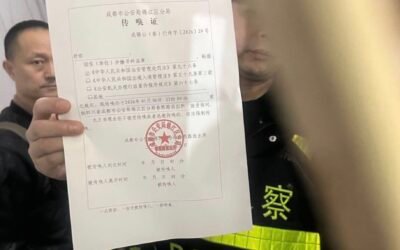

On December 20, judge D. Aikulov of Alatau District Court in Almaty rejected the request by the Alatau District Probation Department to declare Serikzhan Bilash a wanted fugitive. Against Bilash, who is currently abroad, China exerted heavy pressures on Kazakhstan because of the activist’s work in denouncing atrocities against ethnic Kazakhs in Xinjiang’s transformation through education camps, and his role in the preparation of a recent series of articles in Bitter Winter collecting voices of refugees who escaped from Xinjiang to East Kazakhstan.

But what was Bilash’s trial all about? It was largely a sideshow for the benefit of foreign observers, aimed at discrediting Bilash and his work on the camps in Xinjiang by falsely claiming that he was obliged to stay in Kazakhstan and went abroad illegally. The second goal was creating some confusion about the court cases involving Bilash, whose accounts and real estate were frozen, and all other property confiscated. The first case, in 2019, concerned inflammatory remarks and alleged “hate speech” against China Bilash used in his campaign about the Xinjiang camps. The government even registered him as a “terrorist” for this, although on August 16, 2019, the case was settled with a plea bargain.

Two more criminal cases were filed against Bilash in 2020 as part of the conflict between different branches of the human rights association Atajurt, two pro-government, pro-Chinese, and registered with the names Atajurt Zhastary (Atajurt Youth) and Atajurt Eriktileri (Atajurt Volunteers) and one, led by Bilash, called Atajurt Kazakh Human Rights, which was refused registration and denounced the Kazakh government’s attitude towards China.

Bilash is critical of the other branches, which have downplayed the presence of ethnic Kazakhs in the re-education camps in Xinjiang, and even denied that such camps (still) exist. It is important to note that these are not internal problems within an organization. Many Kazakhs see the two registered Atajurt organizations as mere attempts to deceive Western observers about the real situation of ethnic Kazakhs in Xinjiang.

The first case against Bilash was filed under the law punishing activities on behalf of unregistered or banned organizations. The second was filed at the request of Yerbol Dauletbek, the leader of the one of the pro-government “Atajurt” organizations, which wanted to take out from Bilash his YouTube channel also named “Atajurt.” It is clear that all this activity against Bilash has only one aim, to stop his criticism of China and the CCP, and his work on behalf of ethnic Kazakhs persecuted in Xinjiang.

Uses a pseudonym for security reasons.