With the renowned New Jersey artist, art made by Christian Scientists came of age. It took Christian Science principles into all realms of modern artistic production.

by Massimo Introvigne

Mary Baker Eddy (1821–1910), the founder of Christian Science, one of the “old” American new religions (not to be confused with the more recent Scientology), taught that “Divine Science, rising above physical theories, excludes matter, resolves things into thoughts, and replaces the objects of material sense with spiritual ideas.” “The crude creations of mortal thought must finally give place to the glorious forms, which we sometimes behold in the camera of divine Mind, when the mental picture is spiritual and eternal. Mortals must look beyond fading, finite forms, if they would gain the true sense of things” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” 1910 ed., 123 and 263–64).

Eddy understood that these ideas might have immediate applications in the visual arts. She wrote that, “The artist is not in his painting. The picture is the artist’s thought objectified.” She put these words in the mouth of an idealized Christian Science artist: “I have spiritual ideals, indestructible and glorious. When others see them as I do, in their true light and loveliness,—and know that these ideals are real and eternal because drawn from Truth,—they will find that nothing is lost, and all is won, by a right estimate of what is real” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” 1910 ed., 310 and 359–60).

Translating these principles into an aesthetic was neither easy nor unanimous. Eddy herself favored, at first, a didactic art in which artists were mobilized to illustrate books she and her church published.

But what about an art inspired by Christian Science principles but not directly illustrating its textbooks? This was a challenge for a subsequent generation of artists. Born in Jersey City, New Jersey, in 1874, into a family of artists, Violet Oakley (1874–1961) started in 1900 a process that led to her conversion to Christian Science. She was a member of her Christian Science church in Philadelphia for sixty years, where she also served as one of the two readers (i.e., lay ministers conducting the service).

Along with Jesse Willcox Smith (1863–1935) and Elizabeth Shippen Green (1871–1954), Oakley was one of the three “Red Rose Girls.” All were well-off socialites and pupils of the renowned Swedeborgian illustrator Howard Pyle (1853–1911). The three young women chose to live together in Philadelphia’s Red Rose Inn from 1899 to 1901, aiming to carve out a place in a profession dominated by men.

Oakley became the first American woman to obtain a public mural commission. The forty-three murals in Harrisburg’s Pennsylvania State Capitol, created between 1902 and 1927, are considered a masterpiece of American muralism and resulted in numerous other commissions.

We read in a monograph about Oakley and the murals that “her firm Christian Science beliefs strongly influenced her life and work” and that art was for her “a way to teach moral values that would elevate the human spirit.” “Sometimes her wholehearted devotion [to Christian Science] was refreshing, but some of her associates resented her proselytizing lectures” (Pennsylvania Capitol Preservation Committee, “A Sacred Challenge: Violet Oakley and the Pennsylvania Capitol Murals,” Harrisburg 2002, 28).

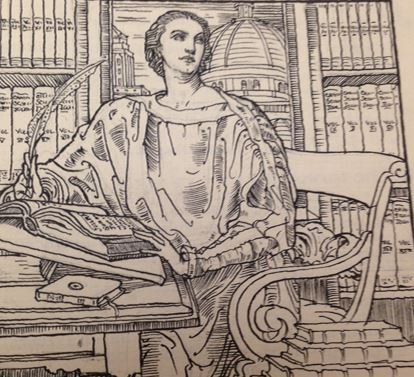

Yet, we may still ask ourselves in what sense Oakley was a Christian Science artist. She worked for Christian Science publications and painted two portraits of Eddy. She also produced a woodcut illustration of Eddy for the cover of “The Christian Science Journal.”

However, she claimed that Christian Science inspired her non-religious work as well.

Oakley considered her best work the mural “Unity,” which celebrated the end of the Civil War and slavery in the Pennsylvania Senate Chamber. It expressed, she said, “beauty and harmony and inspiration and the effect of these: Peace in the mind of the beholder.”

Some of Oakley’s murals attempt to summarize the tenets of Christian Science more explicitly. One example is “Divine Law: Love and Wisdom,” her first mural for the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. Angels carry the letters that form the words “Love and Wisdom,” while the Divine Truth, partially concealed and partially revealed, looms in the background.

During World War II, Violet Oakley crafted twenty-four portable triptychs intended for American battleships, military bases, and airfields. While they seem conventional at first glance, a closer inspection uncovers distinct Christian Science elements, such as the spirit’s victory over matter, which promises triumph and tranquility.

With Oakley, art created by Christian Scientists matured. She demonstrated that illustrating Christian Science books is not essential to conveying the principles and spirit of the religion within the evolving realm of modern art.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.