Laws should always embody justice, or justice becomes what laws arbitrarily decide it to be. As the Tai Ji Men case shows all too well after 29 years, not all laws are just.

by Marco Respinti*

*Conclusions of the webinar “The Judiciary, Freedom of Religion or Belief, and the Tai Ji Men Case,” co-organized by CESNUR and Human Rights Without Frontiers on January 11, 2025, Taiwan’s Judicial Day.

We are at the beginning of a new year, and counting years by numbers prompts some considerations. 2025 marks the turn of the first quarter of the 21st century, which is also the first quarter of the new millennium in the calendar used in the West. The Western calendar is of course in use also beyond the boundaries of “the West” (whatever those may be), at least as a companion to other local and traditional calendars peculiar to different peoples and cultures. This is done to facilitate communication and exchanges of all nature.

Our first webinar on the Tai Ji Men case for the new year 2025 takes place on a very important date for the Republic of China (ROC) in Taiwan—home to many good things and also, unfortunately, to the sad Tai Ji Men case. This date is called Judicial Day and commemorates a central fact for the Republic of China and for the Taiwanese people, as well as for Taiwanese democracy and thus for democracy in the world.

Decades ago, January 11, 1943, marked the achievement of a full operative rule of law in the Republic of China (ROC), making it judicially independent from other powers. That was of course the ROC on the Mainland, but it continued also when, for dire political reasons, the ROC had to relocate itself on the island of Taiwan.

As we had the occasion to note in earlier webinars in this series, full judicial independence makes a country mature and sovereign. On January 11, 1943, the ROC was able to eliminate the exemptions from Chinese legal jurisdiction that, during the 19th and 20th centuries, came to be granted by force to citizens of certain Western countries.

I return to years and numbers. The beginning of the year 2025 reminds us that, as we underlined often during this series of webinars as well as in speeches, articles and books, the ordeal to which Tai Ji Men has been condemned for having committed no crimes (as all levels of the Taiwanese justice repeatedly established) has peaked the astonishing figure of 25 years. This hits the imagination even more when it is referred to as a quarter of a century—something this new year 2025 marks for the new century and the new millennium. This is quite a record for a group of citizens that has been proved innocent. However, the year 2025 relaunches that idea. It reminds us that in fact the Tai Ji Men case has lasted for “more” than 25 years of suffering. Tai Ji Men has now entered nothing less that its 29th year of sorrow, always without having committed any crime.

It is then quite apt to open our new season of advocacy for Tai Ji Men, in the name of freedom of religion, belief or conscience for everyone, in the year that marks this special number. The Judicial Day reminds to all that more than 80 years ago—exactly, 82—the ROC eliminated all discrepancies in law and all unequal treatment under the law, becoming a fully independent nation. Yet, despite that pivotal fact, after 82 years some citizens of the ROC, namely Tai Ji Men’s Shifu, or Grand Master, and dizi, or disciples, are treated unequally by ROC’s judicial system. They are subjected to legal consequences incompatible with their status as innocent people (as many courts of law ruled, including the Supreme Court) and unconceivable for a country where the rule of law is declared the pillar of democracy.

A few simple questions then remain. How can the ROC fully enjoy and celebrate its 82nd Judicial Day in face of this blatant injustice? How can the ROC fully enjoy and celebrate its Judicial Day after twenty-nine years of denying equal legal treatment to a group of its own pacific, law-abiding, and patriotic citizens? How can the ROC’s political and legal establishment tolerate this evident diminishment of its democratic status? How can the world pretend not to see this failure in international democracy?

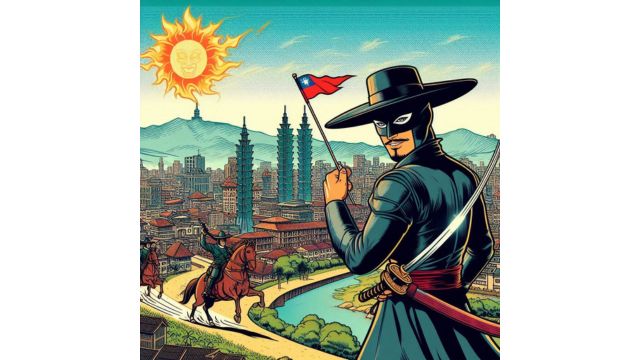

In search of an answer, literature comes to my aid. On the August 6, 1919, issue of the pulp magazine “All-Story Weekly,” American writer Johnston McCulley (1883‒1958) published the novel “The Curse of Capistrano” that marked the birth of a memorable fictional character, Zorro. This is a refined gentleman turned into a masked hero that champions the poor and the oppressed fighting villains in the old Spanish California. His nickname meaning in Spanish “The Fox,” he is astute and intelligent, brave and a great swordman, fascinating and elegant.

