The British artist claimed that she did not paint anything. A spirit called J.P.F. did, using her as a mere tool.

by Massimo Introvigne

Among several painters who claimed their hands were guided by spirits, less known than such artistic superstars as Hilma af Klint (1862–1944) is Constance Ethel Le Rossignol (1873–1970). However, her unique style and career deserve more attention than she has usually received.

She was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in a family originally from Jersey, Channel Islands. Her parents were Alfred Le Rossignol (1840—1909) and his wife Jemima McLean (1842–1876).

They returned to England, where Ethel, who had lost her mother when she was only three years old, eventually received some formal artistic education. She served as a nurse between 1914–1919 in World War I and left an interesting correspondence with her brother Arthur Stanley Le Rossignol (1875–1943), documented with several photographs. The American University of Notre Dame acquired this material as part of their World War I collections, apparently not realizing that the nurse later became a painter of some distinction.

In England, Constance Ethel married in 1930 Arthur Beresford Riley (1868–1934), but he died prematurely only four years after the marriage. She never married again.

As many other Britons who experienced the tragedies of the War, Ethel turned to Spiritualism and became herself a medium. In 1920, she started channeling a spirit simply known as J.P.F. and producing paintings for which she claimed no credit, insisting that J.P.F. was the real author.

J.P.F. also transmitted to Ethel the teachings of a group of advanced spirits, who explained the meanings of the paintings. These teachings were collected in 1933 in the richly illustrated book “A Goodly Company,” that Ethel self-published under the imprint The Chiswick Press. They have a distinguished Theosophical flavor, although it is difficult to connect them to any particular orthodoxy or organization.

Of the forty-four paintings created by Ethel, or— she would have insisted—by the spirit, twenty-one were donated in 1968, two years before the artist died at age 96 in 1970, to the College of Psychic Studies, and have been on display there ever since. The Horse Hospital in London offered their first public exhibition in 2014. Other materials by Ethel Le Rossignol occasionally surface in public auctions, but her production was quite limited and they remain extremely scarce.

There is currently an international interest in spirit painters and other artists who claimed to be guided by supernatural beings, and academics such as Marco Pasi have devoted several articles to the most distinguished of them, including Hilma af Klint and Georgiana Houghton (1814–1884).

While Houghton and af Klint painted in a non-figurative style, Le Rossignol is best seen as an example of the didactic art illustrating Theosophical and esoteric ideas epitomized by Reginald Machell (1854–1927) in the early years of modern Theosophy. Le Rossignol’s style, which includes an Oriental touch, is however unique and original. She certainly deserves to be better known.

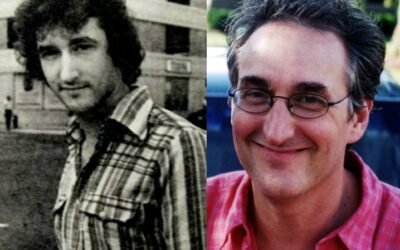

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.