His stories made easily their way to the screen, immortalized in a famous 1920 film starring American actor Douglas Fairbanks (1883‒1939), “The Mark of Zorro,” as well as a TV series that was interpreted by American actor Guy Williams (1924-1989) and produced by Walt Disney, airing in 1957‒1959 (with additional special episodes in 1960‒1961). Zorro took then the shape also of comics and cartoons, the persona of Spanish actor Antonio Banderas in more recent movies, and the form of a brand-new TV series produced in Spain in 2024, with Spanish actor Miguel Bernardeau as the title character.

Famous Chilean American writer Isabel Allende created a fascinating new biography of the character in a 2005 novel, “El Zorro: comienza la leyenda,” or “Zorro: The Legend Begins.” One of the most intriguing aspects of Zorro is truly his origins, as well as his progeny. McCulley took inspiration from the novels by conservative, even reactionary Hungarian British author Baroness Emma Orczy (1865‒1947) who, in the early 20th century, created the Scarlet Pimpernel, or an English nobleman-turned-capped avenger. He managed to cross the British Channel to fight against the Jacobins in France during the French Revolution (1789‒1799). Now, the Scarlet Pimpernel was modelled on the Catholic protagonists that in real history rebelled against the Jacobins in Vendée, in North-Western France, between 1793‒1794 to be slaughtered in what has been called a genocide. Most probably the model used by Baroness Orczy was Henri du Vergier, Comte de la Rochejaquelein (1772–1794), who died at age 21 fighting as the commander-in-chief of the Catholic and Royal Army of Vendée.

But in turn this Zorro of Vendean origins has served as the model for another great fictional hero, Batman, or the millionaire who in the imaginary Gotham City turned into yet another dark knight for justice. It was created in the May 1939 issue of American magazine “Detective Comics” by American comic artists Milton “Bill” Finger (1914–1974) and Robert “Bob” Kane (1915–1998).

What is peculiar here is that the fight of these heroes, where history mingles with fiction, is always defensive and never offensive. They are normal men with no super-powers who try to avoid violence, using it only when it is strictly necessary and limiting damages. These fictional counterparts to real historic heroes also avoid killings, since the power of their authors can manage even that.

They apply true justice even when justice is betrayed by those who are supposed to uphold it. This basic idea surfaces in many of the adventures of Zorro. It goes like this: when laws do not serve justice, then justice has the right not to serve the laws. Of course, these stories are fictional, but in real life this translates as: laws should always embody justice, otherwise justice becomes what laws arbitrarily decide it to be. And, as the Tai Ji Men case shows all too well after 29 years, and in this special year 2025, laws can sometimes be unjust.

Marco Respinti is an Italian professional journalist, member of the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), author, translator, and lecturer. He has contributed and contributes to several journals and magazines both in print and online, both in Italy and abroad. Author of books and chapter in books, he has translated and/or edited works by, among others, Edmund Burke, Charles Dickens, T.S. Eliot, Russell Kirk, J.R.R. Tolkien, Régine Pernoud and Gustave Thibon. A Senior fellow at the Russell Kirk Center for Cultural Renewal (a non-partisan, non-profit U.S. educational organization based in Mecosta, Michigan), he is also a founding member as well as a member of the Advisory Council of the Center for European Renewal (a non-profit, non-partisan pan-European educational organization based in The Hague, The Netherlands). A member of the Advisory Council of the European Federation for Freedom of Belief, in December 2022, the Universal Peace Federation bestowed on him, among others, the title of Ambassador of Peace. From February 2018 to December 2022, he has been the Editor-in-Chief of International Family News. He serves as Director-in-Charge of the academic publication The Journal of CESNUR and Bitter Winter: A Magazine on Religious Liberty and Human Rights.